“don’t know if we need all this history, or the whole exquisite corpse thing—just call it ‘spontaneous collaboration’ or something?”

“don’t know if we need all this history, or the whole exquisite corpse thing—just call it ‘spontaneous collaboration’ or something?”

—Gemma Files and Stephen J. Barringer

“each thing i show you is a piece of my death”

“Many miles away something crawls to the surface…”

—The Police

“Synchronicity II”

Please visit Michael Bukowski’s blog to see his artistic interpretation here.

If you are reading this at home, please join Michael Bukowski and me in a simple collective experiment…a “spontaneous collaboration,” if you will. Walk over to your nearest bookshelf (or reach over—as long as I am in my own house, at least one bookshelf is nearly always within reach) and pick out the book on that shelf you have had the longest. How much has it aged since the first time you held it? How much have you? How much smaller in relation to your hands is it since that time? Do you remember how that book came into your possession? Was it a gift—perhaps from a former lover or a now-deceased loved one? Was it one of the first books you ever bought with your own carefully saved money—perhaps even the very first such (and if not, do you still have that first one)? Was it a special discovery you made in some funky-musty used bookstore that you visited only once during a particularly memorable and life-changing journey? Maybe you found it—in the street, in a pub, or in an empty classroom, where it sat in the corner for several weeks, unclaimed, before you finally decided it that it was better off with you and stuffed it hastily into your pack. Perhaps you stole it (exactly how many books have you stolen? Send us a letter, we won’t tell…operators are standing by).

How vivid and extensive a network of associations does that book evoke when you hold it in your hands? When you open it, do you suddenly “see some wasps caught in a sunbeam, smell cherries resting on the table”? Or do you have no idea how that book came to stand on your shelves, know only that you have had it for longer than you can clearly remember?

Now look at all the books on that particular shelf. Run your eyes over the spines and for each one ask yourself whether you remember when and where it became your own. How many associations are on that shelf? With how many people, places, events, and times are you entangled through those two or three dozen titles. How many of those connections are far removed now in space and time, how many gone forever, how many ghosts? How much sadness? How much joy? Conversely, how many books are on that shelf whose origins remain complete blanks to you, as if they leapt into existence and into your home ex nihilo?

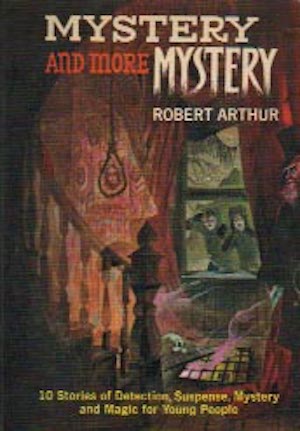

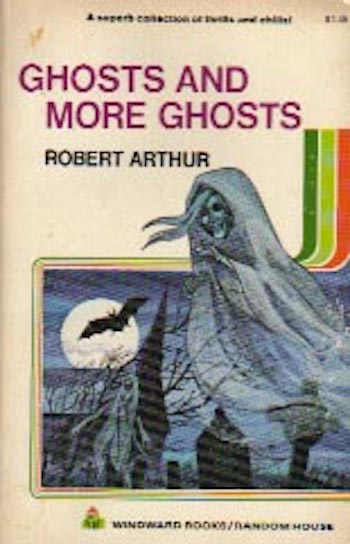

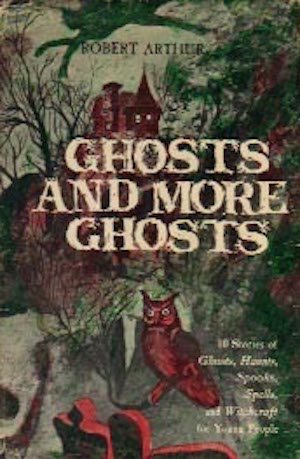

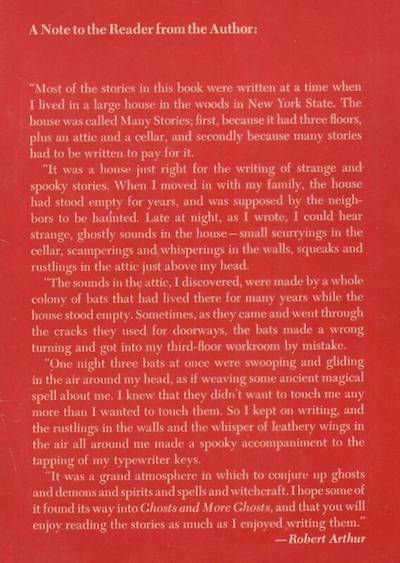

Two of the oldest books on my shelf are a matched set: The Windward Books editions of Ghosts and More Ghosts and Mystery and More Mystery, both by Robert [A.] Arthur [Jr.] (November 10, 1909 – May 2, 1969). I am certain I have had this pair of volumes since the early seventies…but I can’t say for sure where or how I acquired them. Most likely they were a gift from my parents, possibly for Christmas or my birthday.

Their publication history is somewhat confusing. These two collections of Robert Arthur’s short fiction from the pulps were published in hardcover by Random House in 1963 and 1966 respectively, and the first paperback editions from Windward Books apparently both came out in 1972. My copies only give the 1963 and 1966 dates, however, and the latter volume includes a short foreword by the author bearing a dateline of “Cape May, NJ / 1966.” Since Arthur spent the sixties in New Jersey, I almost wonder if my mother may not have met him at one of the teachers’ conventions she attended during those years in Atlantic City. Neither copy is signed however, though both bear my name inside their front covers in a neat cursive hand I have not commanded since at least 1975.

Their publication history is somewhat confusing. These two collections of Robert Arthur’s short fiction from the pulps were published in hardcover by Random House in 1963 and 1966 respectively, and the first paperback editions from Windward Books apparently both came out in 1972. My copies only give the 1963 and 1966 dates, however, and the latter volume includes a short foreword by the author bearing a dateline of “Cape May, NJ / 1966.” Since Arthur spent the sixties in New Jersey, I almost wonder if my mother may not have met him at one of the teachers’ conventions she attended during those years in Atlantic City. Neither copy is signed however, though both bear my name inside their front covers in a neat cursive hand I have not commanded since at least 1975.

Those two books just sort of appear in my memory after a certain point, probably somewhere between 1972 and 1974. I can envision—but not actually see—either of my parents simply handing them to me at some point, or leaving them unceremoniously on my bookcase or just somewhere in my room, which was a perennial mess by then. I mean a REAL mess, as in there was no traversable floor space for the better part of a decade. Anyone could have left them anywhere in my room back then and it might have been months before I found them. My mom. My dad. A ghost…

All this provides what I feel is an appropriate context for the author of the story that provides this week’s focus. Just as there are some books that seem to find their own way onto your shelves, Robert Arthur is the kind of writer whose work you may have read before you knew his name. The full scope of his career remained largely invisible during his life, like the iceberg in the familiar meme, but if you grew up reading ghost stories and mysteries anytime during the third quarter of the last century, you probably crossed his path. He was a ghost in the literary machine, a specter haunting the last century’s genre ecology.

All this provides what I feel is an appropriate context for the author of the story that provides this week’s focus. Just as there are some books that seem to find their own way onto your shelves, Robert Arthur is the kind of writer whose work you may have read before you knew his name. The full scope of his career remained largely invisible during his life, like the iceberg in the familiar meme, but if you grew up reading ghost stories and mysteries anytime during the third quarter of the last century, you probably crossed his path. He was a ghost in the literary machine, a specter haunting the last century’s genre ecology.

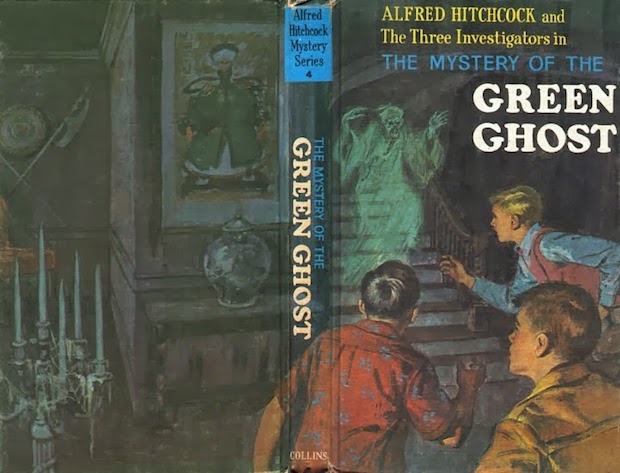

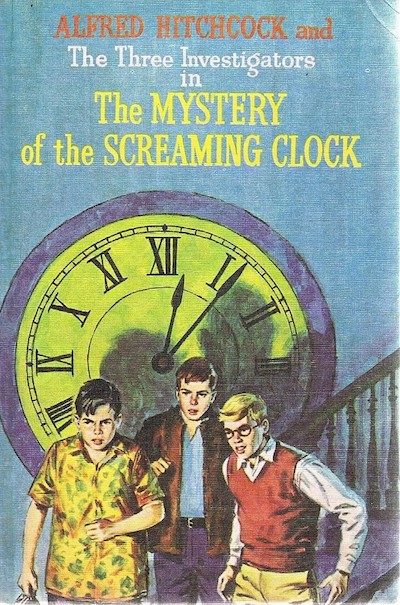

Even I read him before I knew him. Until I began the research for this essay, I did not realize that Arthur was the author of The Mystery of the Green Ghost, the fourth in the series of books about The Three Investigators (Jupiter, Peter, and Bob—not the Aqua Teen Hunger Force). Not only is this one of the first books I can remember reading, it is the first book I can remember reading multiple times—and of that I am certain. Until last week, however, I did not realize it was one of Arthur’s (I knew Arthur had written ten of the first eleven books in The Three Investigators series, but I had forgotten that book was one of them). Obviously that volume is no longer on my shelf, though I am confident I obtained it via a Scholastic book sale at school, in either First or Second Grade, so I would have read it before anything in the other two volumes. And before I read “Do You Believe in Ghosts?” AKA “The Believers.”1

We shall not explore The Three Investigators books in any depth here, as that topic is its own tangled web. Suffice it to say that Robert Arthur created the series, and that as long as he wrote them, they were all of the Weird Menace variety, in which apparently supernatural elements ultimately succumb to “rational” explanations (i.e. Scooby-Doo endings). And the first dozen or so volumes were published under the name of one Alfred Hitchcock. You may recognize that name.

We shall not explore The Three Investigators books in any depth here, as that topic is its own tangled web. Suffice it to say that Robert Arthur created the series, and that as long as he wrote them, they were all of the Weird Menace variety, in which apparently supernatural elements ultimately succumb to “rational” explanations (i.e. Scooby-Doo endings). And the first dozen or so volumes were published under the name of one Alfred Hitchcock. You may recognize that name.

Robert Arthur’s association with Hitchcock has proven a mixed blessing for his legacy, as on one hand he is best-remembered today for the books he wrote and edited under Hitchcock’s name and brand, while on the other this association has obscured his own legacy, as Arthur wrote hundreds of short stories, radio scripts, and teleplays before partnering with Hitch during what turned out to be his final decade. This partnership began through his work on Alfred Hitchcock Presents and the 1958 adaptation of his story “The Jokester” for that program. “The Jokester” originally appeared in the March 1952 edition of The Mysterious Traveler Magazine, and incorporates elements of “The Believers,” which first appeared over a decade earlier in Weird Tales, July 1941.

Robert Arthur’s association with Hitchcock has proven a mixed blessing for his legacy, as on one hand he is best-remembered today for the books he wrote and edited under Hitchcock’s name and brand, while on the other this association has obscured his own legacy, as Arthur wrote hundreds of short stories, radio scripts, and teleplays before partnering with Hitch during what turned out to be his final decade. This partnership began through his work on Alfred Hitchcock Presents and the 1958 adaptation of his story “The Jokester” for that program. “The Jokester” originally appeared in the March 1952 edition of The Mysterious Traveler Magazine, and incorporates elements of “The Believers,” which first appeared over a decade earlier in Weird Tales, July 1941.

Much more biographical and bibliographical information on Robert Arthur is now available online than one could find just a decade ago, thanks mostly to fans of The Three Investigators, and to his daughter, author Elizabeth Arthur. We will leave you to follow those breadcrumb trails on your own, but here and here are a few links to start you on your way.2

Meanwhile, let us return to “The Believers,” which I first encountered sometime in the early seventies as “Do You Believe in Ghosts?” We take you now to So-Pure Soaps Present Dare Danger with Deene! In this thrilling episode, star Nick Deene lies handcuffed to an old brass bed in the abandoned Carriday Mansion, armed only with flashlight, Bible, and crucifix, as he awaits the arrival of “the Thing with a face like an oyster,” the amorphous swamp-dwelling abomination that has carried out the Carriday Curse for over a century…except that Nick Deene just made up both Thing and Curse himself, a subject of some tension with his technical assistant, disenchanted former fan Danny Lomax. Nick Deene waits, and five million listeners across the country wait with him, glued to their radio sets, attentive to the sounds of creaking floorboards and clicking deathwatch beetles in the walls, sounds that Nick Deene actually makes himself with various devices he had hidden on his person when the two skeptical newspapermen locked his cuffs and left him to his fate.

Meanwhile, let us return to “The Believers,” which I first encountered sometime in the early seventies as “Do You Believe in Ghosts?” We take you now to So-Pure Soaps Present Dare Danger with Deene! In this thrilling episode, star Nick Deene lies handcuffed to an old brass bed in the abandoned Carriday Mansion, armed only with flashlight, Bible, and crucifix, as he awaits the arrival of “the Thing with a face like an oyster,” the amorphous swamp-dwelling abomination that has carried out the Carriday Curse for over a century…except that Nick Deene just made up both Thing and Curse himself, a subject of some tension with his technical assistant, disenchanted former fan Danny Lomax. Nick Deene waits, and five million listeners across the country wait with him, glued to their radio sets, attentive to the sounds of creaking floorboards and clicking deathwatch beetles in the walls, sounds that Nick Deene actually makes himself with various devices he had hidden on his person when the two skeptical newspapermen locked his cuffs and left him to his fate.

The story actually starts with the house, establishing it equally as character and setting. The narrative places the Carriday Mansion twenty miles from Hartford, presumably to the north, as the radio signal is transmitted from there to New York. This would set the story somewhere near the central Connecticut-Massachusetts border, possibly even in Massachusetts, not so far from such Weird locales as Matthew Bartlett’s Leeds, or the Quabbin Reservoir and H.P. Lovecraft’s Dunwich. Or real-life Pelham, where I spent several summers of my youth. Although I mostly grew up in New Jersey, home of the Great Swamp, the first swamps I ever saw were in Pelham, and most of that country north of Hartford is a similar mix of frost-gnawed granite, forest, and remnant wetlands. It has many dark places still, and Weird Fiction writers who have chosen to set their stories there have chosen well. Atmosphere is the macabre bread and butter of The Weird, and often serves a story far better than the more artificial constraints of plot.

To be sure, “The Believers” has both atmosphere and plot in plenty. Arthur lets Nick Deene himself set the scene for his readers, and then he leads the story expertly to first one false climax, then another, until its final lines offer one of the most perfect objective correlatives in Weird Fiction as denouement. That penultimate line has stuck with me for 45 years.

The central trope in this story lies somewhere at the nexus of ideas about mass hypnosis, the power of suggestion, and the ability of thought to change reality. None of these were new gimmicks even in 1941, when editor Dorothy McIlwraith first published “The Believers” in Weird Tales. We can see it as far back as 1904, in no less a cultural monument than J.M. Barrie’s original stage play Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, when Peter Pan himself breaks the fourth wall and asks all the children in the audience to clap their hands if they believe in fairies. Peter Pan, we should note, also has the ability to think things into existence.

The ultimate roots of this particular network of concepts regarding the power of faith and thought over creations and reality are far beyond our scope here; that kind of research represents at least an entire doctoral dissertation, and I already have a topic for mine. Let us note however, that just as such beliefs do not begin with Robert Arthur’s little gem of a story, they do not end there either. We find them strong in popular culture a decade later in Reverend Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 bestseller The Power of Positive Thinking. Peale’s book marks the beginning of the sort of mass-marketed hokum that still manifests today in motivational posters. The sermons he delivered from the pulpit were the soundtrack to Sunday dinners in my childhood home, and to this day I cannot think of mashed potatoes without hearing his voice…or vice versa. Nor can I deny however, that his storytelling style had as much early influence over me in that seminal period as Robert Arthur, H.P. Lovecraft, the Hardy Boys, or Peale’s fellow WOR radio personality, Jean Shepherd. I can still hear him building suspense as the man trying to rescue a baby from an old well comes to a Y as his family lowers him face-first down the rusty shaft.3

The ultimate roots of this particular network of concepts regarding the power of faith and thought over creations and reality are far beyond our scope here; that kind of research represents at least an entire doctoral dissertation, and I already have a topic for mine. Let us note however, that just as such beliefs do not begin with Robert Arthur’s little gem of a story, they do not end there either. We find them strong in popular culture a decade later in Reverend Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 bestseller The Power of Positive Thinking. Peale’s book marks the beginning of the sort of mass-marketed hokum that still manifests today in motivational posters. The sermons he delivered from the pulpit were the soundtrack to Sunday dinners in my childhood home, and to this day I cannot think of mashed potatoes without hearing his voice…or vice versa. Nor can I deny however, that his storytelling style had as much early influence over me in that seminal period as Robert Arthur, H.P. Lovecraft, the Hardy Boys, or Peale’s fellow WOR radio personality, Jean Shepherd. I can still hear him building suspense as the man trying to rescue a baby from an old well comes to a Y as his family lowers him face-first down the rusty shaft.3

Although this concept of collective thought altering reality is the theme of “The Believers,” it is not all the story has going for it. In addition to the effective atmosphere we have already discussed, it has a great monster (of course it does, or Michael and I would not have chosen it for this series, would we?). In fact, it has a swamp monster. Although such entities are almost cliché in Weird Fiction now, their lineage was still quite young in 1941. Theodore’s Sturgeon’s “It!” had only just appeared in Unknown the preceding year (Arthur actually reprinted this story in the 1967 anthology Alfred Hitchcock Presents Stories That Scared Even Me), and the earliest example of a muck man, the “Green Monkey” from H. Russell Wakefield’s story “The Red Lodge,” dates back just to 1928.4

The connection to Wakefield’s fiction takes us in a peculiar and unexpected direction, for I have seen his story “Ghost Hunt” suggested as an influence on “The Believers” (here). Although the earliest publication date the usually reliable Internet Science Fiction Database gives for Wakefield’s story is seven years later than Arthur’s, in 1948, and also in Weird Tales, other sources give its publication date as 1938, three years before “The Believers.” In that case the Weird Tales printing must have been a reprint—which would explain why it appeared simultaneously in a [pre-Robert Arthur] Alfred Hitchcock anthology, Fear and Trembling: Shivery Stories.5

The connection to Wakefield’s fiction takes us in a peculiar and unexpected direction, for I have seen his story “Ghost Hunt” suggested as an influence on “The Believers” (here). Although the earliest publication date the usually reliable Internet Science Fiction Database gives for Wakefield’s story is seven years later than Arthur’s, in 1948, and also in Weird Tales, other sources give its publication date as 1938, three years before “The Believers.” In that case the Weird Tales printing must have been a reprint—which would explain why it appeared simultaneously in a [pre-Robert Arthur] Alfred Hitchcock anthology, Fear and Trembling: Shivery Stories.5

Whatever the relationship between the two stories, “Ghost Hunt,” even though it begins with the “live radio broadcast” motif that is so central to “The Believers,” is ultimately more an exemplar of the “evil house/room that drives the occupant insane” motif, which is closely related to—and in this case paired with—the person [since the mid 20th Century this is often a psychic researcher] spends the night in a haunted house/room on a dare motif.6 That motif actually forms one component of “The Red Lodge” as well, though Wakefield brings it only to a low boil there, rather than the full roiling head it comes to in “Ghost Hunt.” It reappears in Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House. From there we see it again in both Stephen King’s novel The Shining7 and his story “1408.” Interestingly—and perhaps not coincidentally—the protagonist of “1408,” celebrity author Mike Enslin, is a near-double for Nick Deene in “The Believers.”

Let’s back up to “The Believers.”. Whatever lines we can draw between either or both of the H. Russell Wakefield stories I have mentioned and Robert Arthur’s tale, or between these and any others that are either already on the table here or yet to come, this is not a discussion of influence. Influence is the low-hanging fruit of literary criticism, and as a field of study has spawned no meaningful body of thought other than the convoluted bloviations of Harold Bloom, which have long since withered on the vine.8

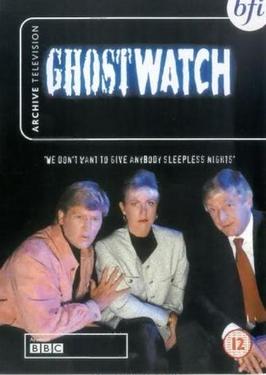

Yet one parallel to “The Believers” seems so obvious that it is practically a muck man in the drawing room (as in “The Red Lodge”). On Halloween night, 1992—almost twenty-six years ago to the hour as I type these words—BBC1 broadcast for the first and only time, a program called Ghostwatch. This extraordinarily effective and controversial bit of television, perhaps the most infamous successor to Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast (Oct. 30, 1938), still sends its ripples down through our culture, despite the small number of people who actually saw it the first time it aired.

Yet one parallel to “The Believers” seems so obvious that it is practically a muck man in the drawing room (as in “The Red Lodge”). On Halloween night, 1992—almost twenty-six years ago to the hour as I type these words—BBC1 broadcast for the first and only time, a program called Ghostwatch. This extraordinarily effective and controversial bit of television, perhaps the most infamous successor to Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast (Oct. 30, 1938), still sends its ripples down through our culture, despite the small number of people who actually saw it the first time it aired.

For instance, Ghostwatch seemed such an obvious inspiration for one of the first truly great short stories of this new millenium, “each thing i show you is a piece of my death” by Gemma Files and Stephen J. Barringer, that I reached out to Files. She confirmed that although neither she nor Barringer had seen Ghostwatch, she had “definitely heard about it.” They eventually ordered both DVDs of both Ghostwatch and The Stone Tape (1972) from the U.K. as soon as these became available, and Files described the former as “brilliant” (she also told me that she read “The Red Lodge” when she was “maybe thirteen” and that “it scared the shit out of [her].”

No clear connection exists between Ghostwatch and “The Believers” though. Stephen Volk, who wrote the script of the former, has been straightforward about his sources of inspiration, most notably The Stone Tape, penned by the great Nigel Kneale. He has not, to my knowledge, ever mentioned Robert Arthur. Nor, to my genuine astonishment, can I find even now any conjoined mention of Ghostwatch and “The Believers” online. Michael Bukowski was on that one immediately however. He called it from the first time I suggested we cover “The Believers” in an episode of Stories from the Borderland.

No clear connection exists between Ghostwatch and “The Believers” though. Stephen Volk, who wrote the script of the former, has been straightforward about his sources of inspiration, most notably The Stone Tape, penned by the great Nigel Kneale. He has not, to my knowledge, ever mentioned Robert Arthur. Nor, to my genuine astonishment, can I find even now any conjoined mention of Ghostwatch and “The Believers” online. Michael Bukowski was on that one immediately however. He called it from the first time I suggested we cover “The Believers” in an episode of Stories from the Borderland.

If we are not talking about influence here, what are we talking about? One particular approach from my current disciplinary toolkit offers some utility here. Actor-network theory or ANT, most closely associated with sociologist Bruno Latour, developed out of the discipline of science and technology studies (STS). ANT can be at once incredibly simple and endlessly complicated, but I find it a useful approach for examining complex relationships involving multiple things—and we have accumulated quite a few things in the course of this essay: stories, authors, books, magazines, radio, TV, tropes, motifs, characters, settings, audiences…and monsters. And so on… ANT offers the advantage of creating symmetry between all these things via a “flattened ontology.” In this playing field, everything is a thing, and every thing may have agency, and thus be an “actant.”

Accordingly, once we flatten the network laid out in this essay, we no longer have just connections between stories, or between authors, or authors and stories. We can now see that the various media make the stories possible through their agencies and affordances. Motifs travel from print, to radio, to television. One thing that suddenly leaps out is the fact that of all these narratives, only Ghostwatch employs the medium that is its own subject. The comparable examples are all print stories about other media. Part of the beauty of Ghostwatch is that like the great circular serpent Ouroboros deep down in the World-Sea, it flattens its own ontology. It is television about television. I just happen to have Marshall McLuhan right here…

Accordingly, once we flatten the network laid out in this essay, we no longer have just connections between stories, or between authors, or authors and stories. We can now see that the various media make the stories possible through their agencies and affordances. Motifs travel from print, to radio, to television. One thing that suddenly leaps out is the fact that of all these narratives, only Ghostwatch employs the medium that is its own subject. The comparable examples are all print stories about other media. Part of the beauty of Ghostwatch is that like the great circular serpent Ouroboros deep down in the World-Sea, it flattens its own ontology. It is television about television. I just happen to have Marshall McLuhan right here…

And if we look a little more closely, we can see that the real agent (or actant) in Ghostwatch is not the millions of viewers, as it is [with listeners] in “The Believers,” but Pipes, the ghost of the pedophile Raymond Tunstall. The viewers are simply the intermediaries via which he extends his network, becomes not one Pipes but many. And Pipes himself is possessed by the malevolent spirit of Mother Seddons, herself a fictional version of the real-life historical baby-farmer and child-killer Amelia Dyer. Ghost lurks behind ghost and reality underlies fiction. Ghostwatch is a fictional reality show about a fictionalized reality.9

The most important thing an ANT approach shows us here however, is that if we actually draw all these connections, all the lines between things—between all things, whether fictional, conceptual, or “real”—the stories themselves are only points on those lines, and what connects them are deeper relations between media and concepts. The stories are simply “mediators,” like the hosts of a television or a radio program who unwittingly become hollowed out and parasitized by the more powerful agency of monstrous agents capable of flickering in between levels of an unstable reality. Don’t believe me? Join me in another spontaneous collaboration. Turn on your TV, and start flicking channels. How far can you go before you see the Thing with a face like an oyster?

The most important thing an ANT approach shows us here however, is that if we actually draw all these connections, all the lines between things—between all things, whether fictional, conceptual, or “real”—the stories themselves are only points on those lines, and what connects them are deeper relations between media and concepts. The stories are simply “mediators,” like the hosts of a television or a radio program who unwittingly become hollowed out and parasitized by the more powerful agency of monstrous agents capable of flickering in between levels of an unstable reality. Don’t believe me? Join me in another spontaneous collaboration. Turn on your TV, and start flicking channels. How far can you go before you see the Thing with a face like an oyster?

Sometimes we think we know the origins of things. But in the end there is no end—and no beginning. Each thing is just part of a network of things, sometimes an actor, sometimes an intermediary, sometimes a mediator. Here at Stories from the Borderland, we are all about following those connections through the network from one story, one knotenpunkt, to the next. Where we will stop next? Let’s just say that our cryptozoological observations are about to take us on a night flight through a tale by one of science fiction’s most essential figures of all. As always, if you can guess the answer in advance, you might win a prize. Operators are standing by for your call!

1Although “The Believers”/”Do You Believe in Ghosts?” is our subject here, and also the tale that has stayed with me most over the intervening years, I would be severely at fault if I did not also direct the reader encountering Robert Arthur’s work for the first time here toward such fabulous and disconcerting tales as “The Stamps from El Dorado” (AKA “Postmarked for Paradise”), “The Rose Crystal Bell” (AKA “Ring Once for Death”), “Mr. Dexter’s Dragon” (AKA “The Book and the Beast”), and of course, “Obstinate Uncle Otis.” Looking back, I can detect in the latter more than a hint of another classic, John Collier’s “Thus I Refute Beelzy,” from the character similarities between the uncle in the one and the father in the other, to the final telltale shoe. Collier’s story preceded Arthur’s by less than a year, so go figure…

2However, if you find an explanation for why Arthur hated oysters so harshly, please write and let us know…

3If you would like to know just how dangerous this kind of infectious collective thought is when it gets loose in the real world and distorts reality, there is one show you can tune into right now that is far more terrifying even than Ghostwatch. Follow the name of Norman Vincent Peale down the Google rabbit hole to the list of U.S. presidents with whom he was associated…and which one attended his church as a child…

4Michael and I previously examined the lineage of muck men and swamp monsters through “It!” and “The Red Lodge” in Stories from the Borderland #8 on Margaret St. Clair and her story “Brenda.” Robert Arthur published multiple stories by St. Clair in the anthologies he edited for Alfred Hitchcock, sometimes two in the same volume.

5For a real Halloween treat, check out this 1949 radio adaptation of “Ghost Hunt” from the classic program Suspense here.

6Attention budding young scholars: Weird Fiction really needs its own Stith Thompson!

7I have suggested more than once, though perhaps not in print, that The Shining is largely a combination of The Haunting of Hill House and Oliver Onions’ “The Beckoning Fair One,” with the protagonist presented as what we can now recognize as largely a stand-in for the author and his battles with substance abuse. This is to take nothing away from King’s novel, which I consider a masterpiece of Weird Fiction nearly on a par with Jackson’s.

8We examined this topic at some length in Stories from the Borderland #10, our installment on Thorp McCluskey, “Who Goes There?”, and Shakespeare…

9This Russian nesting-doll aspect of the Ghostwatch ghosts is one other obvious parallel between the BB1 program and The Blair Witch Project. The makers of the latter have always denied any connection however.

Leave a Reply