Introduction: Notes from the Artist

By Jeanne D’Angelo

When I first started this illustration, I had no idea that the accompanying essay was going to be about Object Oriented Ontology, or even what that was. However, the opening passage struck me immediately because in it human forms are reduced to some unknowable mystifying shape in the distance. Having more of an understanding of the project now this actually seems like a perfect window into a philosophy that decenters humans and describes objects as having agency outside of our perception of them.

The way I chose to compose this image is meant to echo just that. The foreground/true subject of the painting is a beach littered with both objects specifically described in the story, and objects I could imagine I would feel compelled to pick up if I found them. A crowd scene as it were, with objects clustered, balanced, and woven through each other. To me, all the special objects should be conceivable and unremarkable in most ways, probably manmade refuse but which had taken on an unintended and improbable form. I think the way the story described the small patterned piece of pottery somehow broken into an almost perfect star shape was a perfect example of this type of object. We can deduce it was originally made by human hands, but what kinds of circumstances after its creation could have led to it being in this particular state? This could be the hidden world of objects, with their own trajectories, histories and evolution, and as the story shows, their own ability to act upon human consciousness.

On a purely aesthetic level, this sort of illustration presents an interesting challenge. Often the objects we choose to depict in art are remarkable, ornate, or part of some world of symbolism. The subjects of this image and story are mysterious detritus. Something you might just kick along the sidewalk on your way to run errands. It’s interesting to consider the magical little world of street trash with as much attentive detail as you would a painting of a vase of beautiful flowers or a chest of glittering treasure.

Tales from the Crossroads #1

Tales from the Crossroads #1

By Scott Nicolay

“Aboli bibelot d’inanité sonore.”

—Stéphane Mallarmé, “Sonnet en X”

I allot a significant portion of my time to thinking about The Weird; to considerations of the strange and the uncanny. To cosmic horror. Those who have read any of the essays I have written in collaboration with artist Michael Bukowski under the rubric Stories from the Borderland may have already noticed this predilection. This preoccupation. This fixation. This obsession. I make no pretense that it is healthy.

My interest goes beyond Weird Fiction. As I have written elsewhere, I believe The Weird as a condition—as a thing—exists a priori to human consciousness, to humanity itself, even to existence. Not only is The Weird unknowable—its very ontology is unknowable. It exists outside. Which is why I capitalize it. I ponder at length over its possible manifestations within the realm of our awareness. I hunt the blossoms of the True Weird, the places where it has burst forth into our world, shone darkly through. I pick over the inexplicable, seeking its secret exemplars like Leo Lionni tramping through some Tuscan forest in search of parallel plants. I return over and over again to the Dyatlov Incident, the Taman Shud Case, the Bloop, the 1909 mass sighting of the Jersey Devil in Haddon Heights, New Jersey. Above all I am fascinated with thin places, wrongnesses, parallel universes and cobbly worlds, strange attractors…and objects with agency.

Not even most of my fellow Weird Fiction writers are willing to follow me into that last uncanny valley. Of course traditional mythology and written literature abound with active objects: the One Ring, Gassire’s Lute, Excalibur, Soma’s pylon in Yeelen. They compose a central trope of the Harry Potter books, which together with their film adaptations represent a cultural franchise that is almost globally ubiquitous. But where are such objects to be found in our quotidian world? Most Westerners are uncomfortable with any thought of the inanimate crossing the blood-brick-brain barrier between the imaginative and the real. Anthropologist Sasha Newell has recently bent this boundary inward with his studies of the agency of both Ghanian fetish-objects and the accumulated deposits in the attics, crawlspaces, and storage units of middle America, assemblages that acquire nigh unbreakable holds on their owners. Ultimately however, even these objects possess only such agency as human actors have invested in them. Can objects possess independent agency? This is the koan I have set myself.

Not even most of my fellow Weird Fiction writers are willing to follow me into that last uncanny valley. Of course traditional mythology and written literature abound with active objects: the One Ring, Gassire’s Lute, Excalibur, Soma’s pylon in Yeelen. They compose a central trope of the Harry Potter books, which together with their film adaptations represent a cultural franchise that is almost globally ubiquitous. But where are such objects to be found in our quotidian world? Most Westerners are uncomfortable with any thought of the inanimate crossing the blood-brick-brain barrier between the imaginative and the real. Anthropologist Sasha Newell has recently bent this boundary inward with his studies of the agency of both Ghanian fetish-objects and the accumulated deposits in the attics, crawlspaces, and storage units of middle America, assemblages that acquire nigh unbreakable holds on their owners. Ultimately however, even these objects possess only such agency as human actors have invested in them. Can objects possess independent agency? This is the koan I have set myself.

Though my disquieting meditation may never yield conclusive results, it has already proven otherwise productive, as it has led me on a fruitful quest for Weird Tales of a special kind, stories that hover at the very boundary of the Weird—and on either side of that boundary. Jack Spicer wrote that the perfect poetic dictionary would be infinitely small, and I believe that some of the greatest Weird Tales are those in which the Weird elements are as minimal as possible. Such stories often make an asymptotic approach to pure realism. Others begin realistically and peer into The Weird from the other side of that mirror, never quite crossing over but pressing so close their breath frosts the glass. Often such stories contain no supranormal elements whatsoever. And these stories are often the most unsettling of all.

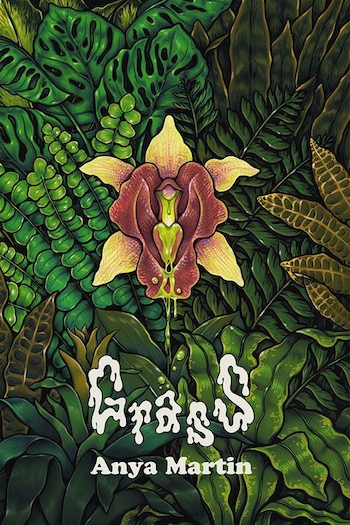

One of the criteria Michael Bukowski and I agreed on for Stories from the Borderland was that every story we chose would have some kind of monster—or at least some kind of creature—that Michael could draw. The sort of stories I am describing here however, rarely offer any such ammunition for Michael’s talents. Around the time this particular line of interest began evolving into the idea for a new series of illustrated essays, Dim Shores Press had just released Anya Martin’s novella Grass, with its eerie and wonderful cover and illustrations by Jeanne D’Angelo. Jeanne’s atmospheric art struck me at once as perfect for the sort of stories toward which I am currently turning…so I pitched her the idea for this second series–hereinafter to be known as Tales from the Crossroads—and she accepted the challenge. What you have been reading thus far is the preamble to our initial installment in this series. We hope you will hang with us for the rest, which comprises everything from this point onward.

One of the criteria Michael Bukowski and I agreed on for Stories from the Borderland was that every story we chose would have some kind of monster—or at least some kind of creature—that Michael could draw. The sort of stories I am describing here however, rarely offer any such ammunition for Michael’s talents. Around the time this particular line of interest began evolving into the idea for a new series of illustrated essays, Dim Shores Press had just released Anya Martin’s novella Grass, with its eerie and wonderful cover and illustrations by Jeanne D’Angelo. Jeanne’s atmospheric art struck me at once as perfect for the sort of stories toward which I am currently turning…so I pitched her the idea for this second series–hereinafter to be known as Tales from the Crossroads—and she accepted the challenge. What you have been reading thus far is the preamble to our initial installment in this series. We hope you will hang with us for the rest, which comprises everything from this point onward.

I have known from the moment of this project’s conception where Tales from the Crossroads would begin, so please allow Jeanne and I to take you now to a certain deserted British strand, and the opening paragraph of “Solid Objects,” one of the more outré stories by Virginia Woolf…an author who wrote several stories and novels that remain outliers to literary convention even today:

“The only thing that moved upon the vast semicircle of the beach was one small black spot. As it came nearer to the ribs and spine of the stranded pilchard boat, it became apparent from a certain tenuity in its blackness that this spot possessed four legs; and moment by moment it became more unmistakable that it was composed of the persons of two young men. Even thus in outline against the sand there was an unmistakable vitality in them…”

The “two young men” who emerge from “one small black spot” in this paragraph are John and Charles. John is the story’s ostensible protagonist. After discovering a vaguely globular lump of colored glass buried in the sand of the beach described above, he progressively loses interest in a promising political career. The glass blob acquires increasing power over John’s thoughts, though not in any explicit way. The lump is neither possessed nor intelligent. It holds no ghostly power, nor does it serve as the fulcrum of any curse. It “does” nothing at any point in the story—at least not in any human sense—yet it acquires an almost absolute hold over its discoverer, a hold whose strength becomes compounded rather than diluted after John finds a second, unrelated object, “a piece of china of the most remarkable shape, as nearly resembling a starfish as anything—shaped, or broken accidentally, into five irregular but unmistakable points.”

The “two young men” who emerge from “one small black spot” in this paragraph are John and Charles. John is the story’s ostensible protagonist. After discovering a vaguely globular lump of colored glass buried in the sand of the beach described above, he progressively loses interest in a promising political career. The glass blob acquires increasing power over John’s thoughts, though not in any explicit way. The lump is neither possessed nor intelligent. It holds no ghostly power, nor does it serve as the fulcrum of any curse. It “does” nothing at any point in the story—at least not in any human sense—yet it acquires an almost absolute hold over its discoverer, a hold whose strength becomes compounded rather than diluted after John finds a second, unrelated object, “a piece of china of the most remarkable shape, as nearly resembling a starfish as anything—shaped, or broken accidentally, into five irregular but unmistakable points.”

After connecting with this second specimen and returning with it to his home—though not without a protracted struggle and neglecting an important meeting in the process—John embarks on a new “career,” obsessively seeking out other unusual fragments and concretions. Around this time the third of the three objects that Woolf describes in detail enters John’s life, “a very remarkable piece of iron…almost identical with the glass in shape, massy and globular, but so cold and heavy, so black and metallic, that it was evidently alien to the earth and had its origin in one of the dead stars or was itself the cinder of a moon,” and he abandons his parliamentary trajectory altogether.

John’s once considerable agency diminishes proportionately as the line of oddments on his mantelpiece lengthens. Human vitality wanes into inertia while the objects “radiate cold.” As John withdraws further from society, Charles—his best friend and apparent political mentor—grows increasingly alienated. Woolf presents the contemplative life into which John and his collection of objects recede as both seductive and horrifying.

John’s once considerable agency diminishes proportionately as the line of oddments on his mantelpiece lengthens. Human vitality wanes into inertia while the objects “radiate cold.” As John withdraws further from society, Charles—his best friend and apparent political mentor—grows increasingly alienated. Woolf presents the contemplative life into which John and his collection of objects recede as both seductive and horrifying.

By the end of the tale, John and his tchotchkes have become what Jane Bennett would describe as a “human/nonhuman assemblage” of “vital materialities” in her 2009 book Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Though Bennett repurposes the concept of “assemblages” from Deleuze and Guattari, she is in her own right a leading thinker of the Nonhuman Turn. Together with Speculative Realism, Object- Oriented Ontology, and several other recent and related reformulations of Western Philosophy, the Nonhuman Turn represents a loose but nonetheless concerted effort to decentralize human agency and bequeath a legitimate intellectual tradition to the rocks or robots or raccoons or roaches or whatever will succeed us in the post- [Anthropocene/ Singularity/ apocalypse/ choose your own poison] world.

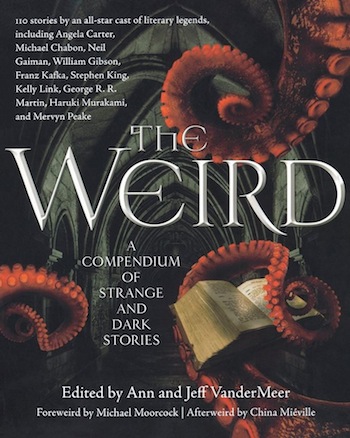

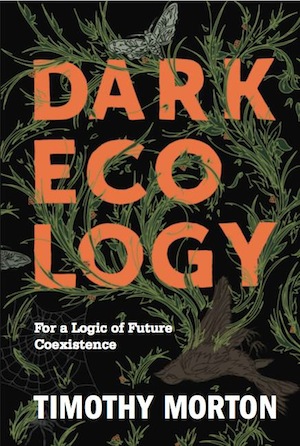

Bennett and Sasha Newell are not the only scholars whose work has shifted the Western intellectual tradition closer to The Weird. In fact, several of the essential figures from philosophy’s esoteric forward edge have engaged directly with Weird Fiction. Notable examples include Eugene Thacker’s three-volume series Horror of Philosophy; Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy by Graham Harman, the founder of Object-Oriented Ontology; Apple Z. Igrek’s important 2011 article “Inanimate Speech from Lovecraft to Žižek“; Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects and Dark Ecology; and most recently Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene.

Bennett and Sasha Newell are not the only scholars whose work has shifted the Western intellectual tradition closer to The Weird. In fact, several of the essential figures from philosophy’s esoteric forward edge have engaged directly with Weird Fiction. Notable examples include Eugene Thacker’s three-volume series Horror of Philosophy; Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy by Graham Harman, the founder of Object-Oriented Ontology; Apple Z. Igrek’s important 2011 article “Inanimate Speech from Lovecraft to Žižek“; Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects and Dark Ecology; and most recently Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene.

One essential text that requires mention here, Reza Negarestani’s 2008 Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials (Anomaly), defies all boundaries between philosophy and fiction, but the engagement between the two realms has otherwise been mostly one-way thus far, with few Weird Fiction authors even taking note of the above works. The unsurprising exception is Jeff “Vanguard” VanderMeer, who has established a literal dialogue not only with Morton, but between their respective oeuvres as well. With Tales from the Crossroads Jeanne and I hope to throw a few more grappling hooks across this divide and pull the two floating continents a little closer together.

One essential text that requires mention here, Reza Negarestani’s 2008 Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials (Anomaly), defies all boundaries between philosophy and fiction, but the engagement between the two realms has otherwise been mostly one-way thus far, with few Weird Fiction authors even taking note of the above works. The unsurprising exception is Jeff “Vanguard” VanderMeer, who has established a literal dialogue not only with Morton, but between their respective oeuvres as well. With Tales from the Crossroads Jeanne and I hope to throw a few more grappling hooks across this divide and pull the two floating continents a little closer together.

In Vibrant Matter, Bennett describes an alternate relationship of objects and human, in which the familiar subject/object division dissolves and agency is distributed and shared. The one passage in which Woolf describes workings of John’s obsession seems to anticipate Bennett’s concept of vital materiality: “Looked at again and again half consciously by a mind thinking of something else, any object mixes itself so profoundly with the stuff of thought that it loses its actual form and recomposes itself a little differently in an ideal shape which haunts the brain when we least expect it.” Though Bennett does not mention Woolf, she ventures at least as close to The Weird as Kafka’s “Die Sorge des Hausvaters,” a tiny tale that Timothy Morton and Slavoj Žižek also cite in their work, and which I think may be the single most essential piece of reading that Weird Fiction has to offer (expect more on that story in our next installment).

In Vibrant Matter, Bennett describes an alternate relationship of objects and human, in which the familiar subject/object division dissolves and agency is distributed and shared. The one passage in which Woolf describes workings of John’s obsession seems to anticipate Bennett’s concept of vital materiality: “Looked at again and again half consciously by a mind thinking of something else, any object mixes itself so profoundly with the stuff of thought that it loses its actual form and recomposes itself a little differently in an ideal shape which haunts the brain when we least expect it.” Though Bennett does not mention Woolf, she ventures at least as close to The Weird as Kafka’s “Die Sorge des Hausvaters,” a tiny tale that Timothy Morton and Slavoj Žižek also cite in their work, and which I think may be the single most essential piece of reading that Weird Fiction has to offer (expect more on that story in our next installment).

The central image of Bennett’s book is her chance meeting with a dead rat, a plastic glove, a bottle cap, some pollen, and a stick atop a storm drain in Baltimore. From this quotidian encounter emerges something greater than these disparate objects, Bennett herself, or even their collective gestalt, just as Ducasse’s depiction of the sewing machine and the umbrella [<< la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d’une machine à coudre et d’un parapluie >> (Les Chants de Maldoror, Canto 6:1)] took center stage in André Breton’s seminal 1924 Manifeste du surréalisme.

The central image of Bennett’s book is her chance meeting with a dead rat, a plastic glove, a bottle cap, some pollen, and a stick atop a storm drain in Baltimore. From this quotidian encounter emerges something greater than these disparate objects, Bennett herself, or even their collective gestalt, just as Ducasse’s depiction of the sewing machine and the umbrella [<< la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d’une machine à coudre et d’un parapluie >> (Les Chants de Maldoror, Canto 6:1)] took center stage in André Breton’s seminal 1924 Manifeste du surréalisme.

I expect that some of you have begun shaking your heads around this point, thinking Kafka, surrealism, OOO, Western Philosophy, and eschatology is too much to pile on one modest little story written just shy of a century ago:. These conjunctions are not coincidence however. Woolf wrote “Solid Objects” in 1918, and it first appeared in the October 1920 issue of The Athenaeum, a year after Kafka published “Hausvaters.” The first Surrealist Manifesto debuted in 1924. That period, especially the decade that began during and immediately followed the end of the First World War, marks the Great Acceleration of Literary Modernism. Woolf, Kafka, and Breton remain among the most influential figures of this time, and as it approaches its own centenary, “Solid Objects” recommends itself to our consideration more than ever.

I expect that some of you have begun shaking your heads around this point, thinking Kafka, surrealism, OOO, Western Philosophy, and eschatology is too much to pile on one modest little story written just shy of a century ago:. These conjunctions are not coincidence however. Woolf wrote “Solid Objects” in 1918, and it first appeared in the October 1920 issue of The Athenaeum, a year after Kafka published “Hausvaters.” The first Surrealist Manifesto debuted in 1924. That period, especially the decade that began during and immediately followed the end of the First World War, marks the Great Acceleration of Literary Modernism. Woolf, Kafka, and Breton remain among the most influential figures of this time, and as it approaches its own centenary, “Solid Objects” recommends itself to our consideration more than ever.

Twentieth century modernism was the literature of a civilization in crisis, a world whose traditions no longer made sense, societies that needed answers to new questions they were not yet able to frame. One hundred years later we find ourselves in an exponentially magnified version of that crisis. The new philosophical turns that decentralize the human in the Western “Humanities” are all efforts to confront the incomprehensibility of global warming and the Anthropocene, the massive dark clouds on humanity’s horizon, their guts lit by flashes of the Singularity, the ultimate age of objects with agency.

Yet if philosophy has already begun to engage with these emergent realities, where is the corresponding literature, our nascent millennium’s answer to modernism? It certainly isn’t the science fiction of last century’s supposed Golden Age—the future as imagined by Robert Heinlein and John W. Campbell now seems as much a fantasy as anything by J.R.R. Tolkien. It appears increasingly unlikely that our species will ever spread to the stars. We’re probably not even going to Mars. We’ll be lucky if some small part of us still clings to the Earth in seven generations.

Yet if philosophy has already begun to engage with these emergent realities, where is the corresponding literature, our nascent millennium’s answer to modernism? It certainly isn’t the science fiction of last century’s supposed Golden Age—the future as imagined by Robert Heinlein and John W. Campbell now seems as much a fantasy as anything by J.R.R. Tolkien. It appears increasingly unlikely that our species will ever spread to the stars. We’re probably not even going to Mars. We’ll be lucky if some small part of us still clings to the Earth in seven generations.

I suggest to you however, that the literature we need has been here all along, that Weird Fiction is the true literature of our time. Both movements trace a common lineage directly through Mary Shelley, Poe, and the Symbolists, but Weird Fiction has long been modernism’s neglected twin, growing slowly in the shadows as its sib flourished, like Wilbur Whateley’s forgotten otherworldly brother, grown monstrous and immense in a boarded-up house—or whatever festered in the abandoned well in “The Colour Out of Space.” It took a century for the world itself to grow visibly weird enough, but at last the world is ready. Or just adequately ruined. It works the same either way.

As a corollary to my argument that Weird Fiction is modernism’s cognate finally come of age, I suggest that we must reexamine early modernism for fiction that also can refine our understanding of The Weird. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer have already made the case for work by Kafka, Alfred Kubin, and Bruno Schulz. With Tales from the Crossroads, Jeanne and I hope to expand the Weird Canon further, making the case for the inclusion of various short stories from literature’s mainstream since the late nineteenth century. We think “Solid Objects,” this tale of obsession, ghosts, dead stars, strange and powerful objects, and misplaced agency, is a deeply weird story and an excellent place to start.

As a corollary to my argument that Weird Fiction is modernism’s cognate finally come of age, I suggest that we must reexamine early modernism for fiction that also can refine our understanding of The Weird. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer have already made the case for work by Kafka, Alfred Kubin, and Bruno Schulz. With Tales from the Crossroads, Jeanne and I hope to expand the Weird Canon further, making the case for the inclusion of various short stories from literature’s mainstream since the late nineteenth century. We think “Solid Objects,” this tale of obsession, ghosts, dead stars, strange and powerful objects, and misplaced agency, is a deeply weird story and an excellent place to start.

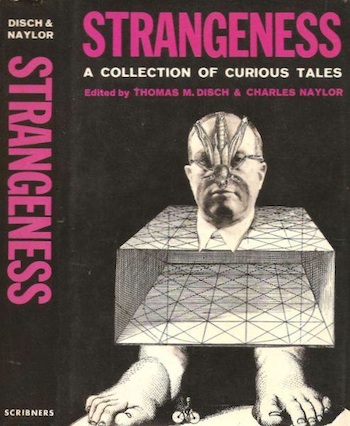

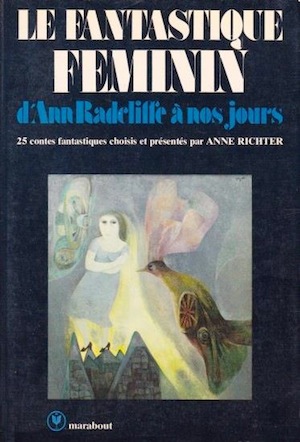

Nor are we the first to recognize the unsettling nature of this tale. In 1997, shortly after it was reprinted in a posthumous collection of Woolf’s stories entitled A Haunted House, Thomas Disch included “Solid Objects” alongside works by Shirley Jackson, Italo Calvino, M. John Harrison, and others in his anthology Strangeness: A Collection of Curious Tales. And that same year, Anne Richter, a leading figure in the Belgian school of The Weird, published a French translation in a wonderful volume of stories by female authors: Le fantastique féminin d’Ann Racliffe à nos jours. That collection also included a French version of Hortense Calisher’s “Heartburn,” which Michael and I recently covered in Stories from the Borderland, as well as Daphne DuMaurier’s classic Weird novella “The Birds,” and several interesting stories that have never appeared in English. Richter described “Solid Objects” as “one of those tiny and demanding paintings, a meditation on the startling metamorphoses of the real” (un de ces tableaux menus et exigeants, une rêverie sur les surprenantes mêtamorphoses du reel), while Disch identified it as an example of what he called the “Naturalized Gothic.” These are powerful endorsements that place Woolf’s story firmly within a tradition that runs from Radcliffe, Poe, and the nineteenth century gothic into the modern Weird, strange, and uncanny.

Nor are we the first to recognize the unsettling nature of this tale. In 1997, shortly after it was reprinted in a posthumous collection of Woolf’s stories entitled A Haunted House, Thomas Disch included “Solid Objects” alongside works by Shirley Jackson, Italo Calvino, M. John Harrison, and others in his anthology Strangeness: A Collection of Curious Tales. And that same year, Anne Richter, a leading figure in the Belgian school of The Weird, published a French translation in a wonderful volume of stories by female authors: Le fantastique féminin d’Ann Racliffe à nos jours. That collection also included a French version of Hortense Calisher’s “Heartburn,” which Michael and I recently covered in Stories from the Borderland, as well as Daphne DuMaurier’s classic Weird novella “The Birds,” and several interesting stories that have never appeared in English. Richter described “Solid Objects” as “one of those tiny and demanding paintings, a meditation on the startling metamorphoses of the real” (un de ces tableaux menus et exigeants, une rêverie sur les surprenantes mêtamorphoses du reel), while Disch identified it as an example of what he called the “Naturalized Gothic.” These are powerful endorsements that place Woolf’s story firmly within a tradition that runs from Radcliffe, Poe, and the nineteenth century gothic into the modern Weird, strange, and uncanny.

“Solid Objects” also presents us with an almost ideal entry point for opening a discussion of OOO, Speculative Realism, and the Nonhuman Turn in the context of Weird Fiction–from the creative side, which is an explicit goal of this new series.

“Solid Objects” also presents us with an almost ideal entry point for opening a discussion of OOO, Speculative Realism, and the Nonhuman Turn in the context of Weird Fiction–from the creative side, which is an explicit goal of this new series.

That said, I remain of two minds regarding the new movements—or “turns”—in philosophy. As an author, exploring the possibilities they offer for writing Weird Fiction intrigues me immensely. At the same time, I find their central emphasis on decentralizing humanity problematic and disturbing. True, this is the very basis of “cosmic horror,” but this approach can also be used—and has been—to weaponize The Weird and place it in the service of oppression. When we say that human life does not matter, it is even easier to dismiss the suffering of any subgroup as insignificant. Bennett provides a particularly good example: her attempts to frame her approach to material agency in the political sphere, though intellectually valid, feel almost abhorrent to me, even dangerous. In this regard, she seems to me like John, a ghost in academia while fascists are in motion right outside. Both remind me of the millions who chose not to vote in recent elections, or who followed some shiny headline while fascist demagogues and populist movements flourished.

Perhaps I am being unfair to Bennett and her peers however. The way she describes assemblages for instance, makes them useful for describing the monsters that have arisen from the intersection of the electorate and the economy with white nationalism vitalized via currents of redistributed agency. Timothy Morton especially seems plugged in to our current reality. His insistence on identifying his primary model of the hyperobject as “global warming,” rather than the euphemistic “climate change,” is laudable. Our train has taken a very wrong turn, and not only is there no light at the end of the tunnel, we are quickly running out of tunnel. At least Bennett, Morton, et al. acknowledge that reality. This mode of “realism” melds well with The Weird.

Perhaps I am being unfair to Bennett and her peers however. The way she describes assemblages for instance, makes them useful for describing the monsters that have arisen from the intersection of the electorate and the economy with white nationalism vitalized via currents of redistributed agency. Timothy Morton especially seems plugged in to our current reality. His insistence on identifying his primary model of the hyperobject as “global warming,” rather than the euphemistic “climate change,” is laudable. Our train has taken a very wrong turn, and not only is there no light at the end of the tunnel, we are quickly running out of tunnel. At least Bennett, Morton, et al. acknowledge that reality. This mode of “realism” melds well with The Weird.

Meanwhile Jeff VanderMeer discusses the ways hyperobjects haunt us from their other-dimensional lairs. Yet he also recognizes that all objects haunt us in their ways. As they acquire more agency we become more like ghosts. The more important they become to us, the more inert we grow in turn, like John:

“The things that haunt us in this age are often the things we care about or have some connection to, no matter how slight, and if they are also the things that matter we either need to become cynics or hedonists and change the things we care about so we don’t care when they’re destroyed, so the hauntings cannot affect us…”

As fascism, fundamentalism, and populism acquire agency over us all, people become the things that haunt us; even in life they become monsters and ghosts. Our strength follows them, given over to fear, to panic. We cling to things as we fear losing those about whom we care. The vibrancy of matter comes in part from the life it drains from us. As our own political power slips away, the final lines of “Solid Objects” echo with a deafening weight:

As fascism, fundamentalism, and populism acquire agency over us all, people become the things that haunt us; even in life they become monsters and ghosts. Our strength follows them, given over to fear, to panic. We cling to things as we fear losing those about whom we care. The vibrancy of matter comes in part from the life it drains from us. As our own political power slips away, the final lines of “Solid Objects” echo with a deafening weight:

“What was the truth of it, John?” asked Charles suddenly, turning and facing him. “What made you give it up like that all in a second?”

“I’ve not given it up,” John replied.

“But you’ve not the ghost of a chance now,” said Charles roughly.

Pondering the future has always meant thinking of our individual selves as ghosts, but as we awaken into a world where our entire species has only “a ghost of a chance,” a haunted literature becomes our intellectual home. Stories that speak to these truths achieve a solidity beyond flesh, and we have many more to share with you. Jeanne D’Angelo and I invite you to join us on further journeys through the blighted zero point where our neglected past intersects an unthinkable future in forthcoming installments of Tales from the Crossroads.

Leave a Reply