Michael Bukowski and I began this Third Series of Stories from the Borderland with “The Cactus” by Mildred Johnson, a mysterious author with only two publication credits to her name: the first a great Weird Tale, the second a more conventional ghost story. Now we are ending with “The Inhabitant of the Pond” by Linda Thornton…another mysterious author with only two publication credits to her name: the first a great Weird Tale, the second a more conventional ghost story. Obviously Michael and I were conscious of the parallels when we chose these stories, and should the readiness with which we found two such similar examples lead you to consider what this says about the circumscribed trajectories of female authors in Weird Fiction, the flat circular nature of time, or our esthetics and intentions behind this project, then we encourage you to think with those things. Ces sont bonnes à penser.

Michael Bukowski and I began this Third Series of Stories from the Borderland with “The Cactus” by Mildred Johnson, a mysterious author with only two publication credits to her name: the first a great Weird Tale, the second a more conventional ghost story. Now we are ending with “The Inhabitant of the Pond” by Linda Thornton…another mysterious author with only two publication credits to her name: the first a great Weird Tale, the second a more conventional ghost story. Obviously Michael and I were conscious of the parallels when we chose these stories, and should the readiness with which we found two such similar examples lead you to consider what this says about the circumscribed trajectories of female authors in Weird Fiction, the flat circular nature of time, or our esthetics and intentions behind this project, then we encourage you to think with those things. Ces sont bonnes à penser.

We do not know a whole hell of a lot about Linda Thornton, but even that is more than we know about Mildred Johnson, which is essentially nothing, given the likelihood that her name itself was a pseudonym, perhaps for another, better-established writer who wrote primarily under some other name, and perhaps also in other modes and genres. We may claim with some certainty that Johnson was a woman, as I suggested in my essay on “The Cactus,” but that only narrows her identity to half the world’s literate Anglophone population c. 1950. And only maybe. The loss of original payment records from Weird Tales essentially erased any trail that might have led back to Johnson, and the death of associate editor Lamont Buchanan in 2015 has deprived us of the last living link to the magazine’s original run. In comparison, we know far more about such enigmatic Weird Tales authors as Allison V. Harding, Henry Ferris Arnold Jr., and Nictzin Dyalhis (Harding in particular has turned out to be a bottomless research K-hole, the Oak Island of Weird Fiction scholarship. See Stories from the Borderland #12).

In the case of Linda Thornton however, a direct link does survive: editor Jessica Amanda Salmonson, who published both of Thornton’s known stories. Despite some speculation that Salmonson wrote the two tales herself, she confirmed through sources close to her that Thornton is indeed a discrete person, who used what appears to be her maiden name as a nom de plume. Armed with that information and one other additional clue that Salmonson provided, I was able to track her down on social media, and…this is one sleeping dog I’m going to let lie. I will say only that Ms. “Thornton” does not appear to have any ongoing interest in Horror or Weird Fiction. It is clear there is only one book in her life now, and I will leave her to it.

In the case of Linda Thornton however, a direct link does survive: editor Jessica Amanda Salmonson, who published both of Thornton’s known stories. Despite some speculation that Salmonson wrote the two tales herself, she confirmed through sources close to her that Thornton is indeed a discrete person, who used what appears to be her maiden name as a nom de plume. Armed with that information and one other additional clue that Salmonson provided, I was able to track her down on social media, and…this is one sleeping dog I’m going to let lie. I will say only that Ms. “Thornton” does not appear to have any ongoing interest in Horror or Weird Fiction. It is clear there is only one book in her life now, and I will leave her to it.

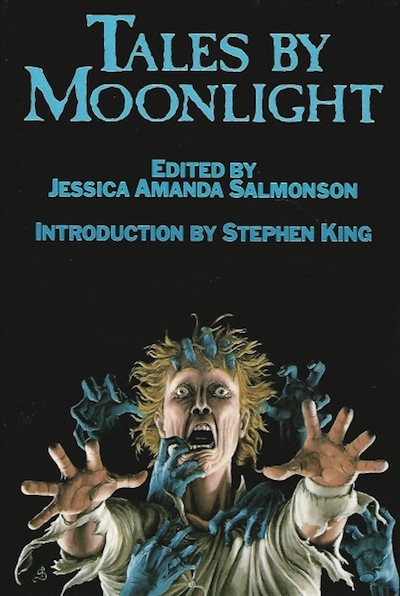

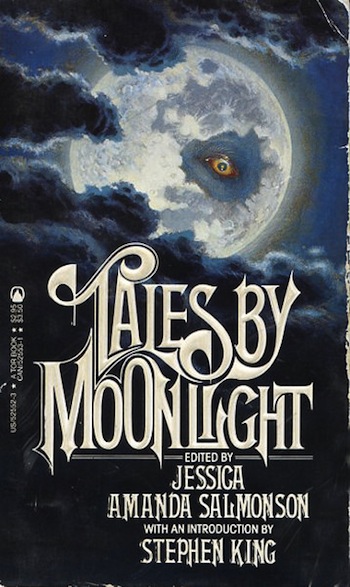

Yet things must have been a little different back in 1983, and Linda Thornton’s debut that year in Salmonson’s anthology Tales by Moonlight came with a bit of fanfare. Salmonson chose “The Inhabitant of the Pond” as the volume’s closer, and in her brief intro—in which she identifies the author only as a Texan relocated to Jamaica (the Texas part at least is true, I now know)–she exercises a rarely invoked droit de l’éditeur: “It may not be kosher for an editor to admit to having a favorite yarn in a given anthology” she says…and then she admits it anyway. I cannot recall another instance where an editor named a favorite story in a volume s/he edited. Salmonson’s editorial credibility is pretty fucking legit however, so take this as evidence of the story’s exceptionality.

As unprecedented as this praise may be, it is merely the close-bracket on an even more remarkable compliment bestowed on the story by one S. King in his introduction to Tales by Moonlight: “it’s been a long, long time since I’ve read a story as nakedly frightening as The Inhabitant of the Pond, by Linda Thornton” [italics Uncle Stevie’s or maybe the typesetter’s]. Of course, when the King’s right hand giveth two scoops, the left may taketh one away: “Ms. Thornton is not yet completely in control of her prose, and at times the note warbles. There are lapses into awkwardness…” If Paul Tremblay and Jeff VanderMeer ever read this essay–let alone King’s original intro in its entirety, in which he goes into full left-handed compliment mode and describes several of the stories in the anthology as “most exquisitely awful”–they may afterward feel even more fortunate that the kind words with which King recently anointed their work filtered only from his right hand.

As unprecedented as this praise may be, it is merely the close-bracket on an even more remarkable compliment bestowed on the story by one S. King in his introduction to Tales by Moonlight: “it’s been a long, long time since I’ve read a story as nakedly frightening as The Inhabitant of the Pond, by Linda Thornton” [italics Uncle Stevie’s or maybe the typesetter’s]. Of course, when the King’s right hand giveth two scoops, the left may taketh one away: “Ms. Thornton is not yet completely in control of her prose, and at times the note warbles. There are lapses into awkwardness…” If Paul Tremblay and Jeff VanderMeer ever read this essay–let alone King’s original intro in its entirety, in which he goes into full left-handed compliment mode and describes several of the stories in the anthology as “most exquisitely awful”–they may afterward feel even more fortunate that the kind words with which King recently anointed their work filtered only from his right hand.

It seems clear that King tempered his praise for “The Inhabitant of the Pond” out of the knowledge that Thornton was a first-time author. That story—once so fresh and exciting and filled with promise—is as old now as Dante when he wrote the Inferno, but when it was new the most successful author of our time recognized in it “a voice which is still growing in power, a strong and confident talent in the refining.” The story impressed him so much that he took it as evidence “that the genre is alive and well.”

Though Stephen King has made more than a few especially good calls in his long career, Thornton did not turn out to be another Clive Barker, alas, and despite the optimism Salmonson expressed regarding her discovery in the intro to “Mother’s Boy,” Thornton’s only other published story, the genre was left to flourish or flounder without her ongoing contributions. Perhaps those two stories were all she ever had in her. Perhaps that’s just as well. And so we are left to consider her original contribution to the field on its own—that first dark story, imperfect yet powerful, disturbing and perhaps already more than a little deranged.

Though Stephen King has made more than a few especially good calls in his long career, Thornton did not turn out to be another Clive Barker, alas, and despite the optimism Salmonson expressed regarding her discovery in the intro to “Mother’s Boy,” Thornton’s only other published story, the genre was left to flourish or flounder without her ongoing contributions. Perhaps those two stories were all she ever had in her. Perhaps that’s just as well. And so we are left to consider her original contribution to the field on its own—that first dark story, imperfect yet powerful, disturbing and perhaps already more than a little deranged.

In many ways “The Inhabitant of the Pond” is a perfect choice for Stories from the Borderland: an all but forgotten story by an all but forgotten author, prominently praised when first published but never reprinted outside a paperback version of the original limited edition hardcover collection…coupled with a cool monster for Michael to draw, the kind whose description leaves plenty of room for him to exercise his own talents. And the whole damn thing is weird as fuck. Weird as fuck and gothic as hell. Most likely Thornton was aiming for the gothic and The Weird just came along for the ride. Most likely The Weird came from somewhere deep inside.

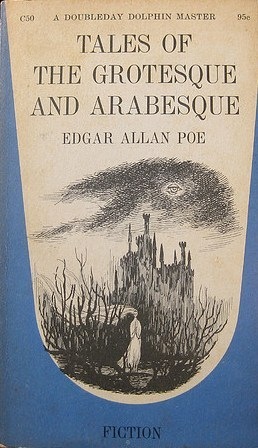

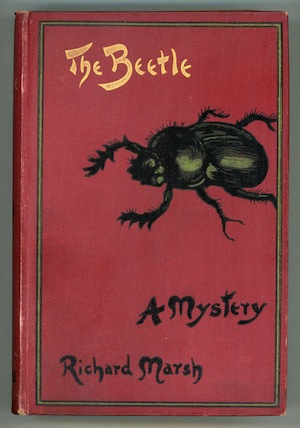

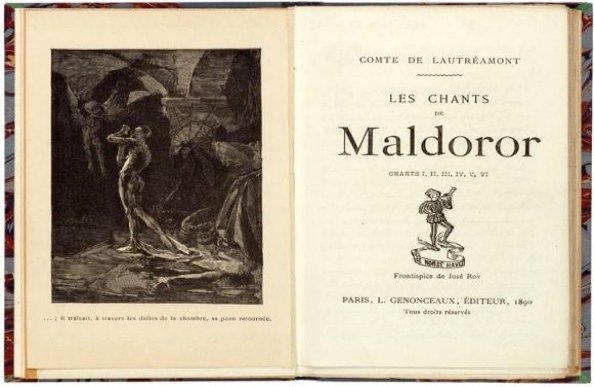

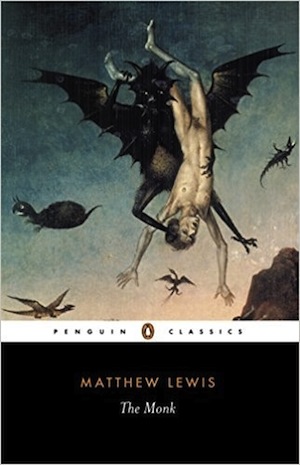

As a gothic tale from the early Eighties, “The Inhabitant in the Pond” possesses a peculiar timeless quality that was probably there from the start, and the thirty plus years since its publication have accentuated that aspect. Though Thornton’s prose is only mildly archaic for its time, the basic elements of the story hark back to nineteenth century models such as Poe and Richard Marsh. The cruel and almost transgressive brutality of the story’s climax seems at first to offer a more contemporary note—and that scene retains its freshness yet—but even this twist would not have been out of place in some of the darker gothic masterworks like Les Chants de Maldoror or The Monk. As for the story’s title, which in its possible allusion to a familiar story by Ramsey Campbell offers the only suggestion that Thornton’s reading extends into the twentieth century, I suspect editor Salmonson may have tied that final bow on the tale herself, as I know her devotion to the British author all too well.

As a gothic tale from the early Eighties, “The Inhabitant in the Pond” possesses a peculiar timeless quality that was probably there from the start, and the thirty plus years since its publication have accentuated that aspect. Though Thornton’s prose is only mildly archaic for its time, the basic elements of the story hark back to nineteenth century models such as Poe and Richard Marsh. The cruel and almost transgressive brutality of the story’s climax seems at first to offer a more contemporary note—and that scene retains its freshness yet—but even this twist would not have been out of place in some of the darker gothic masterworks like Les Chants de Maldoror or The Monk. As for the story’s title, which in its possible allusion to a familiar story by Ramsey Campbell offers the only suggestion that Thornton’s reading extends into the twentieth century, I suspect editor Salmonson may have tied that final bow on the tale herself, as I know her devotion to the British author all too well.

The setting of “The Inhabitant of the Pond” is virtually a gothic cliché: a gloomy and decaying house of indeterminate size whose three surviving inhabitants appear to live in complete isolation. Their home could easily be a scaled-down version of the House of Usher, with the latter’s “black and lurid tarn” reduced to a “dismal spot [that] had once been a picturesque little marble-bottomed pond, with an abundance of lily pads and fish…” The isolated setting is as stark as a modernist stage set, and one wonders if Linda Thornton is not actually channeling Thornton Wilder here a bit. All interior action is restricted to the protagonist’s second floor bedroom and a few spaces mentioned in passing—kitchen, study, staircase. The single outdoor setting, which is the focus of the story, is that same “dismal spot” where the statue of a “cherub had reigned as a benevolent shade.”

By the time of the events that comprise the bulk of the narrative, fifteen years of neglect have seen the transformation of this pond into “a choked, moss-covered sanctuary for fat, torpid insects, while the guardian statue had assumed the aspect of an eroded tombstone.” On the next page the protagonist-narrator reveals that these fifteen years have also witnessed the death of both her mother and her older brother Thomas, along with the departure of any remaining servants, leaving her alone in the house with her father and her younger brother Edward. And so the stage is set.

By the time of the events that comprise the bulk of the narrative, fifteen years of neglect have seen the transformation of this pond into “a choked, moss-covered sanctuary for fat, torpid insects, while the guardian statue had assumed the aspect of an eroded tombstone.” On the next page the protagonist-narrator reveals that these fifteen years have also witnessed the death of both her mother and her older brother Thomas, along with the departure of any remaining servants, leaving her alone in the house with her father and her younger brother Edward. And so the stage is set.

Beyond the descriptions of lush vegetation, vaguely suggestive of the Deep South, the lack of any identifiable geographical location or historical context for the story leaves the reader with an impression of events that are happening both out of place out of time. The feeling is similar, and perhaps echoes, the effect that Poe cultivated so well in stories like “Usher,” in which it is never clear when or even in which hemisphere the tale takes place.

My surmise is this combination of effects that succeeds in “The Inhabitant of the Pond” is also a blend of the deliberate and the accidental, a somewhat wobbly shot that managed nonetheless to nail the very edge of the bullseye, part genuine talent and part beginner’s luck. The overall Poe-filtered gothic vibe probably reflects the author’s own aesthetic, whereas the minimalist theatrical construction of the tale seems more likely an artifact of the presentation of this aesthetic via her limited artistic palette. All these elements combine to create an almost numinous but slightly off-kilter version of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt, positioning the reader in uncomfortable proximity to the characters. Meanwhile the spare and simple brushstrokes and dark pigments with which Thornton limns her scene, marked with spatters of sickly green for plant life and daubs of purple prose in moments of description (brother, beetle, pond), the single stained white streak of the statue to one side, all combine in a portrait that, despite the amateurish moments to which Uncle Stevie points, can yet convey a raw and genuine power. Given that Thornton’s second outing was little more than a ghost of her first (shoot me), and that she seems to have stopped dead in her writing career thereafter, we will never know whether “The Inhabitant of the Pond” was her best shot or the lost harbinger of things that might have been.

My surmise is this combination of effects that succeeds in “The Inhabitant of the Pond” is also a blend of the deliberate and the accidental, a somewhat wobbly shot that managed nonetheless to nail the very edge of the bullseye, part genuine talent and part beginner’s luck. The overall Poe-filtered gothic vibe probably reflects the author’s own aesthetic, whereas the minimalist theatrical construction of the tale seems more likely an artifact of the presentation of this aesthetic via her limited artistic palette. All these elements combine to create an almost numinous but slightly off-kilter version of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt, positioning the reader in uncomfortable proximity to the characters. Meanwhile the spare and simple brushstrokes and dark pigments with which Thornton limns her scene, marked with spatters of sickly green for plant life and daubs of purple prose in moments of description (brother, beetle, pond), the single stained white streak of the statue to one side, all combine in a portrait that, despite the amateurish moments to which Uncle Stevie points, can yet convey a raw and genuine power. Given that Thornton’s second outing was little more than a ghost of her first (shoot me), and that she seems to have stopped dead in her writing career thereafter, we will never know whether “The Inhabitant of the Pond” was her best shot or the lost harbinger of things that might have been.

One last peculiar aspect of this story deserves mention here: the climactic scene when the giant invisible arthropod can be heard offstage smashing its way up the stairs seems much too close to the ending of another story Michael and I have already covered in this series to be coincidental, though it almost certainly is. Compare these lines from Thornton’s tale: “…at that moment there came a dreadful roaring and crashing sound from below…The thumping drew closer. It might have been a person walking, but there was never a human gait that sounded like that. Too heavy, too awkward, too fast. Too many legs…”

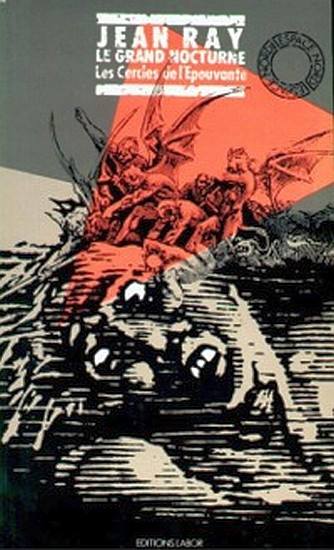

…to this passage from the climax of Jean Ray’s << La scolopendre >> [“The Centipede”], with which we closed the original series of Stories from the Borderland:

…to this passage from the climax of Jean Ray’s << La scolopendre >> [“The Centipede”], with which we closed the original series of Stories from the Borderland:

<<…une autre [porte] s’ouvrit aussitôt poussée formidable…Un bruit innouï, comme celui d’une foule, montait à la present, énorme, invraisemblable. L’escalier gémit. >>

“Instantly another door opened beneath some enormous force…A noise came now like none they’d ever heard before, like the impossible sound of an incredible crowd. The stairs groaned.” [translation mine]

Time and again the research that Michael and I have done for Stories from the Borderland has led us to unexpected connections between works in all literary strata and all media…but this one, which is impossible to ignore for anyone who has read both stories, seems inexplicable. << La scolopendre >> has never been published in English translation. Though Jean Ray, whose work so often inhabits the intersection of the gothic, The Weird, and the conte cruel (and which I have often described as a mix of Jim Thompson and Poe), actually seems an excellent match for Thornton’s aesthetic. Is it possible she could have read it in the original French?

Ray’s tale first appeared in the journal La Parole universitaire in 1932. It was reprinted in the 1942 collection Le Grand Nocturne, and again in 1961, in Les 25 meilleures histoires noires et fantastiques. If Thornton knows French, she most likely read it in the latter. Neither her two published stories nor her Facebook page offer any indication that she is literate in a language other than English. One might legitimately expect the sort of untranslated epigraphs and allusions of which Poe was so fond, and an appropriate quote from some continental author would have worked wonderfully well in either tale. In the end there are some rocks even I won’t overturn, and some mysteries that must remain unexplained. Isn’t this how we honor The Weird?

<< L’incertitude seule nous rend irresponsables. Il faut donc savoir la garder, —sinon, qui donc oserait accomplir quelque chose! >>

—Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, L’Éve future

Here is the link to Michael Bukowski’s interpretation of the “Inhabitant” itself. I am excited to share this with you all at last, as the art has been done for some time, and as you can see, Michael put a lot of love into it. And with that, Michael and I conclude the third series of Stories from the Borderland. Thus far we have offered sixteen episodes, sixteen portraits of stories lurking just outside the unwholesome firelight of whatever passes for a canon of Weird Fiction: portraits of stories, and of the monsters that inhabit them. We both hope you have enjoyed this project as much as we have.

Though we pause here, Stories from the Borderland is not done. Michael and I have already begun to line up the stories for a fourth series, and I know his art fingers are itching for a crack at some of these creatures we are considering. In the meantime, we are collecting all sixteen episodes (#16 is the epic study of A.E. Van Vogt’s “The Black Destroyer” and “Discord in Scarlet” that appeared only in Issue 84 of Stu Horvath’s Unwinnable Monthly (the MONSTER ISSUE). We are also planning a special panel at NecronomiCon Providence this August, at which we will reveal a new episode, with new art, LIVE, after the manner of the legendary “cartoon concerts” pioneered by Vaughn Bode and his son Mark Bode. As part of this panel, Anya Martin will also reveal some of the discoveries she made on the trail of Allison V. Harding. Finally, artist Jeanne D’Angelo and I are planning a second parallel series, tentatively titled Tales from the Crossroads, that will examine stories by canonical authors that dip the barest toe into The Weird, often with results that fully justify architect Mies Van der Rohe’s adage that “Less is more.” Our plan is also for this series to explore the increasing intersection between Weird Fiction and Speculative Realism, Object Oriented Ontology, and the Nonhuman Turn. So if you like to look at monsters, or to stare too long into the Abyss, stick with us. We’re not done with you yet.

Leave a Reply