Nothing is what it seems to be chez Tiptree, least of all, Tiptree. Don’t think for a moment that knowing their legal name was Alice Sheldon, AKA Raccoona, AKA Alli, leaves you on any solid ground. Our subject is a psychologist who helped forge the modern CIA from the disjointed remnants of the OSS—and who was still leaking classified information in their first novel over a decade after they supposedly left The Agency. They must have been a regular terror at the old “tell me three things about yourself, one of which is a lie” game. Consider how well a CIA psychologist could fuck with your mind. After they pinched a pseudonym from a venerable UK manufacturer of marmalades they found they could fuck with more minds than ever through the medium of fiction.

Nothing is what it seems to be chez Tiptree, least of all, Tiptree. Don’t think for a moment that knowing their legal name was Alice Sheldon, AKA Raccoona, AKA Alli, leaves you on any solid ground. Our subject is a psychologist who helped forge the modern CIA from the disjointed remnants of the OSS—and who was still leaking classified information in their first novel over a decade after they supposedly left The Agency. They must have been a regular terror at the old “tell me three things about yourself, one of which is a lie” game. Consider how well a CIA psychologist could fuck with your mind. After they pinched a pseudonym from a venerable UK manufacturer of marmalades they found they could fuck with more minds than ever through the medium of fiction.

What a game it was in those days to see Tiptree lay their cards out in such a way the bloviating big shots of science fiction’s boys’ club had no choice but to rally round the imposture. Tiptree wrote too dangerously and just too damn well for the world’s Silverbergs and Ellisons to allow them to be anything other than another swinging dick at the sausage party. Only once the boys had got behind Mr. Tiptree the tough guy and set their bets on the table they saw Alice Sheldon’s trickery laid bare and discovered they’d been had.

Of course we speak here of Tiptree the science fiction writer, while our bailiwick is The Weird. Can we claim Tiptree as our own? Well I would swear this chimera swims with one fin in our waters, oh yes, yes I would. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer already went as far when they included “The Psychologist Who Wouldn’t Do Awful Things to Rats” in their benchmark anthology The Weird, describing Tiptree as writing “within or at the edges of recognizable traditions of weird fiction.” I would argue a large part of Tiptree’s oeuvre is tinged with cosmic horror, in their short fiction especially, but also their first novel, Up the Walls of the World. The latter also deserves note as one of the first literary treatments not only of the CIA’s psychic research programs (still classified at the time), but more importantly of the all-too-real nightmare of female genital mutilation (we’re talking 1978 here, folks).

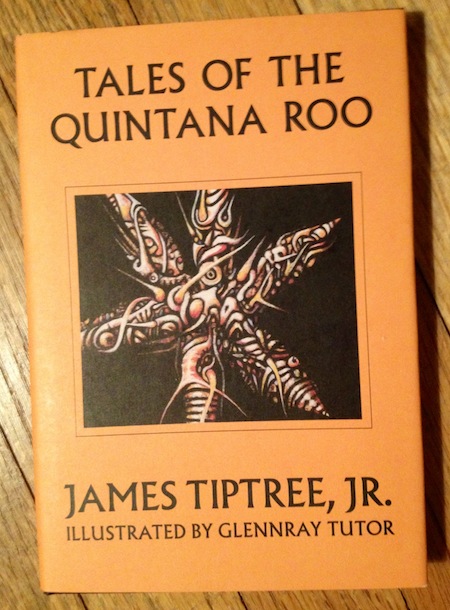

In the twilight hours of their life Tiptree penned a hat trick of stories set along the Yucatan peninsula, which Arkham House later gathered in a slim handsome volume under the title Tales of the Quintana Roo. The collection scored a World Fantasy Award in 1987, though posthumously alas. Of the three tales in Tales, the first two are more conventionally supernatural, though the first, “What Came Ashore at Lirios,” is an erotic genderbending corker of the very highest order which leaves the primary narrator’s own gender and sexuality ambiguous as well—if the reader has the subtlety to notice without assigning defaults.

In the twilight hours of their life Tiptree penned a hat trick of stories set along the Yucatan peninsula, which Arkham House later gathered in a slim handsome volume under the title Tales of the Quintana Roo. The collection scored a World Fantasy Award in 1987, though posthumously alas. Of the three tales in Tales, the first two are more conventionally supernatural, though the first, “What Came Ashore at Lirios,” is an erotic genderbending corker of the very highest order which leaves the primary narrator’s own gender and sexuality ambiguous as well—if the reader has the subtlety to notice without assigning defaults.

Each of the stories in Tales is a “told-to tale,” a tradition well worn though not worn out even a millennium ago, and one which still works well in the modern Weird (cf. Ralph Cram’s “The Dead Valley”). Tiptree’s narrator appears to be the same throughout—appears to be Tiptree throughout, in fact—but we have already established that with Tiptree identity is mutable and nothing represents reliably. Thus when the reader arrives at the volume’s final tale, “Beyond the Dead Reef,” the narrator warns in the very first line: “My informant was, of course, spectacularly unreliable.” Here we have Tiptree the Agency wraith, beckoning us to follow with the very threat of skullfuckery—come on in, the water’s fine—yet never telling us what’s under the surface till we’re in way over our heads.

Though beyond and even because of its nested nature the narrative is conventional, even classical, the story itself is a delight, replete with detail and dread and masterfully employing the writer’s power over the reader’s gaze in much the same way for which I have praised Poe in the past. Tiptree knows what the brain sees is not what the eye takes in. Thus narrator follows narrator and reader follows diver, till suddenly no one knows where they are any longer, other than lost and alone. Via the unreliable guide of a woman who is not a woman yet neither a fish, Tiptree leads the reader though a dangerous and contaminated literary ecology into a confrontation with a monstrous and fragmentary femininity. In the end what lies beyond the dead reef is Tiptree’s own hidden lair, and the true self there revealed soon disintegrates into impossible parts: “hungry life by death begot,” as the story’s short poetic coda describes.

“Beyond the Dead Reef” deserves recognition also as an early use of The Weird to address ecology, and the dead reef is thus a precursor of Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X. Ecology and cosmic horror is a combination and concern that manifested early in Tiptree’s work, as in their 1969 story “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain.”

“Beyond the Dead Reef” deserves recognition also as an early use of The Weird to address ecology, and the dead reef is thus a precursor of Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X. Ecology and cosmic horror is a combination and concern that manifested early in Tiptree’s work, as in their 1969 story “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain.”

James Tiptree, Jr or Alice Sheldon, man or woman, woman or fish? In the end you can only follow them so far before you run out of air. You will never be able to dive as deep or stay down as long. Not if you ever plan to return as other than a floater. Your guide in this case is…spectacularly unreliable. And there I shall leave you…

Until next week at least, when Stories From the Borderland concludes on January 6. Now follow me to artist Michael Bukowski’s blog, where you can view his illustration for Tiptree’s tale.

Speaking for myself I will say this collaborative project with Michael has been an absolute blast, and we plan to go out with a bang, with an über creepy story of a multi-legged monster from a world-renowned author…a story which probably none of you have read. Can you guess the title? I am offering a signed copy of the terribly rare chapbook of “The Bad Outer Space” to the first person who can. Thus far no one has guessed a single of our selections in advance.

No, next week is neither “Mimic” or “Who Goes There?”

Michael and I are considering a second series of Stories From the Borderland, so if you would like us to continue, please let us know.