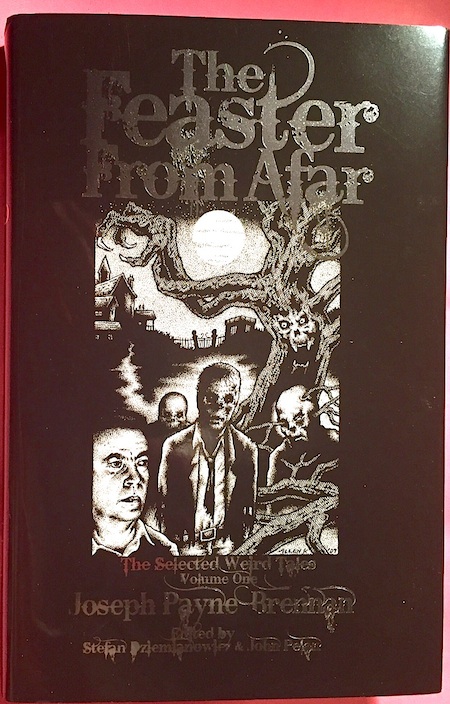

Who remembers Joseph Payne Brennan? Some of you I am sure, though not nearly as many as his work deserves. He merits a position in the lineages of Weird Horror analogous to those of David Goodis, Chester Himes, Jim Thompson, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Charles Willeford in Noir—a major practitioner of the form who arose in its postwar Silver Age. Stephen King remembers him, and has paid him homage in stories such as “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” and “The Raft.” Thomas Ligotti remembers him, and it becomes apparent in his verse—Brennan was perhaps the finest poet Weird Fiction ever had—yes, better for the most part than even Clark Ashton Smith, who had a tin ear (though “The Hashish Eater” is a masterpiece, no argument there).

Who remembers Joseph Payne Brennan? Some of you I am sure, though not nearly as many as his work deserves. He merits a position in the lineages of Weird Horror analogous to those of David Goodis, Chester Himes, Jim Thompson, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Charles Willeford in Noir—a major practitioner of the form who arose in its postwar Silver Age. Stephen King remembers him, and has paid him homage in stories such as “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” and “The Raft.” Thomas Ligotti remembers him, and it becomes apparent in his verse—Brennan was perhaps the finest poet Weird Fiction ever had—yes, better for the most part than even Clark Ashton Smith, who had a tin ear (though “The Hashish Eater” is a masterpiece, no argument there).

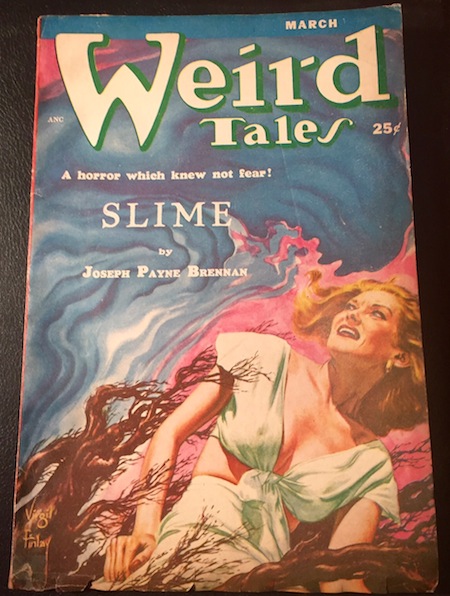

“Slime” was Brennan’s most successful tale. It began as the Weird Tales cover story for March 1953, with an interior illustration by that legend, Virgil Finlay. Time was “Slime” saw dozens of reprints in several tongues. After Brennan’s death however, that flow slowed to a trickle, then all but stopped. There are, it would appear, issues with his estate. Given his experience with Hollywood, this becomes understandable.

It was in one of these many reprint appearances that I first encountered “Slime” back in mid school, c. 1975. As soon as I began reading I knew I had found the origin of The Blob. There were differences, yes: the Slime came from the deep sea while the Blob came from Space, the Slime was black whereas the Blob was purple and red. But I was correct, though I would have to wait 30 some years or more before the courts and the Internet would confirm my intuition.

The Blob was already a particular obsession for me by then, in no small part due to a particularly frustrating habit my parents had in my childhood of letting me watch the first half hour of a movie then sending me to bed. For several years I knew nothing of what happened with the Blob after it ate the doctor. That first partial viewing immediately inspired a genuine night terror in which a “Wizzer”—a bulbous battery-powered toy top I owned at the time—transformed into the Blob and attacked me. One afternoon soon after I came home to find the house open but empty, my mother and my baby brother gone. Ignorant of Occam’s Razor, I concluded the Blob—or a blob at least—had come down our house’s faux chimney and eaten half my family. I sat crying before the open front door, a piece of scrap lumber cradled in my lap, waiting for the amoebic monster to attempt its escape, determined to die while exacting revenge. I explained my suicide mission to several confused neighbors before my mom reappeared down the street with little Todd in tow. They had gone to visit a neighbor and uncharacteristically left the door unlocked.

By the time I read “Slime” however, I had seen The Blob through to its end several times. I was obsessed with monsters as a kid, an interest that has never completely faded. And the monster in Slime, like the Blob, was a genuine monster: a true singularity.

By the time I read “Slime” however, I had seen The Blob through to its end several times. I was obsessed with monsters as a kid, an interest that has never completely faded. And the monster in Slime, like the Blob, was a genuine monster: a true singularity.

We know many monsters in the world of Horror and the Weird, but the purest are those that exist alone and outside the constraints of our natural laws. They are not born, they do not die, they have no peers, they do not reproduce: Frankenstein’s creation, King Kong, Cthulhu, Godzilla, the Blob…the creature in “Slime.” Each of these entities is isolate, a monad, unique. And in their uniqueness they hark back to the origin of the very word, for a monster is an omen, a sign, something shown, often a harbinger. Shakespeare preserves the term in its original state in his Julius Caesar, when Cassius explains a series of terrifying phenomena to Casca:

Why, you shall find

That heaven hath infused them with these spirits,

To make them instruments of fear and warning

Unto some monstrous state.

(1.3.68-71)

The original monsters were prodigious births: two-headed snakes, five-legged calves, deformed human babies, mutated exemplars of both wild beasts and domestic stock. The manifestation of such a creature was a sign of imbalance in the natural order, the revelation of some terrible rupture in the hidden warp and weft of the underlying pattern, a warning of death, destruction, the fall of houses, the collapse of regimes. Godzilla in particular is thus a nearly perfect monster in every sense. Yet while Brennan never makes of his monster the primum mobile of a cautionary tale, this dark thing vomited up from the ocean’s depths is essentially and elegantly unique:

“It had been formed when the earth and the seas were young; it was almost as old as the ocean itself. It moved through a night which had no beginning and no dissolution. The black sea basin where it lurked had been dark since the world began—and environment only a little less inimical than the stupendous gulfs of interplanetary space.”

That my friends, is a monster. It owes something no doubt to Lovecraft’s shoggoths, but while the shoggoths have intellect and seethe with ephemeral limbs and eyes, Brennan’s monster is far more refined: it has no features, no set form, and knows only hunger. And what are shoggoths after all? Former black slaves who have destroyed the “Great Race” and now rush about passages explicitly compared to the New York City subway tunnels. The creature in “Slime” has no such racist baggage any more than it has a shape. It is elemental hunger, primal horror. It is monster.

And because Stories From the Borderland is a collaborative project with artist Michael Bukowski, you can see the monster from “Slime” on his blog, yog-blogsoth. Visit both our blogs again on Dec. 9, when we showcase another great Weird story that was once widely anthologized but disappeared even more completely after its author’s death. This tale is one of the greatest Weird stories featuring children…a topic regarding which I feel I may claim some small knowledge.