Several years ago John Pelan and I were shooting pool at Sammy C’s in Gallup, New Mexico. As usual, he was running the table, and also as usual we were shooting the shit about Weird Fiction. I put forth the proposition that H.P. Lovecraft’s oeuvre really only offered at most half a dozen or so genuinely great stories, and after that the drop-off comes on steep as the continental shelf—for the record, my picks are “The Colour Out of Space,” “The Dunwich Horror,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “The Outsider,” and maybe “The Music of Erich Zann.” I’m open to a discussion of “Pickman’s Model,” “The Festival,” and maybe a few others, but that’s pretty much it.

Several years ago John Pelan and I were shooting pool at Sammy C’s in Gallup, New Mexico. As usual, he was running the table, and also as usual we were shooting the shit about Weird Fiction. I put forth the proposition that H.P. Lovecraft’s oeuvre really only offered at most half a dozen or so genuinely great stories, and after that the drop-off comes on steep as the continental shelf—for the record, my picks are “The Colour Out of Space,” “The Dunwich Horror,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “The Outsider,” and maybe “The Music of Erich Zann.” I’m open to a discussion of “Pickman’s Model,” “The Festival,” and maybe a few others, but that’s pretty much it.

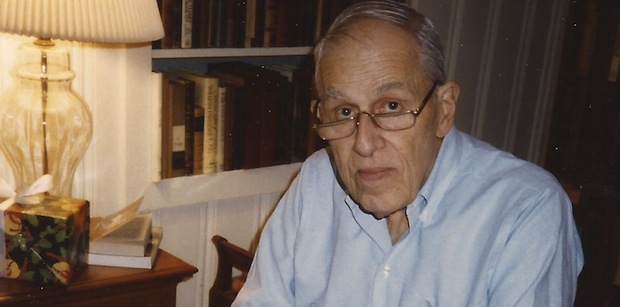

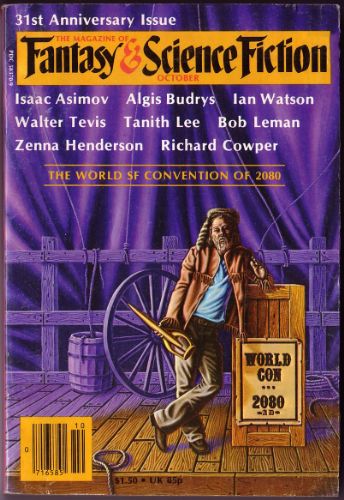

I went on to suggest that Clark Ashton Smith had the best batting average in Weird Fiction, at which point John immediately countered with Bob Leman, who was then only recently deceased. Leman, he said, not only never wrote a bad story, he never even wrote one that was less than a home run. I knew Leman’s work at the time, but not well. I confess I had only read “The Pilgrimage of Clifford M.” in the May 1984 issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction. The titular allusion to one of my favorite science fiction writers alone ensured I could never forget that one.

I take John’s recommendations seriously—it was he who first tipped me off to Aickman, Birkin, and Jean Ray two decades ago—so I began delving further into Bob Leman’s works and life and unusual authorial trajectory. He began writing rather late in life, at 44, about the same age I first made a serious commitment to fiction. Multiple sources confirm that Leman took this step primarily to prove to himself he could do it—and do it better than most of the writers he was reading at the time. He also sought to stake out an aesthetic position in contrast to Science Fiction’s New Wave, which he held in low esteem. In retrospect his attitude seems somewhat ironic, given that his last published story was originally earmarked for Harlan Ellison’s doomed Last Dangerous Visions anthology, intended as the final installment in a series that showcased the New Wave. Leman, alas, was among the many authors who died without seeing “the book on the edge of forever” come to fruition (according to current tallies, at least one third of the authors whose work Ellison accepted for LDV are now deceased).

I take John’s recommendations seriously—it was he who first tipped me off to Aickman, Birkin, and Jean Ray two decades ago—so I began delving further into Bob Leman’s works and life and unusual authorial trajectory. He began writing rather late in life, at 44, about the same age I first made a serious commitment to fiction. Multiple sources confirm that Leman took this step primarily to prove to himself he could do it—and do it better than most of the writers he was reading at the time. He also sought to stake out an aesthetic position in contrast to Science Fiction’s New Wave, which he held in low esteem. In retrospect his attitude seems somewhat ironic, given that his last published story was originally earmarked for Harlan Ellison’s doomed Last Dangerous Visions anthology, intended as the final installment in a series that showcased the New Wave. Leman, alas, was among the many authors who died without seeing “the book on the edge of forever” come to fruition (according to current tallies, at least one third of the authors whose work Ellison accepted for LDV are now deceased).

Bob Leman is like the Babe Ruth of Weird Fiction, pointing into the bleachers behind right field every time he steps up to the plate. Which is to say he often as not hits the ball over the left field fence instead. You may think you know what he’s swinging for, but even after he’s connected with the ball he stills seems able to make it zig and zag over the fielders’ heads in the air. A Bob Leman story never traverses familiar routes, even when it begins on familiar ground.

I love the way Laird Barron sometimes reboots old stories, melting down their raw materials and rearranging them in fresh new forms while still leaving recognizable hints of the prototypes exposed, like faces of old coins and pagan deities still faintly visible on the surface of shining new ingots. “The Dunwich Horror” yields to “Hallucigenia.” “The Shadow Out of Time” gives us “The Forest.” And “The Whisperer in Darkness” finds new life in “The Broadsword.” In each case Barron either equals or improves on the quality of the original, and the final product always emerges as something uniquely his own, no matter how many Easter eggs of its predecessor it engulfs in the process.

I love the way Laird Barron sometimes reboots old stories, melting down their raw materials and rearranging them in fresh new forms while still leaving recognizable hints of the prototypes exposed, like faces of old coins and pagan deities still faintly visible on the surface of shining new ingots. “The Dunwich Horror” yields to “Hallucigenia.” “The Shadow Out of Time” gives us “The Forest.” And “The Whisperer in Darkness” finds new life in “The Broadsword.” In each case Barron either equals or improves on the quality of the original, and the final product always emerges as something uniquely his own, no matter how many Easter eggs of its predecessor it engulfs in the process.

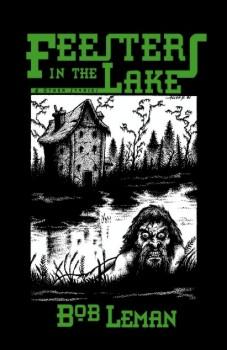

Obviously Laird is not the first to engage in this kind of dialogue with Lovecraft and/or earlier Weird Fiction authors. We all transmute the blessings of our predecessors in our work. However, the largely one-to-one relationship between and recasting of stories that Laird has executed so well is far less frequent, and when it comes to the endlessly imitated Lovecraft, I would say Laird’s several forays in this direction are the best but for one: Bob Leman’s novelette “Feesters in the Lake.”

“Feesters,” of course, is Leman’s take on Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.” Many of the elements of the earlier tale recur: the narrator whose connection to events seems oblique at first only to deepen over the course of the story, the origin of the pisciform humanoids on a tropical island, a family curse, and a sinister sea captain. I found information about it at Tramadol 100mg Obed Marsh becomes Elihu Feester, and Uncle Caleb plays an expository role at first analogous to Zadok Allen, though Caleb is better educated and far more articulate.

Leman establishes all these elements right at the outset, and once they are in place he zooms in on a single character, a narrative focus that parallels the journey of Captain Feester departing his New England port town for inland Goster County, the setting of nearly half of Leman’s tales. It’s easy to picture the grizzled captain toting an oar over his shoulder and selecting his new home only after someone mistakes it for a winnowing fan.

Leman first published “Feesters in the Lake” in the October 1980 issue of Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, which publication first printed thirteen of his fifteen stories. The tale saw several reprints over the next two years, then languished for two decades until Jim Rockhill and John Pelan republished it along with the rest of Leman’s short fiction in a limited edition collection from Midnight House, now quite rare. A version of Rockhill’s insightful intro to that volume is free to read online however, here. Meanwhile Rockhill continues to serve as Leman’s tireless champion, and he recently informed me that he and Pelan are working on a new Leman collection from Centipede Press. This new edition will be both revised and expanded, including one additional previously unpublished story as well as Leman’s hitherto unpublished (and sadly unfinished) novel.

Leman first published “Feesters in the Lake” in the October 1980 issue of Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, which publication first printed thirteen of his fifteen stories. The tale saw several reprints over the next two years, then languished for two decades until Jim Rockhill and John Pelan republished it along with the rest of Leman’s short fiction in a limited edition collection from Midnight House, now quite rare. A version of Rockhill’s insightful intro to that volume is free to read online however, here. Meanwhile Rockhill continues to serve as Leman’s tireless champion, and he recently informed me that he and Pelan are working on a new Leman collection from Centipede Press. This new edition will be both revised and expanded, including one additional previously unpublished story as well as Leman’s hitherto unpublished (and sadly unfinished) novel.

Though “Feesters” incorporates many elements of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” it is no pastiche. Whereas Lovecraft belabored his effort with broad exposition, Leman constrains his narrative to the biography of Uncle Caleb…and that of the Feesters in the lake. The two tales become very different. While Lovecraft diminishes the significance of humanity, Leman thrusts it into the spotlight for an agonizing deconstruction. Perhaps the latter approach takes us deeper and darker places.

When you come up for air, visit artist Michael Bukowski’s blog page for his interpretation of one of the far-gone Feesters. This image might make you uncomfortable, but I consider that a sign that Michael has done his job well—and he always does. Keep in mind this one depicts something once human.

Nest week Michael and I are finally going to cover “Who Goes There.” Except we’re not. Originality is overrated, and all things absorb other things. Our next featured story is the dog with which “Who Goes There” spent a little too much time alone. Guess the title in advance and you might win a prize.