“Stevie and The Dark”

“Stevie and The Dark”

“Hush!”

“And a Little Child—”

“The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.”

Isaiah 11:6, KJV

Many are the reasons why great Weird stories slip through the cracks of whatever passes for a canon of Weird Fiction. Slip through the cracks, fly under the radar, remain hidden by a veil, obscured by clouds…choose your metaphor. Canon may not be the right word either for this thing we share, but it’s our thing, and we all need to work on it together. Here at Stories from the Borderland, we take that mission seriously. so damn the would-be gatekeepers, full steam ahead! Over the last couple years, Michael Bukowski and I have presented tales that have been forgotten and others that never became memories, formerly ubiquitous stories that haven’t seen a reprint for a generation or more, works by authors whose entire known oeuvres consist of only one or two stories, stories never translated into English, and most of all, stories hidden in plain sight that no one thinks of as Weird because everyone identifies their authors with science fiction, fantasy, or mainstream lit. Here are purloined letters of Weird Fiction, if you will, though here we are liberating what never had to be stolen in the first place.

Even in this company, Zenna Henderson is a special case. Not only was she one of a very few mid-century female authors publishing science fiction under her own name (along with Margaret St. Clair, whom we have previously featured), her approach to the genre was vastly different from most of the Campbellian “Golden Age” science fiction writers, with the exception of the “pastoralist” Clifford D. Simak, to whom she is often compared, and whose work shares a combination of rural settings and a certain tonal background with Henderson’s. I realize, though, that Simak is both fraught and apt as a reference point, in that neither author is a household name today, even in houses where spec lit maintains a hold. The fact that the most frequently invoked comparison point for Henderson’s fiction is an increasingly obscure male author should emphasize the overall uniqueness of both her work and her position in speculative fiction.1 There really was no one like her, nor has there been since (except maybe Nnedi Okorafor).

Even in this company, Zenna Henderson is a special case. Not only was she one of a very few mid-century female authors publishing science fiction under her own name (along with Margaret St. Clair, whom we have previously featured), her approach to the genre was vastly different from most of the Campbellian “Golden Age” science fiction writers, with the exception of the “pastoralist” Clifford D. Simak, to whom she is often compared, and whose work shares a combination of rural settings and a certain tonal background with Henderson’s. I realize, though, that Simak is both fraught and apt as a reference point, in that neither author is a household name today, even in houses where spec lit maintains a hold. The fact that the most frequently invoked comparison point for Henderson’s fiction is an increasingly obscure male author should emphasize the overall uniqueness of both her work and her position in speculative fiction.1 There really was no one like her, nor has there been since (except maybe Nnedi Okorafor).

Which is not to say that Henderson is entirely forgotten as an author. There are many readers who remember her work—whole communities even—often with great affection, even passion. But they remember her work as science fiction. And as a science fiction author they remember her for the “People” stories.

Which is not to say that Henderson is entirely forgotten as an author. There are many readers who remember her work—whole communities even—often with great affection, even passion. But they remember her work as science fiction. And as a science fiction author they remember her for the “People” stories.

Oscar Wilde once said, “There are two ways of disliking my plays: one is to dislike them…the other is to like Earnest,” (Ellmann, 1988: 561-562).2 We may fairly paraphrase that here as “There are two ways of ignoring Zenna Henderson’s writing: one is to ignore her writing. The other is to like the People stories.”

Am I throwing shade on the People stories? No. They remain Henderson’s greatest legacy. And they are important. Over the years they have become ever more important to people from many disenfranchised demographics. If you have ever seen yourself as an outsider, it’s easy to see yourself in the People stories, and to embrace that message of hope, that message that somewhere, out in the real or metaphorical desert, there are others like yourself. And you will find them. The message that it gets better, at least it does if you can find your community, the lost place of belonging that you still feel inside. For those who can find it.

Of course the People stories are “Mormon-coded,” though in a different way than the fiction of other LDS genre writers such as Orson Scott Card. I will even make the explicit value judgement and say: a better way. Which is why Henderson’s work can speak to some of the very communities that the LDS Church disenfranchises so violently. Not surprisingly, her relationship to the Church was problematic: records show she no longer attended LDS services or participated in the Church after she married a nonmember in 1943 . Thus by the time she began publishing fiction in the early 1950s, she had not been an active member for almost a decade, though whether she ended that relationship or the Church did, remains unclear. Clearly however, certain elements of LDS doctrine remained important to her throughout her life, particularly the narrative of the Church’s exodus and foundation in the high desert of Utah. I would argue that her ability to abstract these elements from the Church itself represents the very engine of the People stories and the basis of their enduring value for so many other(ed) groups.

Of course the People stories are “Mormon-coded,” though in a different way than the fiction of other LDS genre writers such as Orson Scott Card. I will even make the explicit value judgement and say: a better way. Which is why Henderson’s work can speak to some of the very communities that the LDS Church disenfranchises so violently. Not surprisingly, her relationship to the Church was problematic: records show she no longer attended LDS services or participated in the Church after she married a nonmember in 1943 . Thus by the time she began publishing fiction in the early 1950s, she had not been an active member for almost a decade, though whether she ended that relationship or the Church did, remains unclear. Clearly however, certain elements of LDS doctrine remained important to her throughout her life, particularly the narrative of the Church’s exodus and foundation in the high desert of Utah. I would argue that her ability to abstract these elements from the Church itself represents the very engine of the People stories and the basis of their enduring value for so many other(ed) groups.

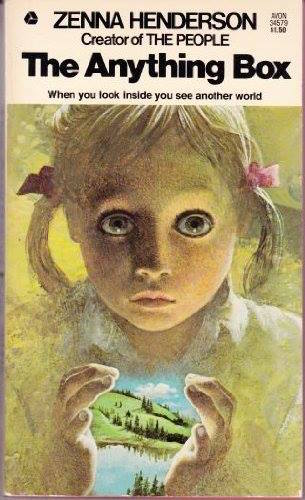

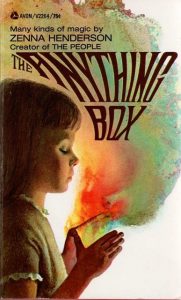

In a 2009 article about Henderson at Tor.com, author Jo Walton wrote “All her stories are very sweet, and they’re almost all about teachers and children and being special.” Clearly Walton was describing only the People stories, or she would have qualified the first clause of that sentence with its own “Almost…” Henderson wrote a handful of stories with a rough saw-toothed edge, and those are the stories she collected in The Anything Box.

In a 2009 article about Henderson at Tor.com, author Jo Walton wrote “All her stories are very sweet, and they’re almost all about teachers and children and being special.” Clearly Walton was describing only the People stories, or she would have qualified the first clause of that sentence with its own “Almost…” Henderson wrote a handful of stories with a rough saw-toothed edge, and those are the stories she collected in The Anything Box.

Although The Anything Box was Henderson’s second published book, following The Pilgrimage, a sort of mosaic novel cobbled together from the earliest People stories, it contains her first published story, “Come on Wagon,”4 along with more than half the fiction she published during her first decade as a publishing author. Her fiction continued to alternate between People and non-People stories throughout her career, but by the early Sixties, even the stories from outside the People cycle took on a similar gentle tone.

Although The Anything Box was Henderson’s second published book, following The Pilgrimage, a sort of mosaic novel cobbled together from the earliest People stories, it contains her first published story, “Come on Wagon,”4 along with more than half the fiction she published during her first decade as a publishing author. Her fiction continued to alternate between People and non-People stories throughout her career, but by the early Sixties, even the stories from outside the People cycle took on a similar gentle tone.

Have you noticed that Weird stories about children seem most effective when told from the perspective of a child? Michael and I have. Consider “The Shed” by E. Everett Evans (Stories from The Borderland #2), “The Specialist’s Hat” by Kelly Link, “Rotifers” by Robert Abernathy, or “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” by Conrad Aiken. Even when Henderson wasn’t writing about the People, she almost always wrote about children, and a large proportion of her short fiction is told from the perspective of a child or a schoolteacher. Teaching was Henderson’s day job, so she was writing what she knew. Some of what she wrote from a teacher’s perspective is surprisingly edgy too, but children were really her specialty.

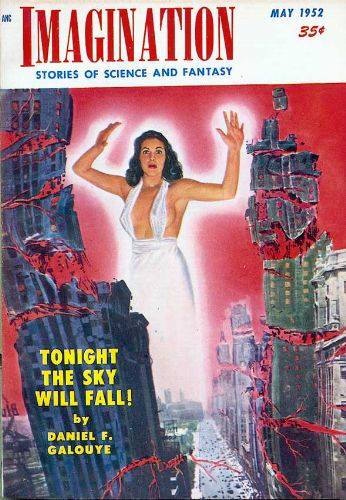

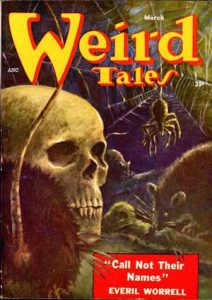

“Stevie and The Dark” first appeared as “The Dark Came Out to Play” in the May 1952 issue of Imagination. It was Henderson’s third story to see print. As Michael Bukowski was quick to note when we were choosing from Henderson’s work for this installment of Stories from the Borderland, this is quite a bit like another tale we have already examined, “Brenda” by the aforementioned Margaret St. Clair, which came out in the March 1954 issue of Weird Tales. In both stories, a young person encounters a dangerous and amorphous monster in a rural area…and both arguably thus may draw upon an even earlier story, Theodore Sturgeon’s “It” from the August 1940 issue of Unknown. As we have noted here before, without a smoking gun one can never know which resemblances represent actual influence and which are simply the result of ideas adrift in the zeitgeist, as with the near-simultaneous discovery of non-Euclidean geometry by Nikolai Lobachevsky and János Bolyai c. 1830, springing up like violets as Bolyai and later Charles Olson phrased it.

“Stevie and The Dark” first appeared as “The Dark Came Out to Play” in the May 1952 issue of Imagination. It was Henderson’s third story to see print. As Michael Bukowski was quick to note when we were choosing from Henderson’s work for this installment of Stories from the Borderland, this is quite a bit like another tale we have already examined, “Brenda” by the aforementioned Margaret St. Clair, which came out in the March 1954 issue of Weird Tales. In both stories, a young person encounters a dangerous and amorphous monster in a rural area…and both arguably thus may draw upon an even earlier story, Theodore Sturgeon’s “It” from the August 1940 issue of Unknown. As we have noted here before, without a smoking gun one can never know which resemblances represent actual influence and which are simply the result of ideas adrift in the zeitgeist, as with the near-simultaneous discovery of non-Euclidean geometry by Nikolai Lobachevsky and János Bolyai c. 1830, springing up like violets as Bolyai and later Charles Olson phrased it.

“Stevie and The Dark” is very much a Weird Tale, and like Kafka’s Odradek or the muck man in “Brenda,” its monster is one of those Cotton-Eyed Joes whose origins and telos are equally unknown:

“Stevie and The Dark” is very much a Weird Tale, and like Kafka’s Odradek or the muck man in “Brenda,” its monster is one of those Cotton-Eyed Joes whose origins and telos are equally unknown:

“How old are you?”

The Dark moved back and forth. “I’m as old as the world.”

Stevie laughed. “Then you must know Aunt Phronie. Daddy says she’s as old as the hills.”

“The hills are young,” said The Dark. “Come on Stevie, let me out. Please—pretty please.”

It is also however one of those relatively rare Weird Tales which is able to incorporate Christian elements as operable tropes, in that Stevie is able to defend himself against “The Dark” by use of a talisman he calls his “pocket piece” but which at the climax of the story is revealed as a popsicle stick crucifix bearing “the magic letters INRI.” Stevie also employs magical colored stones to similar, if less potent, effect, however, so ultimately it remains unclear whether the magic lies with the talismans or with Stevie himself. Considering that “Come on Wagon,” as well as most everything Henderson wrote afterward, was about children with psychic powers, option B seems likely.

One year and several stories later, the child as locus of special powers is once again the focus of her 1953 story “Hush!” Also explicit in this story is the same presentation of children as morally ambiguous that forms a subtle pivot in much of Henderson’s early work. The children in her stories often have great power but lack the experience and frame of reference necessary to understand or even control that power. Stevie in “Stevie and The Dark” almost releases The Dark for the promise of “better magic.” Dubby, the little boy in “Hush!” creates a “Noise-eater” in order to be helpful to his babysitter, but he cannot control his creation: “I’m scared. How do you un-play-like? I didn’t know it’d work so good!”

One year and several stories later, the child as locus of special powers is once again the focus of her 1953 story “Hush!” Also explicit in this story is the same presentation of children as morally ambiguous that forms a subtle pivot in much of Henderson’s early work. The children in her stories often have great power but lack the experience and frame of reference necessary to understand or even control that power. Stevie in “Stevie and The Dark” almost releases The Dark for the promise of “better magic.” Dubby, the little boy in “Hush!” creates a “Noise-eater” in order to be helpful to his babysitter, but he cannot control his creation: “I’m scared. How do you un-play-like? I didn’t know it’d work so good!”

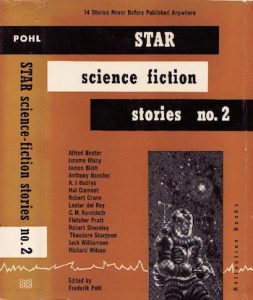

“Hush!” is one of Henderson’s weirdest stories, and one of her darkest. Thematically, tonally, and with its suburban setting and monstrously distorted appliance as antagonist, it would fit easily into an anthology of Philip K. Dick’s work from the same time period, right alongside such stories as “Beyond Lies the Wub” (1952), “Roog” (1953), and “The Father-Thing” (1954). An even more appropriate comparison is with Jerome Bixby’s classic tale of a little boy with godlike powers, “It’s a Good Life,” which also came out in 1953, and later became the basis for the famous 1961 episode of the The Twilight Zone. Bixby’s Anthony is far more powerful and far more dangerous than Henderson’s Dubby, and the story’s outcome and message about the ethical development of children is that much more cynical and disturbing.

“Hush!” is one of Henderson’s weirdest stories, and one of her darkest. Thematically, tonally, and with its suburban setting and monstrously distorted appliance as antagonist, it would fit easily into an anthology of Philip K. Dick’s work from the same time period, right alongside such stories as “Beyond Lies the Wub” (1952), “Roog” (1953), and “The Father-Thing” (1954). An even more appropriate comparison is with Jerome Bixby’s classic tale of a little boy with godlike powers, “It’s a Good Life,” which also came out in 1953, and later became the basis for the famous 1961 episode of the The Twilight Zone. Bixby’s Anthony is far more powerful and far more dangerous than Henderson’s Dubby, and the story’s outcome and message about the ethical development of children is that much more cynical and disturbing.

We should note that William Golding’s Lord of the Flies appeared the following year, in 1954. The comparison is obvious. Clearly there is something prominent in the zeitgeist around this time, a concern about great power in unqualified hands, an issue that Weird Fiction is particularly well-suited to explore. It is that very concern that General Omar N. Bradley voiced only a few years earlier in the oft-quoted line from his Address on Armistice Day: “Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war that we know about peace, more about killing that we know about living.”

We should note that William Golding’s Lord of the Flies appeared the following year, in 1954. The comparison is obvious. Clearly there is something prominent in the zeitgeist around this time, a concern about great power in unqualified hands, an issue that Weird Fiction is particularly well-suited to explore. It is that very concern that General Omar N. Bradley voiced only a few years earlier in the oft-quoted line from his Address on Armistice Day: “Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war that we know about peace, more about killing that we know about living.”

Clearly Zenna Henderson was not the only mid-century author to examine themes of dangerous technology, world destruction, and the darkness beneath the façade of everyday life. And as well as she could handle these topics, others probably addressed them more effectively, or at least more memorably. As the People stories demonstrated however, Zenna Henderson had much more to offer. Although she is likely to always be remembered first for that body of work, and second for a few of her darker stories like “Hush!” and “Stevie and The Dark,” I would argue that her greatest achievement has gone all but unnoticed. Hidden in between the dark and the light of Henderson’s oeuvre are a bare handful of stories that answer one of the most difficult and enduring questions of The Weird: Can Weird Fiction have a happy ending?

One example is the title story of The Anything Box, a tale philosopher-critic sj bagley has described as “a monument to the idea that everything is an object and, as such, objects are everything.” Bagley argues that this tale deserves a central role in the literature of Object Oriented Ontology, and I agree with them (personal communication, 2017). I hope to return to “The Anything Box” in a future installment of Tales from the Crossroads, perhaps capping Henderson’s centenary year next November. For a unique and remarkable take on The Weird however, let us close this essay with a look at the story “And a Little Child—”

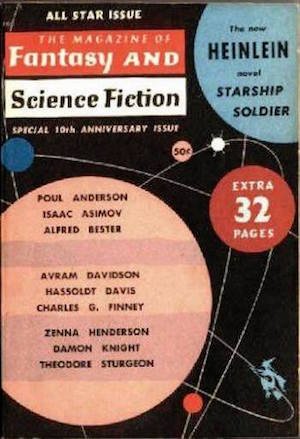

“And a Little Child—” first appeared in the “ALL STAR” 10th Anniversary Issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1959, together with fiction by Isaac Asimov, Alfred Bester, Avram Davidson, and Damon Knight, as well as the first appearance of the first half of Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (as Starship Soldier, Part 1 of 2). Henderson’s presence in this lineup should give some sense of how much her star had risen over the decade, even though her first standalone book was still two years in the future.

“And a Little Child—” first appeared in the “ALL STAR” 10th Anniversary Issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1959, together with fiction by Isaac Asimov, Alfred Bester, Avram Davidson, and Damon Knight, as well as the first appearance of the first half of Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (as Starship Soldier, Part 1 of 2). Henderson’s presence in this lineup should give some sense of how much her star had risen over the decade, even though her first standalone book was still two years in the future.

The child of the story is Liesle, a little girl who has what the older female narrator describes as the “Seeing eyes”: “But there is sometimes among children another seeingness—a seeing that goes beyond the range of adult eyes, that sometimes seems to trespass even on other dimensions. Those who can see like that have the unexpected eyes—the eerie eyes—the Seeing eyes.” The story thus starts ominously enough, and quickly takes a dark twist, as Liesle’s special sight appears to make her equally visible to—or at least susceptible to–the forces of other dimensions, as becomes apparent when the girl is drawn violently into some kind of invisible portal. Henderson portrays this portal very similarly to the “Riemannian cut” in Richard Matheson’s 1953 tale “Little Girl Lost,” which of course became the basis for another celebrated Twilight Zone episode in 1962. As likely as it is that Henderson had read Matheson’s story and drew on it a bit for her own tale, the Twilight Zone version might owe a little to Henderson in turn. Although the teleplay is otherwise a rather straightforward adaptation of its source material, the twist at the end that the portal almost closes before the father can pull his daughter out does not appear in the original story. It is an element of that scene in “And a Little Child—” however.

That scene is not the climax of Henderson’s story as it is in Matheson’s though, only part of the set-up. It is not Liesle who is in danger for most of the rest of the story, but a group of “beasts” that only she can see, or at least that only she can see in their true form, as they appear to everyone else simply as a row of small hills. For all that they resemble Wilbur Whateley’s older brother, the beasts are not threatening and Liesle does not fear them—rather she fears for them, as the beasts themselves are threatened by the onset of cold weather. It is Liesle who must guide the last of them back through the portal. And only Liesle who can.

That scene is not the climax of Henderson’s story as it is in Matheson’s though, only part of the set-up. It is not Liesle who is in danger for most of the rest of the story, but a group of “beasts” that only she can see, or at least that only she can see in their true form, as they appear to everyone else simply as a row of small hills. For all that they resemble Wilbur Whateley’s older brother, the beasts are not threatening and Liesle does not fear them—rather she fears for them, as the beasts themselves are threatened by the onset of cold weather. It is Liesle who must guide the last of them back through the portal. And only Liesle who can.

“And a Little Child—” is very much a Weird Tale—but its ending is very much a happy one. In this, it is a remarkable achievement. Yet it is also a very subtle tale, and a simple one, the sort of tale that is best told with a child at its center. What Henderson accomplished here has largely gone unnoticed, and its significance is hard to convey to anyone who has not read it, like the gift that Liesle withdraws from the portal on her second and final encounter, a glittering something that melts away in her hand, leaving only the memory of fleeting contact with something ineffable and barely glimpsed.

Find Michael Bukowski’s illustrations for all three stories at the following three links: “Stevie and The Dark”, “Hush!”, “And a Little Child—”

Find Michael Bukowski’s illustrations for all three stories at the following three links: “Stevie and The Dark”, “Hush!”, “And a Little Child—”

Two episodes yet remain in this Fourth Series of Stories from the Borderland. Our penultimate selection in this round is a story by an author who was neither Alfred Hitchcock nor H.G. Wells, but which terrified an entire nation when an adaptation was broadcast on TV. If you can believe that and you can correctly guess the name of the original story and its author, we shall offer you a prize.

Footnotes

1As much as I would like to feature a Simak story here—and his fiction contains many Weird elements, including overt nods to Lovecraft in several of his novels—-the best example of a Weird Tale in his oeuvre remains the story he co-authored with Carl Jacobi, “The Street that Wasn’t There.” Alas, that story contains no monsters or creatures for Michael to draw. It is, rather, a story in which the weirdness comes from what is not there that should be, not what is present that should not be. Perhaps we might someday give it a go in Tales from the Crossroads…

2With appropriate irony, Wilde himself was paraphrasing a line from Earnest: “There are two ways of disliking art, Ernest. One is to dislike it. The other, to like it rationally. For art, as Plato saw, and not without regret, creates in listener and spectator a form of divine madness. It does not spring from inspiration but it makes others inspired.”

2With appropriate irony, Wilde himself was paraphrasing a line from Earnest: “There are two ways of disliking art, Ernest. One is to dislike it. The other, to like it rationally. For art, as Plato saw, and not without regret, creates in listener and spectator a form of divine madness. It does not spring from inspiration but it makes others inspired.”

3If you have never read any of the People stories, perhaps you have seen the 1975 Disney film Escape to Witch Mountain, or any of its sequels or remakes? Or perhaps you have at least some idea of the plot of these films? They are an obvious and recognized, if unacknowledged adaptation of Henderson’s work, i.e. they ripped her the fuck off.3A

3AThe really crazy thing is that the film Escape to Witch Mountain was adapted from a children’s novel by Alexander Key published in 1968, almost two decades after Henderson published the first of the People stories. She really needed a better attorney.

3AThe really crazy thing is that the film Escape to Witch Mountain was adapted from a children’s novel by Alexander Key published in 1968, almost two decades after Henderson published the first of the People stories. She really needed a better attorney.

4”Come on Wagon” appeared in the December 1951 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, although it didn’t make the cover. In addition to Henderson’s debut, the issue is notable for the appearance of “O Ugly Bird,” the first of Manly Wade Wellman’s John the Balladeer tales. There were giants in those times…

4”Come on Wagon” appeared in the December 1951 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, although it didn’t make the cover. In addition to Henderson’s debut, the issue is notable for the appearance of “O Ugly Bird,” the first of Manly Wade Wellman’s John the Balladeer tales. There were giants in those times…

Editing/Design: Anya Martin

Leave a Reply