When Michael Bukowski and I first conceived this series, our working title was something like “Great Weird Stories Hidden in Plain Sight.” I must take responsibility for that stillborn monstrosity, alas. Fortunately Michael suggested the much more felicitous rubric under which we debuted and now operate. I mention this here because this week’s tale exemplifies that original concept perhaps better than any other.

When Michael Bukowski and I first conceived this series, our working title was something like “Great Weird Stories Hidden in Plain Sight.” I must take responsibility for that stillborn monstrosity, alas. Fortunately Michael suggested the much more felicitous rubric under which we debuted and now operate. I mention this here because this week’s tale exemplifies that original concept perhaps better than any other.

The Weird has been with us a long time. I have argued elsewhere that as a phenomenon it even predates us, and those of us who practice its literary aspect can trace our lineages at least as far back as the late nineteenth century. Yet is only in the current century that terms such as “Weird Fiction” and “Weird Horror” have gained any real currency as a medium of exchange between writers, readers, editors, publishers, and artists. For most of its literary history, The Weird has dwelt symbiotically within the houses of other branches of the fantastic, most notably in science fiction, and if we truly seek to grasp the true extent of its evolution, we must learn to identify its exemplars and tweeze them out of their cubbyholes even when they appear to be something else.

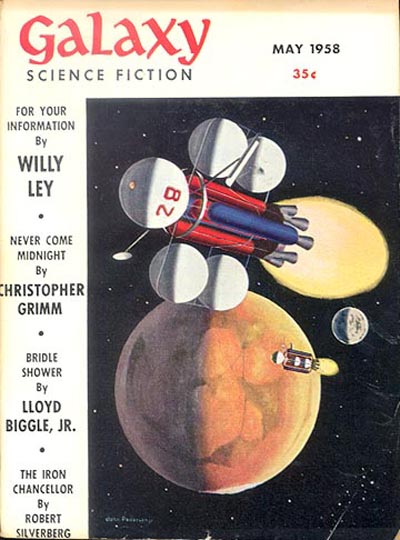

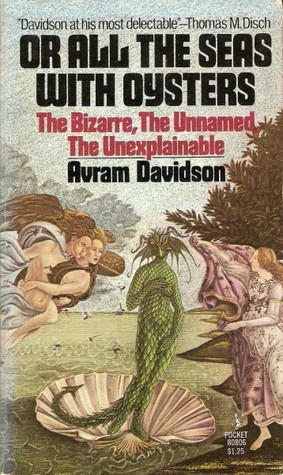

Though primarily remembered as a science fiction author—and primarily known as one during his career—Avram Davidson not only wrote in multiple genres, he mixed, split, and wrote across them. He won major awards in science fiction, fantasy, and mystery (including four World Fantasy Awards—the fourth for Lifetime Achievement—which tells me I have some catching up to do). All this makes his oeuvre a fertile fishing ground for hidden Weird Fiction. Nor does one need to cast the line deep: “Or All the Seas With Oysters” was his Hugo winner, and it remains his best known story today. Davidson’s name didn’t even make the cover when the story first appeared in the May 1958 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine, but it has been printed and anthologized dozens of times. In fact, it never really seems to have gone out of print. It is also a perfect little masterpiece of The Weird.

The story begins with the same sort of “Have you ever noticed?” premise that fuels the school of observational comedy most often associated with Jerry Seinfeld. It is worth noting that observational comedy has its own roots in the 1950s, most notably in the work of Shelley Berman, who landed his first major gig as a comedian only the year before “Or All the Seas With Oysters” appeared in Galaxy. Think zeitgeist. Here, the question is: Why are there always so many coat hangers…but never any safety pins?

Ferd, co-owner of the F & O Bike Shop, develops a theory to explain this conundrum: perhaps safety pins and coat hangers are merely separate stages in the life cycle of a single organism, their alternate proliferation and depletion part of a hidden ecology analogous to that of marine invertebrates such as oysters that spawn in the thousands just to produce a few adults. Ferd suggests that these organisms are able to live among us unobserved through their mimicry of familiar objects, and he nicknames them “faux amis,” the standard term in French language instruction for pairs of words that look the same or similar in French and English but have different meanings, such as ancien/ancient, passer/to pass, or blesser/to bless.

The original observation about disappearing safety pins comes in regard to a baby’s diaper, which is appropriate, given that the entire story is about biological life cycles, a pun that was certainly deliberate on Davidson’s part but which he never references directly because he was a damn good writer. The baby enters the story immediately following a discussion of Oscar’s proclivity for disappearing into the nearby park for hours at a time with the bike shop’s female customers. Oscar, of course, is the “O” in F & O. While his partner Ferd worries himself sick over the threat of communists and the conjectural life cycles of creatures from a parallel biology, Oscar maintains a more pragmatic and immediate interest in human reproductive behavior.

The original observation about disappearing safety pins comes in regard to a baby’s diaper, which is appropriate, given that the entire story is about biological life cycles, a pun that was certainly deliberate on Davidson’s part but which he never references directly because he was a damn good writer. The baby enters the story immediately following a discussion of Oscar’s proclivity for disappearing into the nearby park for hours at a time with the bike shop’s female customers. Oscar, of course, is the “O” in F & O. While his partner Ferd worries himself sick over the threat of communists and the conjectural life cycles of creatures from a parallel biology, Oscar maintains a more pragmatic and immediate interest in human reproductive behavior.

All the interests and relationships in the story quickly converge around Ferd’s pet project, a beautiful French racing bicycle of unknown origin. After Oscar temporarily absconds with this prize in order to pursue a particularly athletic young woman on her own American racing bike—only to return it in the damaged condition—Ferd destroys the French machine in a fit of rage. The partnership stands for several weeks in sullen danger of dissolution until Oscar discovers the bike behind the shop, fully restored and pristine. Oscar extends his hand to Ferd in a gestured of renewed friendship, but Ferd claims that the restoration was not his work, that the bike must have regenerated on its own.

Avoiding any further spoilage for those who have not yet read “Or All the Seas With Oysters” (you have your homework assignment now, and there will be a test), let it suffice to say that fortunes of F and O diverge significantly after that. And though Davidson wraps the plot up quite neatly, delivering a perfect gem of a story with the wry and implicit message that symbiosis may be the best answer, he ends nonetheless in the grand tradition of The Weird, leaving the reader with unanswered questions about the creatures he described, most notably: What eats the safety pins?

Michael Bukowski completes this installment of Stories From the Borderland with his illustration of the life cycle of the French Racer at his blog:, so be sure to take a look. We are not quite done though, as this episode comes with an odd little coda. When Michael first described his planned illustration to me, he mentioned coat hangers and safety pins. I, of course, promptly corrected him, reminding him that the story is about coat hangers and paper clips. Only it’s not. I’ve read this story at least four times, the first in the early ‘70s, but most recently within the last few months, and I have always remembered paper clips. I didn’t give my error any more thought until a few weeks later when I was describing this project to author/editor/publisher John Pelan at his home. And John, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of genre fiction, replied, “But it is paper clips.” Only it’s not.

I have since made this inquiry of others I know who have already read the story, and all those who read it in the 1970s remember paper clips, while all those who read it later remember safety pins. It appears that “Or All the Seas With Oysters” might be another bit of evidence for the “Berensteain Bears Effect,” the theory that somewhere around 1978 either a glitch in the matrix or a careless time traveler caused the Berenstein Bears to become the Berenstain Bears. Predictably, I am also among those who remember it as the former. I’ve kept my vacuum cleaner locked up since then…

Next week Michael will be featuring creatures from the works of E.F. Benson, so be sure to visit his blog for that. Stories From the Borderland will return on Dec. 30 with another neglected masterpiece of Weird Horror. Over the last couple years Jeff VanderMeer has shown us how The Weird can be a powerful vehicle for an ecological message. Next week’s story also comes from an author who, like Avram Davidson, was best known for both science fiction and short stories (and who is represented in the VanderMeers’ landmark anthology The Weird, though not by the story we have chosen). In this case, the author had the special intelligence to use the concept of mimicry to present a deep and horrific ecological parable thirty years ago, a story that will lead you out to sea and leave you gasping. Guess it if you can. Perhaps you will win a prize.