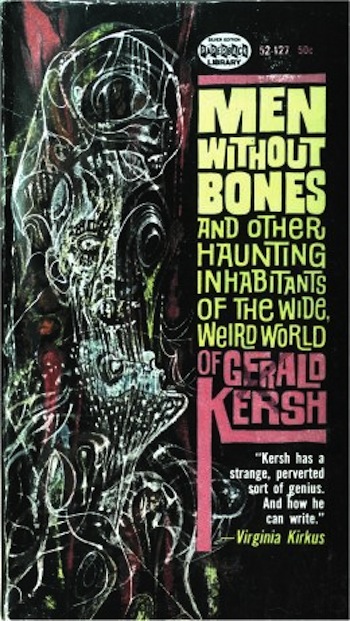

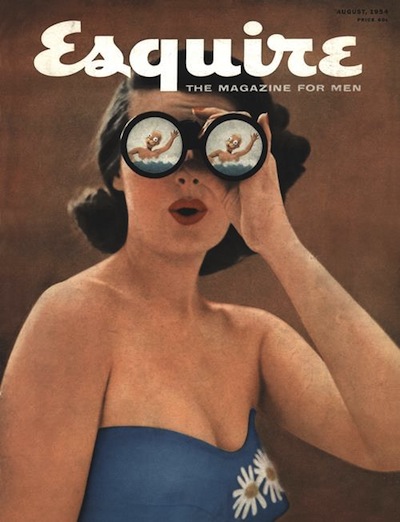

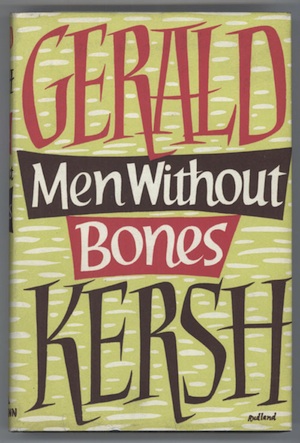

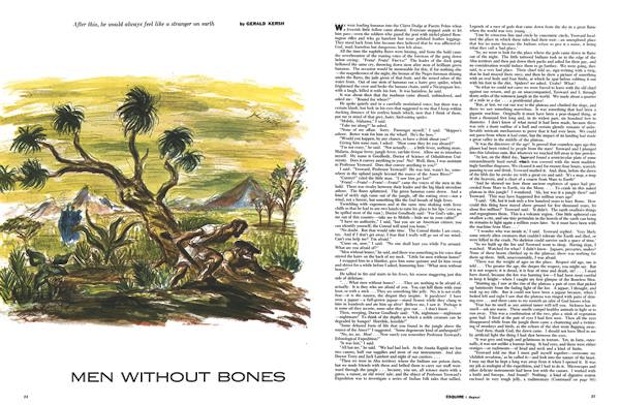

Gerald Kersh’s “Men Without Bones” presents a virtual case study in the awkward position of midcentury Weird Fiction. A truly—literally—pulpy tale, its original publication in 1954 came not in Weird Tales but in Esquire. By that time the pulps themselves were moribund, while new markets were arising. Michael Kelly and I recently discussed on The Outer Dark how mainstream literary journals are currently publishing some of the best Weird Fiction, but here we find ourselves more than 60 years back with a classic of unfiltered cosmic horror in a magazine whose literary reputation was already established by authors including Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Gide. Despite such an auspicious initial placement, regardless of at least two dozen reprints since, or the fact that it remains in print today, I will wager “Men Without Bones” remains unknown to much of The Weird’s contemporary readership.

Gerald Kersh’s “Men Without Bones” presents a virtual case study in the awkward position of midcentury Weird Fiction. A truly—literally—pulpy tale, its original publication in 1954 came not in Weird Tales but in Esquire. By that time the pulps themselves were moribund, while new markets were arising. Michael Kelly and I recently discussed on The Outer Dark how mainstream literary journals are currently publishing some of the best Weird Fiction, but here we find ourselves more than 60 years back with a classic of unfiltered cosmic horror in a magazine whose literary reputation was already established by authors including Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Gide. Despite such an auspicious initial placement, regardless of at least two dozen reprints since, or the fact that it remains in print today, I will wager “Men Without Bones” remains unknown to much of The Weird’s contemporary readership.

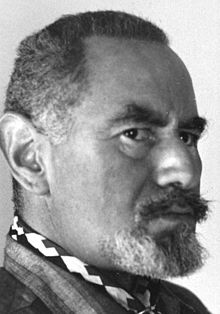

Kersh was a powerful man as well, a former professional wrestler with a reputation for classic strongman showmanship: tearing phone books in half, bending dimes with his teeth, chopping down trees with his beard. Though he was able to draw heavily on personal experience in his crime fiction—identifying his novels as essentially autobiographical—he wrote widely across genres and made more than one trek through The Weird. I first encountered his work over 45 years ago right alongside Lovecraft, John Collier, and E. Everett Evans, in one of Betty Owen’s anthologies for Scholastic. Kersh seems to have been a particular favorite of Owen’s as she sometimes included two of his stories in the same anthology. Though Kersh’s candle has dimmed, it has never gone out, and Valancourt Books has fortunately reprinted much of his work over the last few years.

For all Kersh’s power as a writer however, “Men Without Bones” is a story that really shouldn’t work, a literary bumblebee flight. The scenario is hackneyed, the setting all wrong for the premise, the archaeology cartoonish, the surprise ending disintegrates after only the briefest consideration. And yet it does work, precisely because of Kersh’s strength. The archaeologists from “Osbaldeston University” on their doomed expedition into the jungle may be cardboard cutouts, but they get us quickly where we need to go…where Kersh can deliver.

How often does one begin reading a story with a promising title, only to watch it fall flat, failing to deliver the anticipated frisson of The Weird? Kersh makes good on his title’s promise. There is no bait and switch. “Men Without Bones” is full of men without bones, and these gelatinous horrors are every bit as creepy and crawly as one might hope, their slow motion depredations disturbing and dreadful. If you like to look at monsters, the payoff is real: “…out of that stinking green twilight came a horde of those jellyfish things. They poured up the tree, and writhed along the branch.” There is plenty of pouring and writhing and oozing and…feeding. Vividly yet with great economy, Kersh creates one of the truly great horrors of The Weird, yet his monsters are not the complex composites of Lovecraftiana, with their feelers and claws and waving appendages, doled out in mind-shattering glimpses. The men without bones are horrific in their utter simplicity…and in their history.

Like much of the best Cosmic Horror, Kersh’s story is presented as science fiction. What poor Professor Yeoward and his assistant Dr. Goodbody entered the jungle to find was not the hideous men without bones, but something else entirely, something that fell from the heavens “in a great flame when the world was very young.” They find first more than they dreamed of, then more than they bargained for, as the greatest discovery of the century is haunted by beings from an ancient nightmare, humanity’s oldest enemies…

And then comes the ending, that classic old school O. Henry ending. It’s completely ridiculous, utterly implausible, in direct contradiction to parts of the story. It hits like a punch in the gut, but seems laughable a minute later…until you try to shake it off. Because you can’t. Ever. Just as I have never been able to look at the Mona Lisa’s smile since I read “The Ape and the Mystery” when I was seven years old. As the years go by, I find it harder and harder not to believe that Kersh was right about that one.

Interestingly Kersh’s story precedes the pseudoscientific claims of von Däniken by over a decade, as well as the sources he plagiarized, such as Robert Charroux’s Histoire inconnue des hommes depuis cent mille ans (1963) and Le matin des magiciens by Pauwels and Bergier (1963). If not for its precedence, the ending of “Men Without Bones” would seem to be deliberate mockery of these later writers’ hokum, yet if that is so Gerald Kersh was entirely prescient, a writer of such greatness he could call bullshit before the bullshit even got shat. Or…considering Kersh actually uses the phrase “Legends of a race of gods that came down from the sky” long before any of them…could it be that von Däniken, Charroux, Pauwels and Bergier, all so much given to plagiarism themselves, were actually usurping their premise from Kersh’s squishy little gem? What a grand twist that would be in the end, though perhaps it’s best not to think too hard about where anything really came from in the beginning.

Michael Bukowski really…sank his teeth into this one. You can see his portrayal of one of the little fat men who come at dusk here: https://yog-blogsoth.blogspot.com/2016/03/man-without-bones.html. For those of you who read the story after this, you will notice he worked a very clever Easter egg into his design, picking up on an unusual biological reference that Kersh employed.

Michael Bukowski really…sank his teeth into this one. You can see his portrayal of one of the little fat men who come at dusk here: https://yog-blogsoth.blogspot.com/2016/03/man-without-bones.html. For those of you who read the story after this, you will notice he worked a very clever Easter egg into his design, picking up on an unusual biological reference that Kersh employed.

Join us next week when Michael and I take you for a nighttime tour of a story by one of the most famous names in science fiction. It’s a simple story, one character, no dialogue, lots of dread. As always, guess the story in advance and you might win a prize.

Leave a Reply