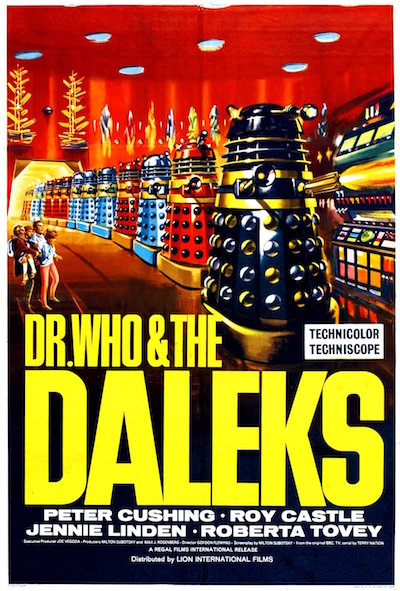

A horde of conical, unstoppable, and seemingly indestructible antagonists, exterminating all organic life with mysterious heat rays, resisting every attempt at communication and impervious to all conventional weapons everywhere but a single vulnerable point…this is a familiar scenario to most of my readers, n’est-ce pas? Only I am not describing the Daleks. My subject is les Xipéhuz. The Daleks have been around for a long time—they were born the same year as me—but the Xipéhuz have been among us a good deal longer.

J.-H. Rosny’s novella “Les Xipéhuz” first appeared in 1887, as part of the collection L’Immolation, followed less than a year later by a standalone edition of Les Xipéhuz that corrected various errors in the original. Both editions came from the French publishing house of Albert Savine, soon to achieve first notoriety then bankruptcy in rapid order after publishing both the original French translation of [then scandalous] Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and a whole series of anti-Semitic titles, the latter so rabid—even during the days of the Dreyfus Affair—as to incur the crippling fines behind the demise of the press. Sadly, J.-H. Rosny aîné seems to have shared at least some degree of his original publisher’s toxic prejudice, though unlike his British counterpart, H.G. Wells, he rarely gave voice to it, either in his work or his public persona.1 Just as Rosny moved on to a new publishing house, Mercure de France, let us make note for now and move on to the story itself.

First however, we must address the somewhat complex and confusing identity of this story’s author. I shall do my best, but if you find the thread difficult to follow, fret not: I have been reading “Rosny” for thirty years and still can’t keep this part straight.

So…the author of “Les Xipéhuz” was either J.-H. Rosny or J.-H. Rosny aîné. Both are noms de plume. J.-H. Rosny aîné was Joseph Henri Honoré Boex (1856-1940), while J.-H. Rosny was Joseph Henri Honoré Boex and his brother Séraphin Justin François Boex (1859-1948), writing together. Séraphin Justin François Boex also wrote separately as J.-H. Rosny jeune. Joseph was the older brother, hence the aîné and the jeune. Like Raymundus Joannes de Kremer (best known to us under his primary nom de plume, Jean Ray) after them, both brothers Boex were Belgian, born in Brussels (Jean Ray was born in Ghent/Gand, coincidentally in 1887, the year “Les Xipéhuz” first appeared in print). Est-ce que c’est clair, à présent? Bien.

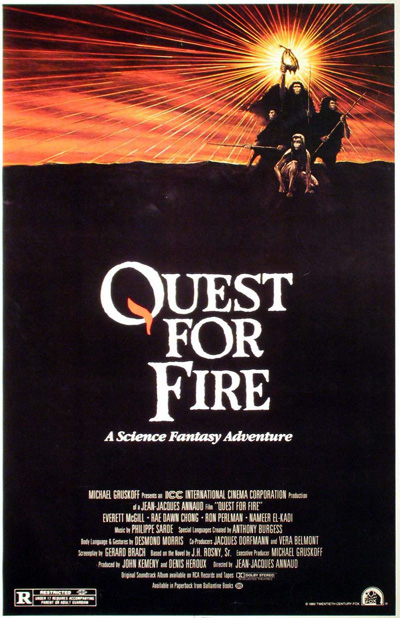

Despite the Convention Littéraire de 1935, which definitively attributes the various parts of the collective Rosny oeuvre to one brother or the other, or both, some confusion persists as to which tales are the work of J.-H. Rosny and which belong to J.-H. Rosny aîné alone. According to the Convention, the elder Boex wrote both “Les Xipéhuz” and Rosny’s best remembered work, La Guerre de Feu, the prehistoric adventure novel brought to the big screen in 1981 as Quest for Fire (arguably the best caveman movie of all time and notable as the first film to give major exposure to both Ron Perlman and Rae Dawn Chong).

Despite the Convention Littéraire de 1935, which definitively attributes the various parts of the collective Rosny oeuvre to one brother or the other, or both, some confusion persists as to which tales are the work of J.-H. Rosny and which belong to J.-H. Rosny aîné alone. According to the Convention, the elder Boex wrote both “Les Xipéhuz” and Rosny’s best remembered work, La Guerre de Feu, the prehistoric adventure novel brought to the big screen in 1981 as Quest for Fire (arguably the best caveman movie of all time and notable as the first film to give major exposure to both Ron Perlman and Rae Dawn Chong).

J.-H. Rosny occupies a position of historical importance in the genesis of francophone science fiction second only to that of Jules Verne, and corresponding in English to that of the aforementioned H.G. Wells. Though the appellation “science fiction” had yet to gain currency in either tradition when Rosny and Wells began publishing, both lived long enough to see their work absorbed into it. Dans le monde francophone, science fiction cohabits a genre ecosystem with both fantasy and a third stream, the fantastique, which remains absent from the Anglosphere as a discrete category, et c’est dans la littérature fantastique that we find much of what we recognize today as The Weird, including Jean Ray, who definitely read his fellow Belgian and found some inspiration chez Rosny.2 Though today both the French and English traditions catalogue “Les Xipéhuz” as science fiction and even recognize it as one of the genre’s foundational texts, we shall consider it equally as an exemplar of the Weird Tale.

George Slusser’s second translation, with Danièle Chatelain, appeared in this book published by Wesleyan Press in 2012.

I am not going to define the Weird Tale, Weird Fiction, or The Weird. Let us all agree that we know The Weird when we see it—comme la pornographie, n’est-ce pas? And I know I see it in “Les Xipéhuz,” more than ever after my recent experience (re)translating it into English.

If others have not viewed the story through the lens of The Weird before, it’s no real surprise. Although “Les Xipéhuz” has seen approximately half a dozen renderings into English over the past fifty years (I say approximately because George Slusser published two versions, the second translation done with Danièle Chatelain),3 previous translators seem primarily to have interested themselves in the story’s position as an important precursor of modern science fiction. It features one of the first depictions of a truly “alien” race, and in the character “Bakhoûn,” an early model for the sort of “rational” protagonist that became a hallmark of Anglophone science fiction in its later Campbellian form. Unfortunately, none of the prior English translations capture either the genuine weirdness and cosmic horror that pervade much of the story, or the almost sublime lyrical quality that Rosny’s prose achieves at its best, especially in the story’s opening sections and all its weirdest and darkest parts. Consider the tale’s opening passage, right before humanity’s first encounter with the Xipéhuz:

“Yet a full thousand years remained before that great gathering of humanity which gave rise to the civilizations of Nineveh, Babylon, and Ecbatan.

The nomadic Pjehou tribe was crossing the hostile Kzour Forest with its donkeys, horses, and cattle, heading edge on into the slanting rays of the setting sun. The song of the sunset swelled and hovered, its harmonies swirling in eddies.

Everyone was exhausted and all were silent as the tribe sought a peaceful clearing where they could light the sacred fire, prepare their evening meals, and take shelter from the elements behind a double rampart of scarlet hearths.

Opalescent clouds fled like phantom landscapes toward the four corners of the horizon, the spirits of the night played their lullaby, and still the tribe trudged on. An advance scout returned at a gallop with news of a clearing watered by a pristine spring.”4

This passage strikes me as a beautiful example of the qualities Italo Calvino defined exactly one century later as Lightness (Leggerezza) and Quickness (Rapidità). Contrast that sample now with this from the end of what more or less constitutes the story’s second act, right before the first appearance of Bakhoûn:

“From that day forward a sinister and mysterious story spread from tribe to tribe, passing in whispers from ear to ear beneath the great starry nights of Mesopotamia and gnawing at every heart: Humanity was doomed. The other, endlessly multiplying, in the forest, across the plains, indestructible, would devour the doomed race day after day. And this dark and fearful secret haunted their wretched brains and robbed them all of the will to fight, of the glowing optimism of a youthful race. The nomad who dreamt of these things no longer dared feel affection for the fertile pastures of his birth, gazing up instead at the fixed constellations with stricken pupils. The millennium of this infant people had arrived, the death knell of the world’s end, or perhaps, the resignation of the red man of the Indian prairies.

From this anguish the mystics created a bleak cult, a cult of death preached by pale prophets, the cult of Shadows stronger than the Stars, Shadows that came to engulf and devour the Holy Light, the resplendent fire.

Everywhere on the edges of the wilderness, one encountered the emaciated silhouettes of initiates, silent men who periodically wandered amongst the tribes, relating their awful dreams, the Twilight of the imminent great Night and the Death of the Sun.”5

Those two passages [the translation is mine in both] illustrate well the evocative quality of Rosny’s prose, emphasized by the contrast he presents between the first scene, depicting the nearly idyllic life of nomadic herders around the time of Göbekli Tepe, with the existential despair of the second scene following humanity’s violent encounter with an incomprehensible and implacable rival. And in the second passage we can see how fully this story is one of cosmic horror, of The Weird.

The Arno press edition in which “Les Xipéhuz” is paired with “La Morte de la Terre: and where I first encountered this story in the 1980s.

No one can say for sure where The Weird begins in literature, in any tongue, but for all its obvious elements of what would later become science fiction, “Les Xipéhuz” is definitely a powerful and important early example of cosmic horror and The Weird. Before Kubin. Before Machen. Before Dunsany, Blackwood, Chambers, James, or Shiel. Well before Lovecraft and Hodgson. Nor is this the only tale in Rosny’s oeuvre to include a healthy dose of cosmic horror. Equally notable is his 1910 novella “La Mort de la Terre” (“The Death of the Earth”), with which “Les Xipéhuz” is often paired in translation. Both stories depict humanity struggling against an inorganic race for dominion of the Earth.

Rosny aîné knew he was onto something unique with the Xipéhuz, and he wasn’t shy about proclaiming it: “Je suis le seul en France qui ait donné, avec Les Xipéhuz, un fantastique nouveau, c’est-à-dire en dehors de l’humanité” (“I am the only one in France who has created something fantastic and new, which is to say, something from beyond humanity”). Prior to “Les Xipéhuz,” alien races were always depicted as variations on the familiar anthropomorphic form, a laxity of imagination that still dominates major “science fiction” franchises such as Star Trek and Star Wars. We should note however that at no point does Rosny aîné even suggest an extraterrestrial origin for the Xipéhuz. They are, like so many of The Weird’s greatest creations, akin to the Cotton-eyed Joe. Where do they come from? Where do they go? We shall never know.

Brian Stableford’s translation appears in The Navigators of Space, the first of a six-book series in which he attempted to translate all of the key speculative fiction works of J.-H. Rosny aîné.

Rosny aîné’s accomplishment did not go unnoticed in his own time. Among those contemporaries who praised “Les Xipéhuz” was the popular novelist Alphonse Daudet (another anti-Semite, alas, and one of the most vocal), who compared it favorably to both de Maupassant’s “Le Horla” and Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. The controversial decadent author Rachilde (Marguerite Vallette-Eymery) was also a great admirer, declaring the tale downright Ibsenian. Physicist Jean Baptiste Perrin and mathematician Émile Borel also praised Rosny’s work–and “Les Xipéhuz” in particular—for its scientific legitimacy. Not only does that story contain the first literary depiction of non-carbon-based life, it also includes what is almost certainly the first portrayal of what we now call lasers, though that acronym would not be coined for seventy years yet. The Xipéhuz even use their “lasers” to communicate with glyph-like characters through a form of what we now call optical scanning. This is an exceptionally visionary detail on the author’s part, though I have never seen it acknowledged.

H.G. Wells published his first short stories the same year “Les Xipéhuz” appeared, his debut novel, The Time Machine, several years later. Comparisons between the two authors came frequently enough that Rosny aîné felt compelled to disavow any possibility of his work having influenced his more illustrious contemporary (whom he clearly admired): “Wells prefers beings that are essentially similar to those we know, while I readily imagine creatures or minerals, as in the Xipéhuz, or which are made of matter unlike our own, or which exist in a world governed by energies other than ours: the Ferromagnetics, which appear throughout Rosny’s “La Mort de la Terre” (“The Death of the Earth”) (1910) belong to one of these three categories.”6

The Lowell Bair-translated collection of Jean Ray’s stories including “The Shadowy Street” (Berkeley, 1965).

Rosny’s influence, and that of “Les Xipéhuz” in particular, seems more obvious in the work of his fellow Belgian fantasist, Jean Ray. One important Ray story that has never been published in English is especially noteworthy in this regard: “Les étranges études du Dr. Paukenschläger”(“The Strange Studies of Dr. Paukenschläger”). This early tale contains Ray’s first use of the term “monde intercalaire” (intercalary world), a central concept of much of his best—and weirdest—fiction. It also provides several intriguing hints as to the mysteries behind “La Ruelle Ténébreuse,” his far more famous novella about the Great Fire of Hamburg of 1842 (“The Gloomy Alley” or “The Shadowy Street” in Lowell Bair’s translation, which the VanderMeers republished in The Weird). A passage near the end of Paukenschläger seems almost a conscious echo of the scene in which Rosny first describes the Xipéhuz:

“We remain…on the small sandy mound, but a weird diaphanous world, only barely visible, is juxtaposed with ours. I see the pines through an almost perfectly transparent cone filled with some sort of violently roiling smoke. A dozen large spheres, bizarre bubbles, leap about on the marsh, and the same swirling smoke fills them.”7, 8

No story stands alone, and all texts exist as part of larger assemblages that include not only other texts and their authors, but readers and editors, publishers, artists, critics, agents, and other agents. Anyone who has read previous installments of Stories from the Borderland should be well aware of the surprisingly complex chains of inspiration that connect even the most seemingly obscure weird tale backwards, forwards, all around. As unique and unprecedented as Rosny aîné’s depiction of an intelligent yet completely “alien” life form was in its time, other elements of his narrative had very definite precedents. One deserves particular attention. Though barely remembered today, its influence spread far beyond “Les Xipéhuz.”

The recent definitive edition of “Vril, The Coming Race” by Edward Bulwer-Lytton from Wesleyan University Press (2012).

Edward Bulwer-Lytton is best remembered today as the author of The Last Days of Pompeii and the guy who first wrote both “the pen is mightier than the sword” and the infamously heavy-handed opener “It was a dark and stormy night” (some of you may incorrectly attribute the latter to Snoopy from Peanuts). Bulwer-Lytton was a prolific and popular author in his day, and the penultimate novel he published during his life, [Vril, the Power of] The Coming Race (1871), cast a broad shadow for a long time. Many accepted it as literal or at least “occult” truth, including Madame Blavatsky, Rudolf Steiner, and a whole host of Nazis. The latter, of course, have always been enamored of occult lost world nonsense (that part of Indiana Jones is legit–also, all good archaeologists really do hate Nazis).

The Coming Race describes an encounter with a physically, psychically, and technologically “superior” underground race, the Vril, whose destiny is one day to replace humanity as the dominant race on the Earth’s surface. This Darwinian notion of our potential obsolescence and eventual successor is an obvious influence on both Rosny aîné and Wells, first in “Les Xipéhuz” (1887), then in The Time Machine (1895), The War of the Worlds (1897), and “La Mort de la Terre” (1910), and some version of the mysterious “Vril force” is almost certainly operating in both the Xipéhuz “lasers” and the heat rays of Wells’ Martians.

Bulwer-Lytton’s Vril are still just “evolved” human beings, whereas the Xipéhuz are anything but. As inscrutable as the Solaris ocean or the creatures of Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X, they remain a mystery even in death, their crystalline cadavers still defying modern chemical analysis millennia later. Humanity cannot communicate with them, and Rosny aîné’s mise en scène demands the extinction of one race or the other.

Yet for all their impenetrable terror, the Xipéhuz are more awesome than frightening when we, as the Pjehou tribe, first encounter them:

“The clearing came into view, an enchanting spring winding its way between mosses and shrubs. There the nomads encountered a fantastic sight.

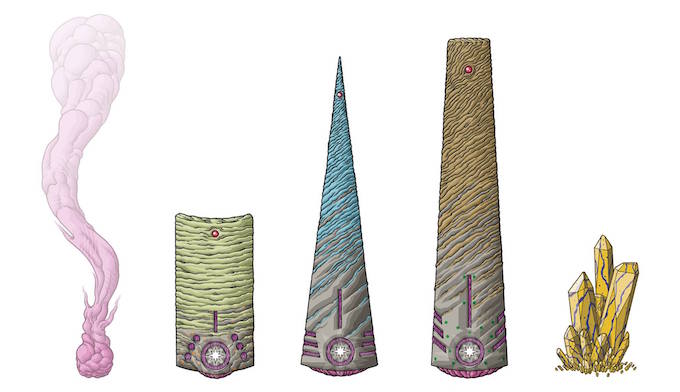

First came a great ring of translucent bluish cones with their pointed ends upright, each perhaps half the size of a man. Bright stripes and dark spirals streaked their surfaces. Each bore a star at its base, dazzling as the noonday sun.

Stranger still were the flat slabs that rose behind them, streaked with multicolored ellipses in patterns like birch bark. Here and there among these were other nearly cylindrical Shapes, one thin and tall, another low and squat, all brazen-hued and speckled with green, and all having the same characteristic point of light as the striped Shapes.”9

The excessive emphasis on Lovecraft in so much Weird Fiction scholarship has led us to associate The Weird with ugliness and grotesquerie, but its manifestation is as often a thing of terrible beauty, as in my favorite line from the Jeff VanderMeer’s Authority, when Control first sees the entrance to Area X: “He had not expected any of it to be beautiful, but it was beautiful.” Here, as well as in many of the passages where we view the Xipéhuz through Bakhoûn’s eyes, Rosny aîné shows himself adept at invoking “sensawunda,” science fiction’s contribution to the catalog of esthetic sensations that includes yugen and mono no aware. Awe, beauty, terror, wonder…all wrapped in one delicious flatbread with some roast lamb and maybe a little tzatziki sauce and rosemary…can we not recognize The Weird in this?

So humanity, meet the Xipéhuz. Their origin will ever remain a mystery, their end a tragedy, the narrative of our brief encounter with them a tale of terror, beauty, and death, the blutgeld of their genocide the inescapable heritage of our infant race, Bakhoûn’s eternal lament beneath the stars.

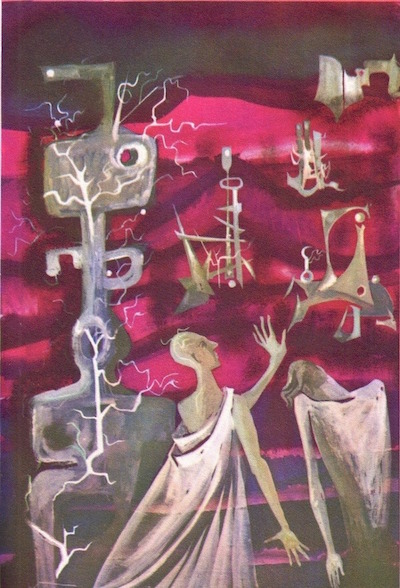

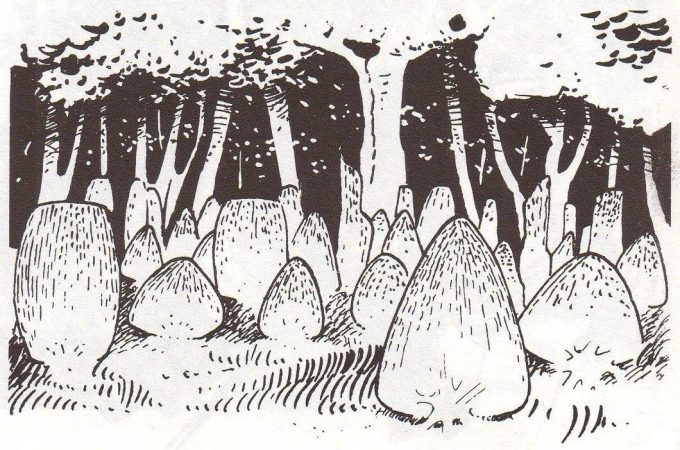

As for the obvious similarities between the Xipéhuz and the Daleks—which have not escaped French critics—these appear to be entirely coincidental. The creation of the Daleks, whether by Davros or by Terry Nation and Ray Cusick, is well established: they are the offspring of the unwholesome marriage of a pepperpot and some sort of malformed British roof architecture, their genocidal imperative derived from the Nazis themselves. I can find no evidence that Nation read French, and the first documented English translation of “Les Xipéhuz” was not published until 1968—five years after the debut of the Daleks. Perhaps he encountered the 1961 French language anthology 55 histoires extraordinaires, fantastiques et insolites edited by Marcel Aymé and Pierre-André Touttain,10 which included an extract from “Les Xipéhuz” accompanied by a very Richard Powers-esque illustration of a man, presumably Bakhoûn himself, among the Xipéhuz. Maybe that illustration caught his eye—and if he could not read the story, might he not have asked someone who could to describe it to him?

“Les Xipéhuz” was the cover illustration for the 1961 French language anthology 55 histoires extraordinaires, fantastiques et insolites edited by Marcel Aymé and Pierre-André Touttain.

The closest thing I can find to an actual smoking heat ray however, is not a full translation of “Les Xipéhuz” but an English language summary of the story published in The Theosophical Review in 1903, and credited only to “A Russian.”11 This summary actually distorts the original tale in many ways, apparently in order to bring it more in line with Theosophical dogma. At least two of these changes makes the Xipéhuz even more like the Daleks: the Russian’s version describes them as “bluish conical forms…each of a grown man’s size” (italics mine), e.g. the height of a Dalek, whereas in Rosny’s original, the Xipéhuz “never attained a height much greater than a cubit and a half” (approx. 70 cm). Even more interesting is the description of the creatures’ motion as “gliding.” These details create seven points of correspondence between the Daleks and the Xipéhuz: conical form, near-indestructability, single point of vulnerability, heat ray, height, gliding locomotion, and of course, the relentless exterminating.

In the end, we can only speculate, and whether or not the Xipéhuz provided any inspiration for the Daleks is something else we shall never know: if such a connection existed, Terry Nation took that secret to the grave. Only the Daleks themselves remain, only the Xipéhuz, only our sense of wonder…

Now follow this link to artist Michael Bukowski’s blog and see his interpretation of les Xipéhuz.

Notes:

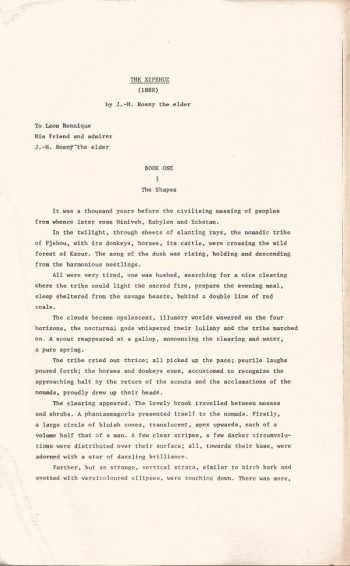

Georges T. Dodds translation (1986) with dedication toLeon Hennique, author and co-executor of Goncourt estate.

1 Brian Stableford goes on at great length in his introduction to The Navigators of Space (which includes his translation of “Les Xipéhuz”) regarding the literary conflict between the Goncourt Academy and Émile Zola—a conflict in which Rosny aîné took a very active part, but he says nothing of Rosny’s involvement in French nationalism or his stance during the Dreyfus Affair. Although the former is documented, we can only speculate as to the latter. An 1890 article from La Revue Indépendante gives a pretty good idea, however. The text of that article may be found here, but be warned: the racial “theories” Rosny aîné expresses therein approach a Lovecraftian level of offensiveness. This early statement is the only smoking gun I can find in this case, in either French or English sources, but it is more than nasty enough to make the point.

2The two authors eventually became friends, and Ray appears to have been visited the elder Rosny at home more than once. See here.

3It was in Slusser’s 1978 translation for Arno Press that I first encountered “Les Xipéhuz,” though I did not at the time realize I already knew J.-H. Rosny somewhat from Quest for Fire. See his appreciation of Rosny here.

4<< C’était mille ans avant le massement civilisateur d’où surgirent plus tard Ninive, Babylone, Ecbatane.

La tribu nomade de Pjehou, avec ses ânes, ses chevaux, son bétail, traversait la forêt farouche de Kzour, vers le crépuscule, dans la nappe des rayons obliques. Le chant du déclin s’enflait, planait, descendait des nichées harmonieuses.

Tout le monde étant très las, on se taisait, en quête d’une belle clairière où la tribu pût allumer le feu sacré, faire le repas du soir, dormir à l’abri des brutes, derrière la double rampe de brasiers rouges.

Les nues s’opalisèrent, les contrées illusoires vaguèrent aux quatre horizons, les dieux nocturnes soufflèrent le chant berceur, et la tribu marchait encore. Un éclaireur reparut au galop, annonçant la clairière et l’eau, une source pure. >>

5<< De ce jour une histoire sinistre, dissolvante, mystérieuse, alla de tribu en tribu, murmurée à l’oreille, le soir, aux larges nuits astrales de la Mésopotamie. L’homme allait périr. L’autre, toujours élargi, dans la forêt, sur les plaines, indestructible, jour par jour dévorerait la race déchue. Et la confidence, craintive et noire, hantait les pauvres cerveaux, à tous ôtait la force de lutte, le brillant optimisme des jeunes races. L’homme errant, rêvant à ces choses, n’osait plus aimer les somptueux pâturages natals, cherchait en haut, de sa prunelle accablée, l’arrêt des constellations. Ce fut l’an mil des peuples enfants, le glas de la fin du monde, ou, peut-être, la résignation de l’homme rouge des savanes indiennes.

Et, dans cette angoisse, les méditateurs venaient à un culte amer, un culte de mort que prêchaient de pâles prophètes, le culte des Ténèbres plus puissantes que les Astres, des Ténèbres qui devaient engloutir, dévorer la sainte Lumière, le feu resplendissant.

Partout, aux abords des solitudes, on rencontrait immobiles, amaigries des silhouettes d’inspirés, des hommes de silence, qui, par périodes, se répandant parmi les tribus, contaient leurs épouvantables rêves, le Crépuscule de la grande Nuit approchante, du Soleil agonisant.

6<< Wells préfère des vivants qui offrent encore une grande analogie avec ceux que nous connaissons, tandis que j’imagine volontiers des créatures ou minérales, comme dans les Xipéhuz, ou faites d’une autre matière que notre matière, ou encore existant dans un monde régi par d’autres énergies que les nôtres : les Ferromagnétaux, qui apparaissent épisodiquement dans la Mort de la Terre, appartiennent à l’une de ces trois catégories. >>

7<< Nous sommes…toujours sur le petit tertre sablonneux, mais un singulier monde diaphane, à peine visible, s’y juxtapose. Je vois le bois de sapins à travers un cône d’une transparence presque parfaite et rempli d’une sorte de fumée, violemment tourmentée. Une dizaine de grosses sphères, bulles bizarres, bondissent sur le marais, et les mêmes fumées tourbillonnantes les remplissent. >>

8Compare that passage in turn to this ominous passage from near the end of ““La Ruelle Ténébreuse”: “My grandfather and other people described how huge green flames leapt out of the wreckage all the way to the sky. They imagined they saw the faces of women of an indescribable ferocity.”

9<< La clairière apparut. La source charmante y trouait sa route entre des mousses et des arbustes. Une fantasmagorie se montra aux nomades.

C’était d’abord un grand cercle de cônes bleuâtres, translucides, la pointe en haut, chacun du volume à peu près de la moitié d’un homme. Quelques raies claires, quelques circonvolutions sombres, parsemaient leur surface; tous avaient vers la base une étoile éblouissante.

Plus loin, aussi étranges, des strates se posaient verticalement, assez semblables à de l’écorce de bouleau et madrées d’ellipses versicolores. Il y avait encore, de-ci de-là, des Formes presque cylindriques, variées d’ailleurs, les unes minces et hautes, les autres basses et trapues, toutes de couleur bronzée, pointillées de vert, toutes possédant, comme les strates, le caractéristique point de lumière. >>

10 See here.

11 See here.

Leave a Reply