Many are the reason why Great Weird stories fall into the Borderlands…

Many are the reason why Great Weird stories fall into the Borderlands…

Some because the memory of their authors faded after death, the obscurity blanketing them compounded by negligent, mismanaged, or utterly nonexistent estates. Others are lost in the shadows that skirt the ruined Tower of Babel, blocked from potential new audiences by the limited permeability between literary traditions in different tongues. Stefan Grabinski for example has only recently become known outside his own language, while Jean Ray appears to surface in English but once every decade or two, only to submerge again quickly before his full extent is ever glimpsed by le monde Anglophone…

Because it is only over the last decade or two that The Weird has truly begun to manifest as a category of its own, many of its finest flowers grew first in other gardens, awaiting only for curious herbalists to pull aside the leaves of the larger plants that cover them. Thus are the best Weird tales often harvested from the fields of science fiction, fantasy, conventional horror, and even mainstream lit.

Meanwhile the carnival barkers of the old guard, self-appointed gatekeepers of artificial micro-canons, tirelessly call attention to their bright be-tentacled tents, peddling each the same candyfloss elaborations, invariably constructed exclusively from the work of Lovecraft, his influences, his disciples, and his epigones—all the easy pickings and low hanging fruit of Weird Fiction. Readers who look beyond that gaudy bazaar of the no-longer-so-bizarre will find lost lineages, forgotten eras, entire traditions…

Of course there are those writers whose outputs were so small they never made a dent even in their own day. Some, such as Mildred Johnson (or L—– T—–, with whom we plan to conclude this series of Stories From the Borderland a few weeks from now) wrote only one or two stories.

Last are those mainstream authors who veered into The Weird perhaps only once in their careers. Patricia Highsmith was one, and her tale “The Quest for the Blank Claverengi” is one of the top three incorrect guesses for our future episodes (along with “Mimic” and “Who Goes There?”). Another was Hortense Calisher, who coincidentally shared her first name with Ms. Highsmith’s favorite pet snail. But that’s another plate o’ shrimp…

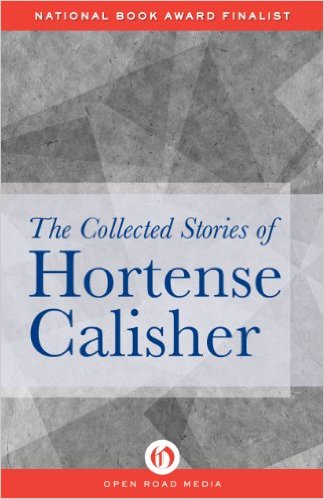

Although Hortense Calisher was 37 when she published her first story—in The New Yorker, no less—and didn’t publish her first novel until she was 50, she still managed to enjoy a robust career in American letters spanning nearly 60 years, as she continued publishing until within a few years of her death at the age of 97 in 2009.

Although Hortense Calisher was 37 when she published her first story—in The New Yorker, no less—and didn’t publish her first novel until she was 50, she still managed to enjoy a robust career in American letters spanning nearly 60 years, as she continued publishing until within a few years of her death at the age of 97 in 2009.

Hortense Calisher was an uncategorizable woman who led an uncategorizable life and an even more uncategorizable career. Though she herself is less than 10 years gone, she grew up in a household where the U.S. Civil War was living memory, which gave her what she described in her Paris Review interview (the 100th in that celebrated series) as “an inordinately stretched sense of time.” That phrase alone makes me regret she did not delve deeper into The Weird. She certainly worked otherwise with little or no regard for set formulae or boundaries. Her confident and carefully honed prose won her numerous prizes and awards, and it has kept her work fresh today, though precious little of it remains in print.

My first encounter with Calisher’s work came in the summer of 1974, when my family traveled to Washington, D.C. for a rare out-of-state vacation. Most likely we chose that location so my mother could attend some sort of teachers’ convention. While in our nation’s capital we stayed at the Hilton—rather posh for us at the time. Or perhaps we stayed across the street and only ate at the Hilton when we went to meet my mother for lunch—my memory is vague on that point.

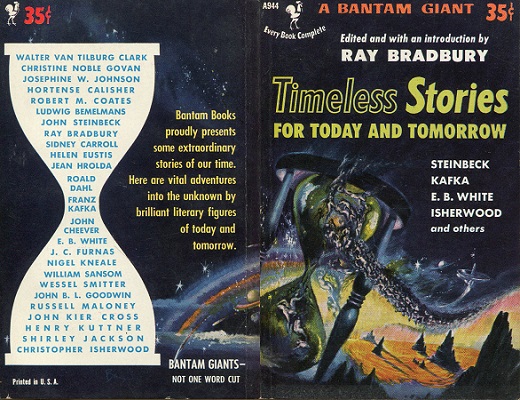

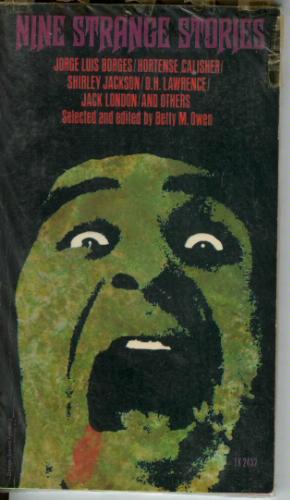

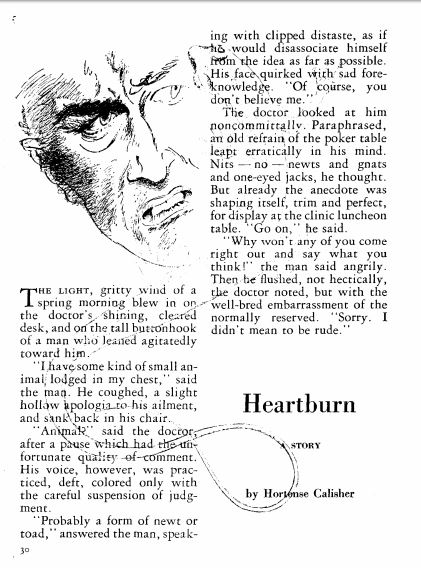

What I do recall with some certainty was finding two books alongside the obligatory Gideons’ Bible in a small drawer on the left side of the bed’s extended headboard, a kind of built-in nightstand. One was a biography of Conrad Hilton, and the other was a collection of short stories. The title of the latter book escapes me as well, but considering the year and the contents, it was most likely an edition of frequently reprinted Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow, edited by Ray Bradbury, whose multiple editions kept “Heartburn” in print for several decades. Or perhaps it was the Popular Library anthology Suddenly, which opens with Calisher’s story—which would explain why it is the only one in the book I remember reading. I would be remiss in my duties if I did not also mention its appearance (alongside Borges[!!!], Shirley Jackson, Margaret St. Clair, and the aforementioned Ms. Highsmith in Nine Strange Stories, one of the five remarkable Scholastic anthologies edited by my personal editor-hero, the late Betty M. Owen.

What I do recall with some certainty was finding two books alongside the obligatory Gideons’ Bible in a small drawer on the left side of the bed’s extended headboard, a kind of built-in nightstand. One was a biography of Conrad Hilton, and the other was a collection of short stories. The title of the latter book escapes me as well, but considering the year and the contents, it was most likely an edition of frequently reprinted Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow, edited by Ray Bradbury, whose multiple editions kept “Heartburn” in print for several decades. Or perhaps it was the Popular Library anthology Suddenly, which opens with Calisher’s story—which would explain why it is the only one in the book I remember reading. I would be remiss in my duties if I did not also mention its appearance (alongside Borges[!!!], Shirley Jackson, Margaret St. Clair, and the aforementioned Ms. Highsmith in Nine Strange Stories, one of the five remarkable Scholastic anthologies edited by my personal editor-hero, the late Betty M. Owen.

I remember reading a single story from that book our very first night in D.C., probably while my parents were unpacking and my brother and I were settling into our temporary digs, and that story stuck with me, even if its title and its author’s name did not. I was probably hooked from the second paragraph, which begins “‘I have some kind of small animal lodged in my chest,’ said the man.”

I remember reading a single story from that book our very first night in D.C., probably while my parents were unpacking and my brother and I were settling into our temporary digs, and that story stuck with me, even if its title and its author’s name did not. I was probably hooked from the second paragraph, which begins “‘I have some kind of small animal lodged in my chest,’ said the man.”

I remember the prep school boys who passed a mysterious macro-parasite from one to another like some singular affliction or curse, a sort of internal bottle imp—and how the school’s headmaster eventually came to be its host. And the solution he discovered…

Although the parasite has become a standard trope of both Weird Fiction and conventional horror, “Heartburn” is a tale with few precedents in its time. Oddly, the closet is probably “The Marmot,” a 1944 Weird Tales story by last week’s featured author, the mysterious Allison V. Harding. It is one of Harding’s few tales to be reprinted. The next major use of this trope was probably Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters (which features exo-, not endo- parasites), but that novel was not serialized until the fall of 1951, the year that “Heartburn” was first published in the January issue of The American Mercury.

“Heartburn” was one of Calisher’s earliest stories, and one of her most enduring, primarily thanks to Bradbury. I consider it a genuine classic of midcentury Weird Fiction, and that it should be remembered as such. Of all the stories the VanderMeers chose not to include in The Weird—and other than the inexplicable absence of Hodgson, it is very hard to find fault with their omissions—this may be the most perplexing, as it seems so much to their tastes. Perhaps it just never made their radar, or perhaps I misread their tastes. I however, will always love “Heartburn.” And I will always believe…

“Heartburn” was one of Calisher’s earliest stories, and one of her most enduring, primarily thanks to Bradbury. I consider it a genuine classic of midcentury Weird Fiction, and that it should be remembered as such. Of all the stories the VanderMeers chose not to include in The Weird—and other than the inexplicable absence of Hodgson, it is very hard to find fault with their omissions—this may be the most perplexing, as it seems so much to their tastes. Perhaps it just never made their radar, or perhaps I misread their tastes. I however, will always love “Heartburn.” And I will always believe…

This tale was one of the bigger challenges I have thrown Michael Bukowski in this project [at least so far—Michael, what do you think about “The Damned Thing”?], and one of the joys of working with him is the way he teases out the hidden visual hints left by authors in stories with even the most vaguely described creatures. With his illustration of le parasite from “Heartburn,” he has risen to the challenge once again here.

This tale was one of the bigger challenges I have thrown Michael Bukowski in this project [at least so far—Michael, what do you think about “The Damned Thing”?], and one of the joys of working with him is the way he teases out the hidden visual hints left by authors in stories with even the most vaguely described creatures. With his illustration of le parasite from “Heartburn,” he has risen to the challenge once again here.

“Heartburn” marks the midpoint not just for this Third Series of Stories From the Borderland, but for the project overall, at least so far as we have envisioned it at this time. Please visit us again next week when we look at a largely unrecognized classic of cosmic horror from the late 19th Century, a tale of strange shapes and forms that almost certainly provided a significant influence on certain of Jean Ray’s most important works. As always, guess the title, win a prize. X marks the spot.

“Heartburn” marks the midpoint not just for this Third Series of Stories From the Borderland, but for the project overall, at least so far as we have envisioned it at this time. Please visit us again next week when we look at a largely unrecognized classic of cosmic horror from the late 19th Century, a tale of strange shapes and forms that almost certainly provided a significant influence on certain of Jean Ray’s most important works. As always, guess the title, win a prize. X marks the spot.

Leave a Reply