“We must make friends with the many-tentacled alien idea.”

“We must make friends with the many-tentacled alien idea.”

—John H. Lienhard, “Medicine and Maggots”

Hardly a week goes by without at least one reference to John Carpenter’s 1982 masterpiece The Thing appearing in my Facebook feed. No other film has wound its way so deeply into the collective psyche of the quirky amorphous Weird Fiction community that comprises the largest single segment of my social network. Although Carpenter’s film is essentially a science fiction film in its elements and a work of horror in its structure, a powerful consensus clearly exists that it constitutes the finest and purest exemplar of The Weird in cinema. Interestingly its closest rivals to this title, Alien (1979) and Phase IV (1974), are also science fiction/horror hybrids. This aspect of The Weird’s manifestation on the screen deserves further exploration…but not right now, not while we have other dark fissures to explore.

Carpenter’s vision is indeed masterful—a potent combination of gritty claustrophobic realism and cosmic horror, fueled by unforgettable old school special effects and note perfect editing, and driven by the performances of a cast who look like they were vat-grown for their roles, all framed within a relentless stripped down story worthy of the very best noir.

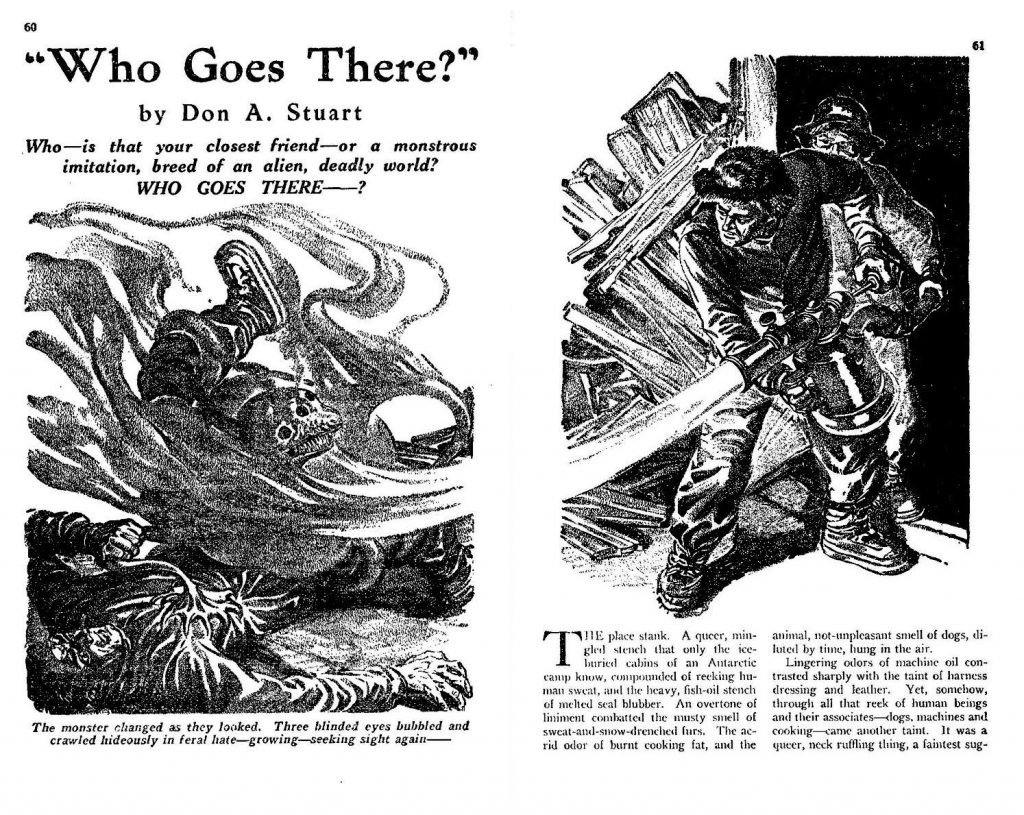

Yet Carpenter’s The Thing is actually the third of four cinematic transformations of John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella “Who Goes There?” (which Campbell originally published early in his own editorial tenure at Astounding under his sometime pseudonym Don A. Stuart). The original appearance of “Who Goes There?” on the big screen came in 1951, in Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby’s The Thing From Another World.

Yet Carpenter’s The Thing is actually the third of four cinematic transformations of John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella “Who Goes There?” (which Campbell originally published early in his own editorial tenure at Astounding under his sometime pseudonym Don A. Stuart). The original appearance of “Who Goes There?” on the big screen came in 1951, in Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby’s The Thing From Another World.

Today this early film version seems an inferior copy beside Carpenter’s take, and continues to draw criticism for its reduction of the original novella’s amorphous shape-shifting menace to an ambulatory vampiric vegetable instead. However, it remains genuinely creepy and effective, and it certainly affected me when I saw it as a child: the scene in which the Thing breaks into the base and the crew attack it with fire while Margaret Sheridan hides behind a mattress propped against the wall gave me one of my first recurring nightmares. The 1951 incarnation of The Thing may be an inferior copy, but it still contains a substantial dose of the original story’s DNA.

Campbell’s tale next manifested on the screen in an almost unrecognizable form—the 1972 film Horror Express, which reset the story as a period piece aboard the Trans-Siberian Express c. 1906. Though the creature in this heavily Hammer-influenced version begins as a frozen anthropomorph, it ultimately manifests as a psychic shapeshifter, an essentially non-corporeal entity with the ability to absorb the memories and personality of its victims—and to mimic them. Thus despite massive differences, a key element of Campbell’s take is restored. Horror Express is another favorite of my youth. I can still remember the surprise and pleasure my father and I shared at its unusually dark and unexpected twists.

Campbell’s tale next manifested on the screen in an almost unrecognizable form—the 1972 film Horror Express, which reset the story as a period piece aboard the Trans-Siberian Express c. 1906. Though the creature in this heavily Hammer-influenced version begins as a frozen anthropomorph, it ultimately manifests as a psychic shapeshifter, an essentially non-corporeal entity with the ability to absorb the memories and personality of its victims—and to mimic them. Thus despite massive differences, a key element of Campbell’s take is restored. Horror Express is another favorite of my youth. I can still remember the surprise and pleasure my father and I shared at its unusually dark and unexpected twists.

A decade later, Carpenter’s transformation returned The Thing to its roots, emphasizing the creature’s ability to create distrust and paranoia as it slowly assimilates and imitates the crew of an isolated Antarctic outpost. Parallels to the early years of the AIDS epidemic in the United States are obvious to anyone who was young and sexually active during the ‘80s—the paranoia and suspicion, the avoidance of physical contact, the constant concern about who was with who when. This subtext is brought to the fore in the film’s brilliant and unforgettable blood test scene. I have said before that The Weird serves well as a vehicle to engage with social issues, and Carpenter provided an ideal demonstration in The Thing.

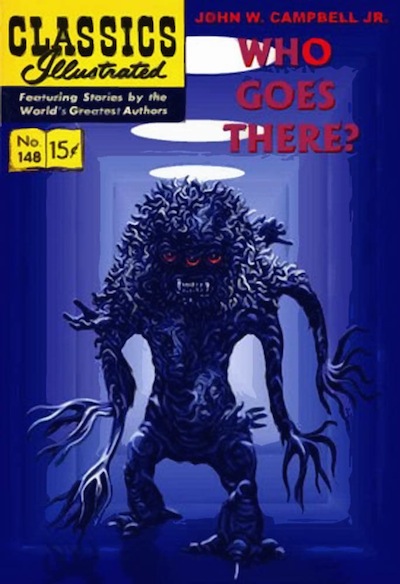

Three decades after Carpenter’s version a prequel lurched across the screen, really almost a reboot of the 1982 film, though it also revived elements of the 1951 version. In the Jan. 2010 issue of Clarkesworld, Peter Watts published a noteworthy “response” to “Who Goes There?” (and Carpenter’s film) in the tradition of Jean Rhys’ The Wide Sargasso Sea, retelling the story from the perspective of the alien and making it simultaneously more sympathetic, more tragic, and more horrific. There have also been comic book and radio adaptations, video games and action figures, along with countless parodies. Campbell’s vision, mostly in the form it took from Carpenter, has become part of our cultural psyche. The Thing has spread almost as widely as Blair feared, if not as quickly. Considering the way Hollywood currently operates, how long will it be before The Thing returns to the screen once more in yet another form? There is a saying that each generation has its Romeo and Juliet. Perhaps each generation will have its Thing as well. [My partner in the Stories From the Borderland project, artist Michael Bukowski, offers the definitive Thing for our time at his blog here:

Three decades after Carpenter’s version a prequel lurched across the screen, really almost a reboot of the 1982 film, though it also revived elements of the 1951 version. In the Jan. 2010 issue of Clarkesworld, Peter Watts published a noteworthy “response” to “Who Goes There?” (and Carpenter’s film) in the tradition of Jean Rhys’ The Wide Sargasso Sea, retelling the story from the perspective of the alien and making it simultaneously more sympathetic, more tragic, and more horrific. There have also been comic book and radio adaptations, video games and action figures, along with countless parodies. Campbell’s vision, mostly in the form it took from Carpenter, has become part of our cultural psyche. The Thing has spread almost as widely as Blair feared, if not as quickly. Considering the way Hollywood currently operates, how long will it be before The Thing returns to the screen once more in yet another form? There is a saying that each generation has its Romeo and Juliet. Perhaps each generation will have its Thing as well. [My partner in the Stories From the Borderland project, artist Michael Bukowski, offers the definitive Thing for our time at his blog here:

I am not normally one to praise or encourage remakes, sequels, prequels, or even adaptations of literary works. I would rather the cinema leave well enough alone. The problem with the 2011 version of The Thing however, is not its lack of originality. Carpenter’s version, celebrated as a truer copy, was already a twice-removed copy of the adaptation of a written work. Nor was Campbell’s novella itself necessarily so original as most readers think.

Writers in the Western World today struggle to navigate between the Scylla of artistic originality and the Charybdis of commerciality, which demands the repetition of successful formulae. While capitulation to the commercial produces homogenization, the blind worship of originality engenders an endless vomitus of shallow gimmickry. These internal tensions did not always run so deep, however.

Consider the two most influential and iconic authors in the entire Western Canon: Homer and Shakespeare. Neither showed much concern for originality, nor did their audiences demand it. Homer rewove and retold stories already centuries old by his time. Shakespeare drew his dramatic narratives from sources readily available during the Elizabethan Renaissance, most notably Holinshed’s Chronicles (it is interesting to note that his only two plays without obvious primary sources are the two with the most supernatural elements: A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest). For Shakespeare and Homer, and for countless storytellers from traditional cultures, originality has never been the goal. They sought instead to tell a known story well.

Consider the two most influential and iconic authors in the entire Western Canon: Homer and Shakespeare. Neither showed much concern for originality, nor did their audiences demand it. Homer rewove and retold stories already centuries old by his time. Shakespeare drew his dramatic narratives from sources readily available during the Elizabethan Renaissance, most notably Holinshed’s Chronicles (it is interesting to note that his only two plays without obvious primary sources are the two with the most supernatural elements: A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest). For Shakespeare and Homer, and for countless storytellers from traditional cultures, originality has never been the goal. They sought instead to tell a known story well.

Of course Shakespeare and Homer worked in far earlier times than ours, subject to different commercial imperatives, and they worked in performative media, which serves a different set of necessities than print. Today we most often encounter their work in written form, but the Iliad, the Odyssey, and all of Shakespeare’s plays were composed for the spoken word rather than the page. They have been recast and recreated–and in Homer’s case, retranslated—by each generation since, so that the works we now know are no longer the originals, nor have they been for some time, like old master paintings retouched so many times the actual brushstrokes lie buried layers beneath the surface.

The cult of originality expanded and spread with the growth of print media. Gutenberg predated Shakespeare by more than a century, which meant the Bard would live to see many of his plays pirated multiple times in print. The commodification of the written word is largely a product of the Renaissance, but its long evolution took on new life with modern copyright laws, a point driven home to the Weird Fiction community in 2014 by accusations that True Detective showrunner Nic Pizzolatto had plagiarized Thomas Ligotti (legally, he did not plagiarize—he simply appropriated Ligotti’s ideas wholesale, which is apparent from the precise care he took never to use more than two consecutive words from the Grimscribe’s work in the passages he lifted).

The cult of originality expanded and spread with the growth of print media. Gutenberg predated Shakespeare by more than a century, which meant the Bard would live to see many of his plays pirated multiple times in print. The commodification of the written word is largely a product of the Renaissance, but its long evolution took on new life with modern copyright laws, a point driven home to the Weird Fiction community in 2014 by accusations that True Detective showrunner Nic Pizzolatto had plagiarized Thomas Ligotti (legally, he did not plagiarize—he simply appropriated Ligotti’s ideas wholesale, which is apparent from the precise care he took never to use more than two consecutive words from the Grimscribe’s work in the passages he lifted).

The intensity of this fixation on originality and influence in literature achieved an apogee (or nadir?) in 1973 with critic Harold Bloom’s ridiculous The Anxiety of Influence, in which he cast the poet as a figure locked in oedipal conflict with her/his precursors. Bloom placed Shakespeare at the pinnacle of his formulation of the Western Canon, so high that no other writer can approach regardless of the depth of his/her struggle. Despite the membrane that generally separates genre and mainstream literature, we should not underestimate the penetration of Bloom’s influence into our own understanding of literary lineages in Weird Fiction: he mentored H.P. Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi for a full decade, and it is easy to see Bloom’s ideas replicated and writ small in Joshi’s own miniature canon of The Weird, with Lovecraft instead of Shakespeare positioned at its imaginary yet unreachable apex.

Of course Bloom and Joshi’s model is that of the critic, not the artist, and many writers envision their relationship to their precursors differently. Last August, author John Langan presented an alternate model in a blog post that saw widespread sharing on social media. For Langan, those writers both living and dead with whose work his own maintains a dialogue, are not frightening father figures, but friends: “…the Lovecrafts and the Kings and the Barrons, are in fact allies. Their work is a testament of faith to the field in which I work.”

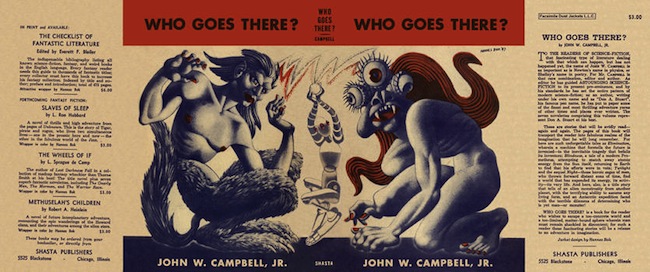

Against this background of anxiety and complexity, alliances and imitation, let us return to the presumptive original model of the Thing, John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There.” First published in the August 1938 issue of Astounding, the novella went on to become one of the most celebrated stories in all of Weird Fiction. But how “original” was Campbell’s tale? Did he work alone, or did he have allies of his own—and if he did, who were they?

Against this background of anxiety and complexity, alliances and imitation, let us return to the presumptive original model of the Thing, John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There.” First published in the August 1938 issue of Astounding, the novella went on to become one of the most celebrated stories in all of Weird Fiction. But how “original” was Campbell’s tale? Did he work alone, or did he have allies of his own—and if he did, who were they?

One obvious prototype for WGT was another novella published in Astounding just two years before Campbell’s tale and only one year before Campbell himself took over the editorship of that same magazine. H.P. Lovecraft’s “At the Mountains of Madness,” which ran as a serial in the February, March, and April 1936 issues (only a year before Lovecraft’s death) contains both shapeshifting monsters and an Antarctic setting. But Lovecraft never depicts his amoebic shoggoths as capable of assuming human form, an ability they did not acquire until four decades later with the late Michael Shea’s 1987 novella “Fat Face.”

Lovecraft in turn had his own “allies” in the creation of “At the Mountains of Madness.” Although his tale makes explicit reference to Poe’s 1838 “novel” of Antarctic horror, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, a much more obvious prototype appeared less than a year before. Weird Tales originally published “In Amundsen’s Tent,” John Martin Leahy’s tale of aliens and the Antarctic, in January 1928, then reprinted it in August 1935, just prior to the publication of Lovecraft’s novella. Despite its heavy hand with melodrama and cliché, “In Amundsen’s Tent” likely offered varying degrees of inspiration for both “At the Mountains of Madness” and “Who Goes There.” Together the three stories present a triptych of weird Antarctic horror, all published (or republished) within a tight three year window.

The shared Antarctic setting of these three tales of malevolent aliens makes their possible connections obvious. Elizabeth Leane’s excellent study “Locating the Thing: The Antarctic as Space Alien in John W. Campbell’s ‘Who Goes There‘” (Science Fiction Studies. Volume 32, Issue 2, July 2005: 225-239), explores the important role of this setting as it culminates in Campbell’s novella, going so far as to consider the Thing itself as a manifestation of the frozen continent’s protean and hostile environment.

This Antarctic setting is only a device however, one that allows access to what Leane describes as the last “isolated space” of the Twentieth Century. Though essential to Leahy, Lovecraft, and Campbell as a source of both atmosphere and plot, setting is not the focus of their stories. All three narratives are creature stories first and polar stories second, and this distraction has led to one of Campbell’s likely major “allies” being all but forgotten. He never had to “thaw” this creature out—in his time it still lay right on the surface.

This Antarctic setting is only a device however, one that allows access to what Leane describes as the last “isolated space” of the Twentieth Century. Though essential to Leahy, Lovecraft, and Campbell as a source of both atmosphere and plot, setting is not the focus of their stories. All three narratives are creature stories first and polar stories second, and this distraction has led to one of Campbell’s likely major “allies” being all but forgotten. He never had to “thaw” this creature out—in his time it still lay right on the surface.

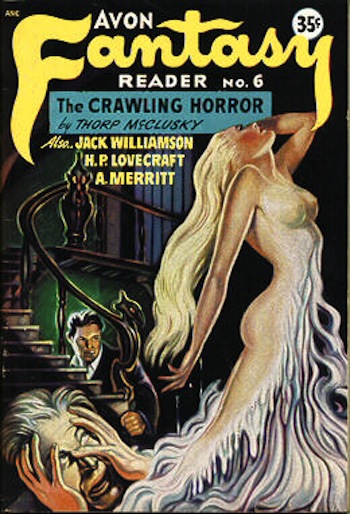

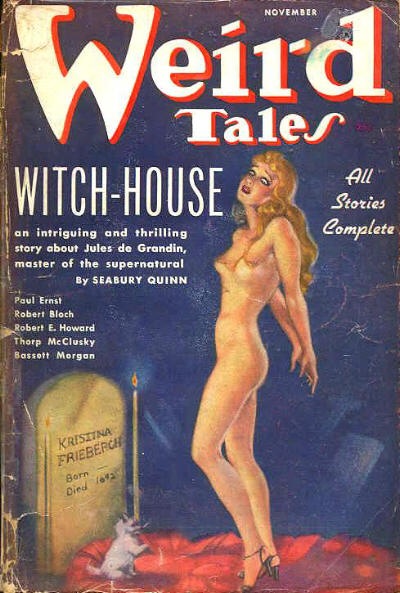

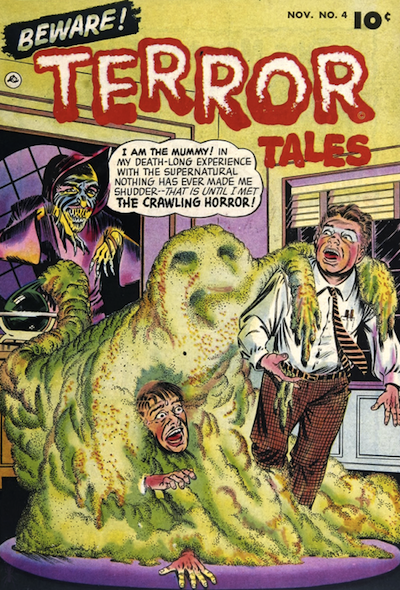

Thorp McClusky (1906-1975) published his first story, “Loot of the Vampire,” in the June 1936 issue of Weird Tales—the same month in which Robert E. Howard died. The story was a hit with readers, and with Howard gone and an ailing Lovecraft soon to follow, editor Farnsworth Wright briefly looked to McClusky as a potential new mainstay, especially after his second story, “The Crawling Horror,” in November 1936, proved just as popular as his first. It is this latter story we must watch closely.

Consider again the chronology of relevant publications within the three year window prior to the first printing of “Who Goes There,” which is the period during which John W. Campbell must have composed his tale.

|

Aug. 1935 |

In Amundsen’s Tent (reprint) |

John Martin Leahy |

Weird Tales |

|

Feb.-Apr. 1936 |

At the Mountains of Madness |

H.P. Lovecraft |

Astounding |

|

Nov. 1936 |

The Crawling Horror |

Thorp McClusky |

Weird Tales |

|

Aug. 1938 |

Who Goes There? |

Don A. Stuart, AKA John W. Campbell, Jr. |

Astounding |

Observe “The Crawling Horror” lurking hitherto unnoticed in the lineup of Campbell’s recognized influences. Is this timing just coincidence, or could “Who Goes There?” actually have absorbed some part of McClusky’s tale?

“The Crawling Horror” is no narrative of Antarctic isolation and horror. McClusky set his story in a simple rural farmhouse, the home of one Hans Ludwig Brubaker, and for a brief time, his wife Hilda. The setting is pastoral, but something is amiss even before Hilda marries Hans and takes up residence in the farmhouse. The problem unfolds as Hans shares his story with Doctor Kurt, beginning when he heard the sound of something preying on the rats in the walls.

Once all the rats are gone, something happens to Hans’ cat. And then to his dogs. Hans finally sees the creature in its primary form when it attempts to absorb one of his dogs: “…a slimy sort of stuff, transparent looking, without any shape to it.” Although he is initially able to repel the thing, it soon finishes with his dogs and moves on to his neighbors…and eventually to Hilda, leading to a You-gotta-be-fuckin’-kidding scene that remains shocking even by the standards of Carpenter’s version two generations later.

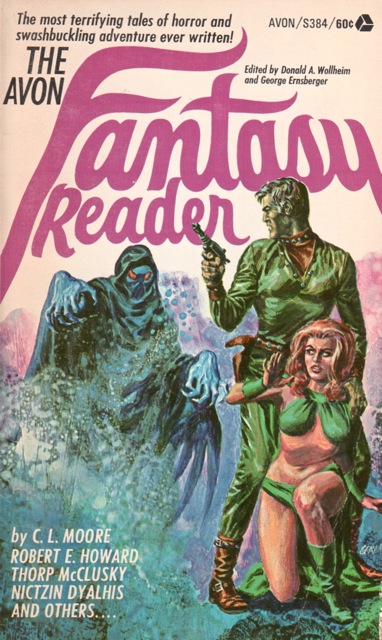

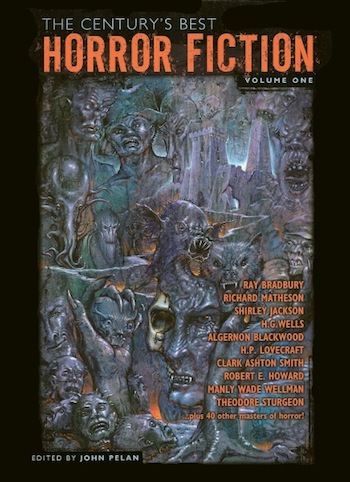

“The Crawling Horror” managed several reprints and even an Italian translation between 1948 and 1969, then languished until John Pelan revived it in the first volume of his 2012 anthology The Century’s Best Horror Fiction [and it is Pelan once again whom I must thank for bringing the tale to my attention].

“The Crawling Horror” managed several reprints and even an Italian translation between 1948 and 1969, then languished until John Pelan revived it in the first volume of his 2012 anthology The Century’s Best Horror Fiction [and it is Pelan once again whom I must thank for bringing the tale to my attention].

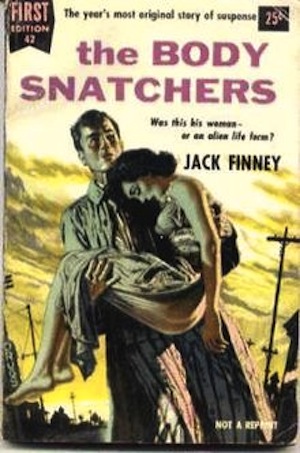

As far back as 1948, editor Donald A. Wollheim had no trouble recognizing the relationship between McClusky’s story and “Who Goes There?” in the brief introduction he gave the story in the Avon Fantasy Reader, No. 6. Wollheim however, seemed more concerned with classifying the shapeshifting creatures of both stories as some new sort of archetype rather than exploring any relationship between them. Unable to associate them with any existing creature, he proposed the label “vombis,” a term no doubt appropriated from Clark Ashton Smith’s May 1932 Weird Tales story “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis.” Yet Smith’s monsters, though squishy and boneless, are not true shapeshifters, conforming more to the trope of the mind-controlling parasites. Associating them with The Thing and the Crawling Horror seems a bit of a…stretch. Of course this lineage reappears in Robert Heinlein’s 1951 novel The Puppet Masters, which most certainly also draws on “Who Goes There?”…and from there on to Jack Finney’s 1954 novel The Body Snatchers and another cultural infestation with its own four film versions.

As Pelan points out, McClusky’s tale may even be one model for the 1958 film The Blob, which has itself spawned both a sequel and a remake, as well as 1959’s Caltiki, the Immortal Monster. The primary inspiration for the 1958 film however, likely came from Joseph Payne Brennan’s “Slime,” the topic of our very first installment of Stories From the Borderland. . The Weird’s lineage of amoebic blobs runs from the Shoggoth and McClusky’s Crawling Horror to Brennan on out through generations of film and fiction, with director Rob Zombie reported to be working on a second remake of The Blob even now.

As Pelan points out, McClusky’s tale may even be one model for the 1958 film The Blob, which has itself spawned both a sequel and a remake, as well as 1959’s Caltiki, the Immortal Monster. The primary inspiration for the 1958 film however, likely came from Joseph Payne Brennan’s “Slime,” the topic of our very first installment of Stories From the Borderland. . The Weird’s lineage of amoebic blobs runs from the Shoggoth and McClusky’s Crawling Horror to Brennan on out through generations of film and fiction, with director Rob Zombie reported to be working on a second remake of The Blob even now.

Ultimately, most all stories reveal partially digested bits of other stories under a strong enough microscope, and it seems only right for Weird Fiction writers to absorb each other’s work in one way or another. Clearly, “Who Goes there?” is one of those knotenpunkte of Weird Fiction that has devoured its predecessors and spawned copies on a Shakespearean level. But what of “The Crawling Horror”? Though all but forgotten, McClusky’s eighty year old creeper may have replicated itself not only in “Who Goes There?” but “Slime” and The Blob as well. If so, it has embedded itself far more deeply in our culture than Campbell’s tale alone…and it has done so virtually right under our noses. Which story then was more successful in its viral spread? Even Blair never saw this one coming.

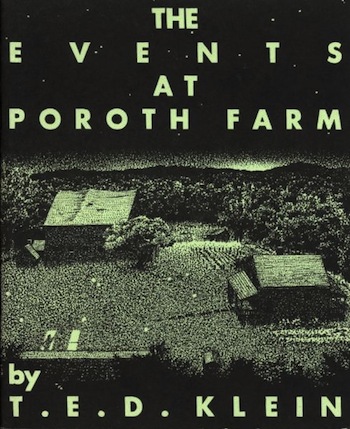

I will even suggest that “The Crawling Horror” has at least one more significant line of propagation: consider the scenario of a malevolent entity stalking an isolated farmhouse, replacing first the household cat, then the wife, and finally the husband. Does this not also describe another essential novella of Weird Fiction? Originally published in 1972 in From Beyond the Dark Gateway #2 and repeatedly revised since? Set near Flemington, NJ, barely thirty miles from my own hometown? The story that taught me that New Jersey was every bit as good a setting for Weird Fiction as New England or Antarctica?

I will even suggest that “The Crawling Horror” has at least one more significant line of propagation: consider the scenario of a malevolent entity stalking an isolated farmhouse, replacing first the household cat, then the wife, and finally the husband. Does this not also describe another essential novella of Weird Fiction? Originally published in 1972 in From Beyond the Dark Gateway #2 and repeatedly revised since? Set near Flemington, NJ, barely thirty miles from my own hometown? The story that taught me that New Jersey was every bit as good a setting for Weird Fiction as New England or Antarctica?

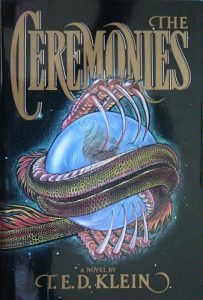

I think I can see “The Crawling Horror” peering out through the eyes of T.E.D. Klein’s “The Events at Poroth Farm,” the seminal Weird Fiction novella that provided the basis for Klein’s only novel, The Ceremonies. Each story gives me a strong déjà vu of the other, and of course “The Events at Poroth Farm” is replete with references to earlier works of Weird Fiction, each of which it echoes and internalizes. Though Klein never mentions either McClusky or his story by name, he was very much “a student of the game,” as John Pelan, would say. If anyone remembered “The Crawling Horror” in 1972, it was likely Klein.

I think I can see “The Crawling Horror” peering out through the eyes of T.E.D. Klein’s “The Events at Poroth Farm,” the seminal Weird Fiction novella that provided the basis for Klein’s only novel, The Ceremonies. Each story gives me a strong déjà vu of the other, and of course “The Events at Poroth Farm” is replete with references to earlier works of Weird Fiction, each of which it echoes and internalizes. Though Klein never mentions either McClusky or his story by name, he was very much “a student of the game,” as John Pelan, would say. If anyone remembered “The Crawling Horror” in 1972, it was likely Klein.

If this is the case, “The Crawling Horror” still survives, barely remembered yet supplying large parts of the genetic code for three of the most essential novellas in all Weird Fiction. Few still read Holinshed’s Chronicles today either, but it is with us in Shakespeare always. Though it may be the better told stories whose titles we retain, certain ideas possess a hidden life force of their own, walking among us in altered form, undying and unnoticed. Who really knows what lurks beneath the surface of our literary ecosystem? Watch the stories, and watch them close.

This is the final installment in our second series of Stories From the Borderland, and to conclude it, artist Michael Bukowski is set to infect you with an illustration of the moment in “The Crawling Horror” right before things get really disgusting here.

This is the final installment in our second series of Stories From the Borderland, and to conclude it, artist Michael Bukowski is set to infect you with an illustration of the moment in “The Crawling Horror” right before things get really disgusting here.

Stories From the Borderland may be finished for now, but if you’re following our efforts, you need not despair. Michael and I will be back with five new episodes starting in June, kicking off with a story by an author who only published two stories, both in Weird Tales. One was a decent but fairly conventional ghost story, but the other—the one Michael and I plan to showcase, is one of the great weird plant stories—and Michael and I both love weird plant stories. As always, if you can guess the title of the story in advance, you might win a prize. That prize might be a signed book, or it might be that Michael and I will allow you retain your original identity for a few months once we have assimilated the rest of the planet. Who knows? We might even keep you around for a pet.