This special installment first appeared as an exclusive debut for Unwinnable Monthly #84 (2016). Please visit Michael Bukowski’s blog to see his artistic interpretations of Coeurl here and Xtl here.

This special installment first appeared as an exclusive debut for Unwinnable Monthly #84 (2016). Please visit Michael Bukowski’s blog to see his artistic interpretations of Coeurl here and Xtl here.

When Michael Bukowski and I first hatched the concept for this project at NecronomiCon 2015, my working title was some clunky monstrosity along the lines of “Great Weird Stories Hidden in Plain Sight.” Fortunately Michael suggested Stories from the Borderland, the far more felicitous rubric under which our humble idea ultimately burst into the world. Never let it be said that the artist in this partnership doesn’t pull his weight on the prose side as well—something he managed more than once in this installment—whereas I am pretty much dead weight when it comes to the artistic end of things. Fortunately, Michael has that side covered.

Yet though the concept behind that original title has dwindled from sight like the oranges and sardines in Frank O’Hara’s famous poem “Why I Am Not a Painter,” it remains operative nonetheless. Stories From the Borderland was never intended as a selection of “deep cuts.” Our mission from the beginning has been to show that many of the most important stories in Weird Fiction truly are hidden in plain sight, often in other genres, especially science fiction.

In previous installments of this series, Michael and I have examined tales of cosmic horror and weirdness by such canonical science fiction authors as James Tiptree Jr., Arthur C. Clarke, J.-H. Rosny aîné and John W. Campbell. Campbell’s novella “Who Goes There” in particular—his most successful story and probably the most obvious selection we’ve tackled—has left an enormous footprint on science fiction, horror and The Weird. This time around we explore “The Black Destroyer” and “Discord in Scarlet,” a pair of closely related stories by A.E. Van Vogt whose combined impact may just be to “Who Goes There” what King Ghidorah is to Barney. The shadow of these two tales falls heavily over some of the most famous films and franchises in the speculative fiction universe. From tiny eggs, my friends…

In previous installments of this series, Michael and I have examined tales of cosmic horror and weirdness by such canonical science fiction authors as James Tiptree Jr., Arthur C. Clarke, J.-H. Rosny aîné and John W. Campbell. Campbell’s novella “Who Goes There” in particular—his most successful story and probably the most obvious selection we’ve tackled—has left an enormous footprint on science fiction, horror and The Weird. This time around we explore “The Black Destroyer” and “Discord in Scarlet,” a pair of closely related stories by A.E. Van Vogt whose combined impact may just be to “Who Goes There” what King Ghidorah is to Barney. The shadow of these two tales falls heavily over some of the most famous films and franchises in the speculative fiction universe. From tiny eggs, my friends…

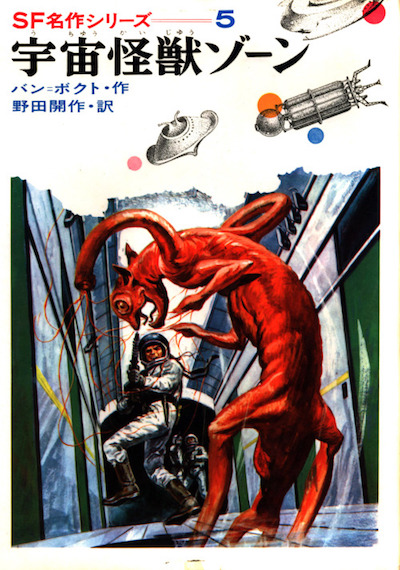

“The Black Destroyer” and “Discord in Scarlet” are essentially the same story told twice (or a second and third time perhaps, as will become clear later). In each, a highly intelligent and very hungry alien, the last of its kind, manages to make its way on board a scientific research spaceship, where it begins picking off the crew. Familiar scenario, n’est-ce pas? Yet though both stories reside at the very heart of modern science fiction, their importance to that genre is little more than historical today. Nor has Van Vogt’s prose aged well. His human characters are flat, and his fictional science is silly at best (and sinister at worst: Van Vogt was a major player in L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics, the secular operation that preceded Scientology). Both tales stand up far better as cosmic horror, thereby illustrating quite neatly the central thesis of Stories From the Borderland.

The source of the cosmic horror in each story would seem obvious: if spacemen vs. alien monster was not already a basic conflict by this time, it was well on its way. Yet Van Vogt’s monsters have a bit more depth than their human antagonists—enough that they could be considered the protagonists of their respective narratives, which are each told partly from their viewpoints. In these respects, Van Vogt’s aliens resemble Mary Shelley’s monster before them. The human crew’s struggle for survival is just…plot. The deeper, more resonant, and ultimately more horrifying stories belong to the monsters.

The source of the cosmic horror in each story would seem obvious: if spacemen vs. alien monster was not already a basic conflict by this time, it was well on its way. Yet Van Vogt’s monsters have a bit more depth than their human antagonists—enough that they could be considered the protagonists of their respective narratives, which are each told partly from their viewpoints. In these respects, Van Vogt’s aliens resemble Mary Shelley’s monster before them. The human crew’s struggle for survival is just…plot. The deeper, more resonant, and ultimately more horrifying stories belong to the monsters.

Coeurl, in “The Black Destroyer” is the last living thing on a planet decimated by nuclear war, a predator without prey. “Only too well Coeurl knew in this ultimate hour that he had missed none. There were no id-creatures left to eat. In all the hundreds of thousands of square miles that he had made his own by right of ruthless conquest…there was no id to feed the otherwise immortal engine of his body.” Coeurl’s situation is positively sunny compared to Xtl’s in “Discord is Scarlet”: “Xtl sprawled motionless on the bosom of endless night. Time dragged drearily toward infinity, and space was dark. Unutterably dark! The horrible pitch-blackness of intergalactic immensity! Across the miles and the years, vague patches of light gleamed coldly at him, whole galaxies of blazing stars shrunk by incredible distance to shining swirls of mist.” These scenarios are the true stuff of cosmic horror, of The Weird, and Coeurl and Xtl are Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” on planetary, even galactic scales: starving, immortal, alone….inhuman. Until a ship comes along…and we know this story, don’t we?

Coeurl, in “The Black Destroyer” is the last living thing on a planet decimated by nuclear war, a predator without prey. “Only too well Coeurl knew in this ultimate hour that he had missed none. There were no id-creatures left to eat. In all the hundreds of thousands of square miles that he had made his own by right of ruthless conquest…there was no id to feed the otherwise immortal engine of his body.” Coeurl’s situation is positively sunny compared to Xtl’s in “Discord is Scarlet”: “Xtl sprawled motionless on the bosom of endless night. Time dragged drearily toward infinity, and space was dark. Unutterably dark! The horrible pitch-blackness of intergalactic immensity! Across the miles and the years, vague patches of light gleamed coldly at him, whole galaxies of blazing stars shrunk by incredible distance to shining swirls of mist.” These scenarios are the true stuff of cosmic horror, of The Weird, and Coeurl and Xtl are Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” on planetary, even galactic scales: starving, immortal, alone….inhuman. Until a ship comes along…and we know this story, don’t we?

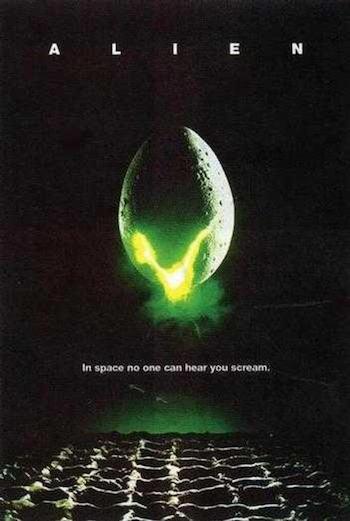

The xenomorph in the dining room for any discussion of these two Van Vogt stories is Alien. I was a junior in high school when my late father took me to see Ridley Scott’s now iconic film on its opening night, May 25, 1979. It scared the shit out of me. I loved it. And I immediately recognized the similarities between its plot and that of the 1958 film It: The Terror From Beyond Space, which also scared the shit out of me when I saw it as a kid in the Sixties on Creature Features—scared me so badly in fact that the nightmares it caused led my parents to revoke my Creature Features privileges for several years afterward, a restriction that undoubtedly delayed my later artistic development.

The xenomorph in the dining room for any discussion of these two Van Vogt stories is Alien. I was a junior in high school when my late father took me to see Ridley Scott’s now iconic film on its opening night, May 25, 1979. It scared the shit out of me. I loved it. And I immediately recognized the similarities between its plot and that of the 1958 film It: The Terror From Beyond Space, which also scared the shit out of me when I saw it as a kid in the Sixties on Creature Features—scared me so badly in fact that the nightmares it caused led my parents to revoke my Creature Features privileges for several years afterward, a restriction that undoubtedly delayed my later artistic development.

Of course I was not the only one to pick up on this resemblance between the two films, and Alien screenwriter Dan O’Bannon himself acknowledged it. Jerome Bixby, who wrote the screenplay for It: The Terror From Beyond Space, acknowledged it too. Rather than seeking redress through legal action, Bixby actually comes across in his statements on the resemblance as seeming a bit tickled by what he considered an homage, and admitted that his story in turn owed a great deal to The Thing From Another World, the original film version of “Who Goes There.” And he wasn’t the only one: Diane O’Bannon, Dan’s widow, told me “when Dan and John [Carpenter] were young friends, they both loved ‘The Thing’ and discussed what they would do with it if they ever got a chance to remake it.” You may think the chains of influence are getting complicated already, but trust me, we are only getting started.

Although Alien is not the focus of this essay, its overall importance, the franchise it spawned—and the fact that Van Vogt’s first two published stories are rarely discussed anymore without reference to it—combine to make it useful for us to think with. Let us consider for a moment what an achievement that film was, the extraordinary confluence of creative forces it represents, what a masterpiece of The Weird it remains. Together with John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of “Who Goes There?”/The Thing, Alien generally shares recognition as one of the two finest examples of cosmic horror in cinema. Both films stand up amazingly well in virtually all particulars (except perhaps for those computer displays in Alien that no longer look remotely futuristic—but then Star Wars and 2001 have the same problem). Now thanks to Diane O’Bannon we can frame them as the products of a shared aesthetic.

Although Alien is not the focus of this essay, its overall importance, the franchise it spawned—and the fact that Van Vogt’s first two published stories are rarely discussed anymore without reference to it—combine to make it useful for us to think with. Let us consider for a moment what an achievement that film was, the extraordinary confluence of creative forces it represents, what a masterpiece of The Weird it remains. Together with John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of “Who Goes There?”/The Thing, Alien generally shares recognition as one of the two finest examples of cosmic horror in cinema. Both films stand up amazingly well in virtually all particulars (except perhaps for those computer displays in Alien that no longer look remotely futuristic—but then Star Wars and 2001 have the same problem). Now thanks to Diane O’Bannon we can frame them as the products of a shared aesthetic.

Alien stands high, but it does not stand alone. No artistic creation does, and we already discussed this principle at length in regard to Shakespeare and The Thing in Stories From the Borderland #10, which is linked above. The dynamic question of Alien’s possible sources provides a springboard for the rest of this essay. When questioned about these relationships, Dan O’Bannon famously replied “I didn’t steal from anybody…I stole from everybody!” This declaration itself seems a conscious echo of T.S. Eliot’s famous statement of poetics: “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.” Young Dan O’Bannon, broke and homeless after the 1975 collapse of one of the headiest failed artistic endeavors of the last century—Jodorowsky’s Dune—was already a mature poet of cosmic horror.

Alien stands high, but it does not stand alone. No artistic creation does, and we already discussed this principle at length in regard to Shakespeare and The Thing in Stories From the Borderland #10, which is linked above. The dynamic question of Alien’s possible sources provides a springboard for the rest of this essay. When questioned about these relationships, Dan O’Bannon famously replied “I didn’t steal from anybody…I stole from everybody!” This declaration itself seems a conscious echo of T.S. Eliot’s famous statement of poetics: “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.” Young Dan O’Bannon, broke and homeless after the 1975 collapse of one of the headiest failed artistic endeavors of the last century—Jodorowsky’s Dune—was already a mature poet of cosmic horror.

The artistry of Alien rises to the level of visual poetry, and O’Bannon’s script provides the backbone of that brilliance. Drawing on a wide variety of sources, he and Ridley Scott created something that ultimately transcended them all: not only It: The Terror From Beyond Space and Mario Bava’s 1965 Terrore nello spazio (AKA Planet of the Vampires), but also the 1974 film Dark Star, his own previous outing with pre-The Thing John Carpenter, as well as multiple EC Comics tales and stories by Philip Jose Farmer and Clifford Simak. “Who Goes There”/The Thing From Another World, obviously. Also Forbidden Planet (1956). We’ll get back to Forbidden Planet…

A.E. Van Vogt’s 1939 story “Discord in Scarlet” is also frequently suggested as a source for Alien. Neither O’Bannon nor Van Vogt ever mentioned any such connection—but then they both would have signed nondisclosure agreements, because Van Vogt sued 20th Century Fox over Alien…just as Harlan Ellison supposedly did with The Terminator and Joseph Payne Brennan did over The Blob—we discussed Brennan’s case previously in this series. Whatever the details of these cases, they remain sealed by the courts. O’Bannon insisted that he had not read Van Vogt prior to his work on Alien. Diane confirms it. There we let the record stand. Considering how openly O’Bannon credited other influences, I am inclined to believe him. Van Vogt’s tales almost certainly did influence Alien, but that influence may have been entirely indirect, as we shall see.

A.E. Van Vogt’s 1939 story “Discord in Scarlet” is also frequently suggested as a source for Alien. Neither O’Bannon nor Van Vogt ever mentioned any such connection—but then they both would have signed nondisclosure agreements, because Van Vogt sued 20th Century Fox over Alien…just as Harlan Ellison supposedly did with The Terminator and Joseph Payne Brennan did over The Blob—we discussed Brennan’s case previously in this series. Whatever the details of these cases, they remain sealed by the courts. O’Bannon insisted that he had not read Van Vogt prior to his work on Alien. Diane confirms it. There we let the record stand. Considering how openly O’Bannon credited other influences, I am inclined to believe him. Van Vogt’s tales almost certainly did influence Alien, but that influence may have been entirely indirect, as we shall see.

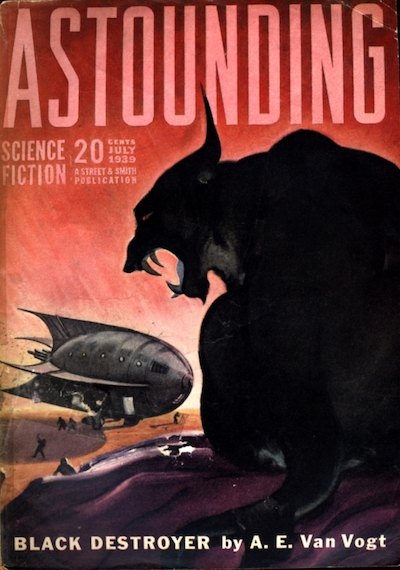

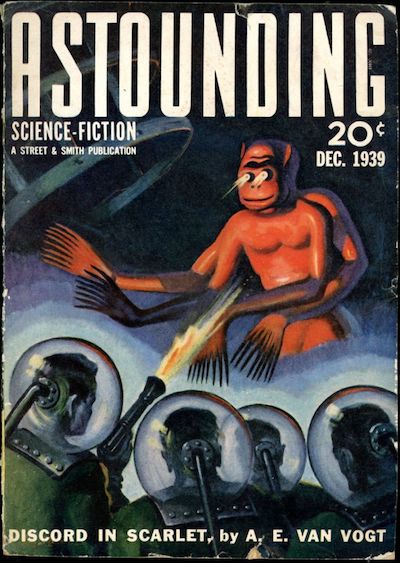

“Discord in Scarlet” first appeared in the December 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. It was Van Vogt’s second published story, following “The Black Destroyer,” his debut which made the cover of the July 1939 issue of the same magazine [we shall return to “The Black Destroyer” at greater length]. John W. Campbell had only recently taken the helm at Astounding Stories and expanded the title to Astounding Science-Fiction in March 1938. Many date the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction to that very July 1939 issue with Van Vogt’s first story. Campbell had already published “Who Goes There” in the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction under his Don A. Stuart pseudonym, and elements of that novella’s genetic code are recognizable in both of the stories under discussion here, an inspiration Van Vogt admitted. He simply transposed Campbell’s scenario of isolated scientists menaced by a highly intelligent alien from Antarctica to outer space.

“Discord in Scarlet” first appeared in the December 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. It was Van Vogt’s second published story, following “The Black Destroyer,” his debut which made the cover of the July 1939 issue of the same magazine [we shall return to “The Black Destroyer” at greater length]. John W. Campbell had only recently taken the helm at Astounding Stories and expanded the title to Astounding Science-Fiction in March 1938. Many date the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction to that very July 1939 issue with Van Vogt’s first story. Campbell had already published “Who Goes There” in the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction under his Don A. Stuart pseudonym, and elements of that novella’s genetic code are recognizable in both of the stories under discussion here, an inspiration Van Vogt admitted. He simply transposed Campbell’s scenario of isolated scientists menaced by a highly intelligent alien from Antarctica to outer space.

The alien antagonist of “Discord in Scarlet” is Xtl (Ixtl in the novel), an entity that has survived from the universe before the “Big Bang.” Astronomer/author Fred Hoyle did not coin the latter term until 1949, so it does not appear in either version of the story, but cyclic/exploding/expanding universe models had already gained traction by 1939, and Van Vogt was no doubt aware of some of these theories, so Big Bang it is. A retrofit. His story lives on so why should it not accept updates?

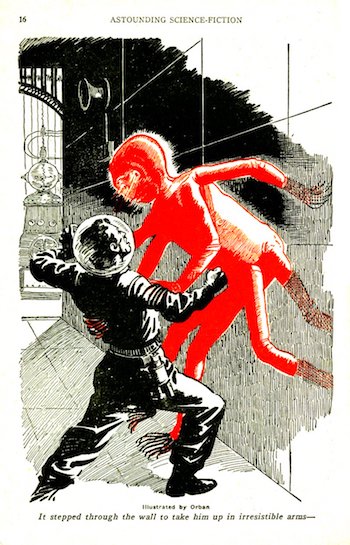

[I]Xtl is the second incredibly dangerous creature the crew allows on board their ship, and they quickly regret the repetition of their recklessness [once bitten, twice science?]. Like Coeurl in “The Black Destroyer” (we are getting to that tale, I promise!), Xtl possesses superhuman intelligence, though in both creatures this capability appears to be somewhat atrophied due to long isolation (there is perhaps an echo of Stoker’s Dracula in this, the way he is slow to recognize the full range of his abilities). Once aboard, Xtl evades the crew by traveling through the ship’s ductwork and begins abducting crewmembers to serve as hosts (guuls) for its eggs. Eventually the crew get rid of Xtl through an airlock. The parallels with the plot of Alien will be apparent. Of course, most of the same parallels occur in It: The Terror From Beyond Space as well.

[I]Xtl is the second incredibly dangerous creature the crew allows on board their ship, and they quickly regret the repetition of their recklessness [once bitten, twice science?]. Like Coeurl in “The Black Destroyer” (we are getting to that tale, I promise!), Xtl possesses superhuman intelligence, though in both creatures this capability appears to be somewhat atrophied due to long isolation (there is perhaps an echo of Stoker’s Dracula in this, the way he is slow to recognize the full range of his abilities). Once aboard, Xtl evades the crew by traveling through the ship’s ductwork and begins abducting crewmembers to serve as hosts (guuls) for its eggs. Eventually the crew get rid of Xtl through an airlock. The parallels with the plot of Alien will be apparent. Of course, most of the same parallels occur in It: The Terror From Beyond Space as well.

Since the studio settled Van Vogt’s lawsuit out of court, we can only conjecture as to any specific similarities that might have been proposed by Van Vogt and his attorney. “Discord in Scarlet” shares multiple elements with Alien. But “Discord in Scarlet” also shares multiple elements with Van Vogt’s own “The Black Destroyer.” And both stories owe an obvious debt to Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” So who draws from whom? What a web we weave.

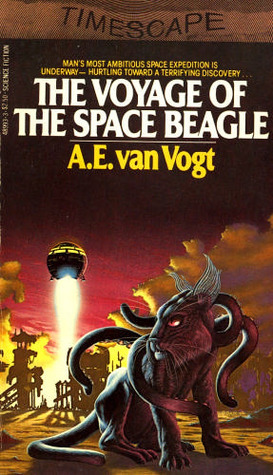

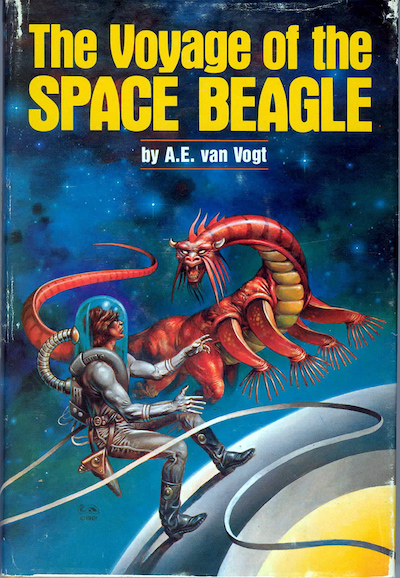

I should and shall note here that these two Van Vogt tales appeared in two distinct versions: the original stories from Astounding were later rewritten, along with two other tales, to create the 1950 “fix-up” novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle. The rewriting is rather heavy—and heavy-handed—in parts. Much of the interpolated material concerns the fictional science of “nexialism,” (which given the timing of the rewrite is probably both Van Vogt’s answer to Asimov’s “psychohistory” and a watered down version of Hubbard’s Dianetics). Unless otherwise indicated, all references herein are to the earlier publications. This pairing of “The Black Destroyer,” first through its strange meiosis into “Discord in Scarlet,” followed by the imperfect mitosis of both tales into their Space Beagle versions complicates the problem of tracing their influences even further. It becomes difficult if not impossible to determine which version of which story influenced what—often combined with Van Vogt’s own model: “Who Goes There?”

Let us examine “The Black Destroyer” more closely. Coeurl, a feline-appearing monster, tricks the crew of a research ship into taking it on board, where it can begin to feed. Coeurl’s diet is restricted to something called “id,” which it can only extract from fresh kills. Id eventually turns out to be potassium (phosphorus in the original story). Van Vogt’s repurposing of the familiar Freudian term is confusing, but not without precedent: consider Edgar Rice Burroughs’ use of helium for a city on Mars. Van Vogt must have been familiar with the Freudian denotation, as he uses “ego” in the Freudian sense only a few lines from his second reference to “id,” less than 10 paragraphs into the story. Is this just sloppiness, or was Van Vogt deliberately creating cognitive dissonance? The latter possibility frankly seems outside his toolkit, but the grave has closed on any further knowledge of his technique as well.

Let us examine “The Black Destroyer” more closely. Coeurl, a feline-appearing monster, tricks the crew of a research ship into taking it on board, where it can begin to feed. Coeurl’s diet is restricted to something called “id,” which it can only extract from fresh kills. Id eventually turns out to be potassium (phosphorus in the original story). Van Vogt’s repurposing of the familiar Freudian term is confusing, but not without precedent: consider Edgar Rice Burroughs’ use of helium for a city on Mars. Van Vogt must have been familiar with the Freudian denotation, as he uses “ego” in the Freudian sense only a few lines from his second reference to “id,” less than 10 paragraphs into the story. Is this just sloppiness, or was Van Vogt deliberately creating cognitive dissonance? The latter possibility frankly seems outside his toolkit, but the grave has closed on any further knowledge of his technique as well.

Consider some of the essential elements of this story: the all-male crew of a research ship lands on a desolate planet, where they encounter the ruins of an extinct civilization—and id creatures. Certainly we have here an inspiration for Forbidden Planet, one of the most influential and respected science fiction films of all time. It is interesting that the 1956 film restored the Freudian meaning to id, and in so doing transformed the “id creature” from prey to predator (meanwhile minimizing the special effects budget by making the monster invisible, and thereby assigning its narrative to a long and respectable lineage that includes stories by de Maupassant, Bierce, Wells, Hodgson, Jean Ray and Lovecraft).

Of course the plot of Forbidden Planet draws most heavily on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. This has never been any secret (see again our previous discussion of Campbell, Shakespeare, and the “Cult of Originality”). Isn’t it likely for a film that borrows openly from one source to pick and choose from others as well? The 1956 film in turn is a recognized influence on no less a cultural icon than Star Trek, which debuted in 1966, only 10 years later.

Of course the plot of Forbidden Planet draws most heavily on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. This has never been any secret (see again our previous discussion of Campbell, Shakespeare, and the “Cult of Originality”). Isn’t it likely for a film that borrows openly from one source to pick and choose from others as well? The 1956 film in turn is a recognized influence on no less a cultural icon than Star Trek, which debuted in 1966, only 10 years later.

If Forbidden Planet is a probable model for Star Trek, so is The Voyage of the Space Beagle. The concept of an enormous ship exploring the galaxy on a scientific mission was still a relative novelty when Gene Roddenberry was conceiving Star Trek in 1964. Van Vogt’s work probably provided influences both direct and indirect on this seminal series and the franchise it spawned.

If Forbidden Planet is a probable model for Star Trek, so is The Voyage of the Space Beagle. The concept of an enormous ship exploring the galaxy on a scientific mission was still a relative novelty when Gene Roddenberry was conceiving Star Trek in 1964. Van Vogt’s work probably provided influences both direct and indirect on this seminal series and the franchise it spawned.

Coeurl is also the likely model for Larry Niven’s Kzinti, the violent race of feline aliens he first portrayed in 1966 as part of his Known Space series. Niven attempted to introduce the Kzinti to the Star Trek universe but the cancellation of the original program came too soon and his creatures only made it to the Animated Series, Niven presumably missing out on a nice nest egg thereby. Nonetheless we have here a second connection between Van Vogt’s tales and Star Trek.

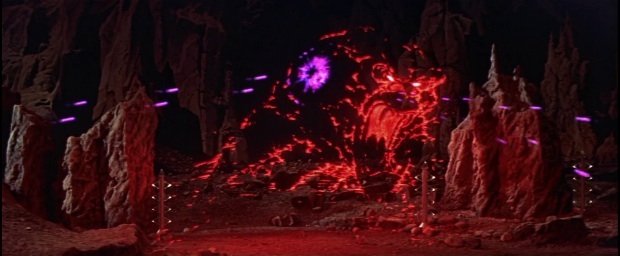

Finally, “Discord in Scarlet” and “The Black Destroyer” are also probable influences on those specific episodes of Star Trek where a monster gets loose on board the Enterprise, beginning with “The Man Trap” (1966), the very first episode of the show ever broadcast. Note that the creature in this episode subsists on salt. Sodium (Na) occupies the slot directly above Potassium (K) in the Periodic Table. Coincidences accumulate, but so does the evidence.

Finally, “Discord in Scarlet” and “The Black Destroyer” are also probable influences on those specific episodes of Star Trek where a monster gets loose on board the Enterprise, beginning with “The Man Trap” (1966), the very first episode of the show ever broadcast. Note that the creature in this episode subsists on salt. Sodium (Na) occupies the slot directly above Potassium (K) in the Periodic Table. Coincidences accumulate, but so does the evidence.

Van Vogt’s tales had thus already left their mark on screens big and small well before Alien. Direct influence on Forbidden Planet. Direct and indirect on Star Trek. It: The Terror From Beyond Space, of course. And what of Terrore nello spazio? An interesting note there: the basis for Bava’s film was a 1960 story by author Renato Pestriniero, “Una notte de 21 ore”...translated into English as “Night of the Id.” Coincidence? Pestriniero certainly knew his Van Vogt: they collaborated on a novel adapted from another of the latter’s stories.

Michael meanwhile has called my attention to a likely connection between (I)Xtl and Galactus, that venerable linchpin of the Marvel Universe. Both are survivors from the universe that preceded our own. That detail alone might seem a minor coincidence, but consider the final story cobbled into The Voyage of the Space Beagle, “M33 in Andromeda,” which features a creature called Anabis. Just like Galactus, Anabis is a devourer of worlds, especially worlds fecund with life.

Michael meanwhile has called my attention to a likely connection between (I)Xtl and Galactus, that venerable linchpin of the Marvel Universe. Both are survivors from the universe that preceded our own. That detail alone might seem a minor coincidence, but consider the final story cobbled into The Voyage of the Space Beagle, “M33 in Andromeda,” which features a creature called Anabis. Just like Galactus, Anabis is a devourer of worlds, especially worlds fecund with life.

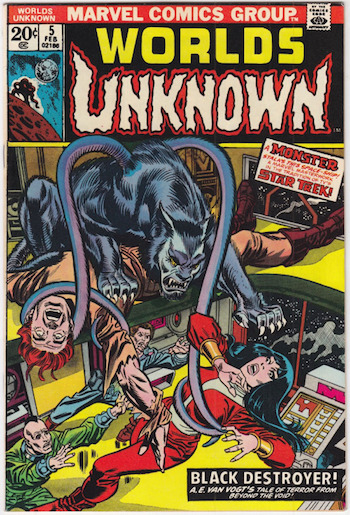

Nor is Galactus the only connection between Van Vogt’s tales and Marvel. Editor-in-chief Roy Thomas adapted “The Black Destroyer” in the February 1974 issue of Worlds Unknown. Coeurl is right there on the cover, where the tentacled feline beast has taken on a bluish tint, along with rather human facial features. Coeurl’s features and hue are almost identical to those of the then recently transformed Hank McCoy, better known to readers of Uncanny X-Men as the Beast. McCoy’s transformation into this form began in March 1972, and was also the work of Roy Thomas.

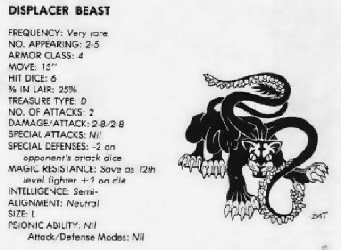

Coeurl appeared again, only a few years later, as the Displacer Beast in Dungeons & Dragons. I would have missed this one as well if it were not for Michael. This creature has been a fixture of the game since 1977, and creator Gary Gygax openly identified it as based on Coeurl. Let us note that the Displacer Beast’s tentacles bear suckers, a feature of Coeurl in the revised Voyage of the Space Beagle version only. In his original appearance those tentacles ended in hands.

Coeurl appeared again, only a few years later, as the Displacer Beast in Dungeons & Dragons. I would have missed this one as well if it were not for Michael. This creature has been a fixture of the game since 1977, and creator Gary Gygax openly identified it as based on Coeurl. Let us note that the Displacer Beast’s tentacles bear suckers, a feature of Coeurl in the revised Voyage of the Space Beagle version only. In his original appearance those tentacles ended in hands.

Dungeons and Dragons, Forbidden Planet, Star Trek, Galactus, the X-Men…Van Vogt’s stories extend their threadlike appendages in every direction. The irony is that, clumsy as Van Vogt’s stories may be, they have managed to thrive and reproduce—unlike Ixtl or Coeurl. It is far too late now to throw Van Vogt or his narratives out an airlock or abandon them in an escape pod. His monsters have spread almost everywhere. The irony is that they are now best remembered because of their alleged connection to Alien, the one place where they never laid their eggs directly.

Dungeons and Dragons, Forbidden Planet, Star Trek, Galactus, the X-Men…Van Vogt’s stories extend their threadlike appendages in every direction. The irony is that, clumsy as Van Vogt’s stories may be, they have managed to thrive and reproduce—unlike Ixtl or Coeurl. It is far too late now to throw Van Vogt or his narratives out an airlock or abandon them in an escape pod. His monsters have spread almost everywhere. The irony is that they are now best remembered because of their alleged connection to Alien, the one place where they never laid their eggs directly.

If you haven’t visited Michael Bukowski’s blog to see his artistic interpretations of Coeurl and Xtl yet, check them out here.

Stories From the Borderland is an ongoing collaboration between author Scott Nicolay and artist Michael Bukowski, presenting great stories of Weird Fiction that hover just under the radar for most contemporary readers. This special installment first appeared as an exclusive debut for Unwinnable Monthly #84 (2016). Special thanks to Diane O’Bannon for her contributions related to her late husband, screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, and to Anya Martin for editing and arranging interviews with Diane.

Stories From the Borderland is an ongoing collaboration between author Scott Nicolay and artist Michael Bukowski, presenting great stories of Weird Fiction that hover just under the radar for most contemporary readers. This special installment first appeared as an exclusive debut for Unwinnable Monthly #84 (2016). Special thanks to Diane O’Bannon for her contributions related to her late husband, screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, and to Anya Martin for editing and arranging interviews with Diane.

Leave a Reply