The previous installment of Stories From the Borderland examined “The Cactus,” a tale by Mildred Johnson, an enigmatic female author who published only two known stories, both in Weird Tales. This week the author of our featured selection is another mysterious byline from Weird Tales. Allison V. Harding was not only the magazine’s most prolific contributing female author: she was its tenth most prolific contributor altogether, well ahead of many of the magazine’s better known male authors such as Ray Bradbury or Frank Belknap Long. And though we know much more about Harding than Mildred Johnson, she remains in many ways even more enigmatic. She may in fact be The Unique Magazine’s most enigmatic author of all, and its most enduring mystery.

The previous installment of Stories From the Borderland examined “The Cactus,” a tale by Mildred Johnson, an enigmatic female author who published only two known stories, both in Weird Tales. This week the author of our featured selection is another mysterious byline from Weird Tales. Allison V. Harding was not only the magazine’s most prolific contributing female author: she was its tenth most prolific contributor altogether, well ahead of many of the magazine’s better known male authors such as Ray Bradbury or Frank Belknap Long. And though we know much more about Harding than Mildred Johnson, she remains in many ways even more enigmatic. She may in fact be The Unique Magazine’s most enigmatic author of all, and its most enduring mystery.

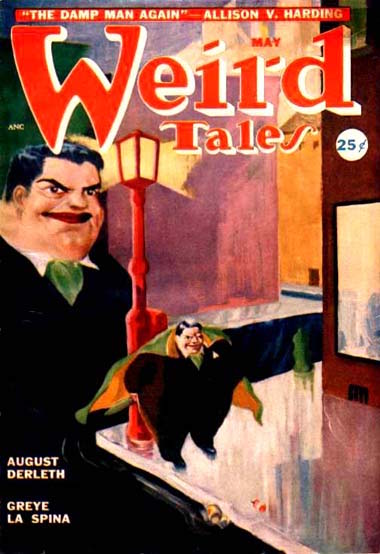

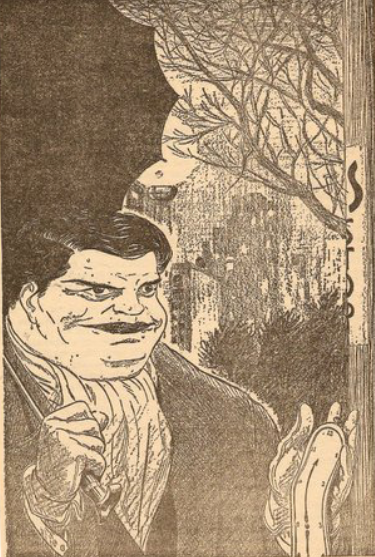

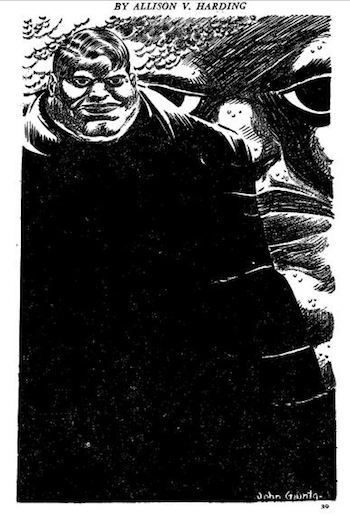

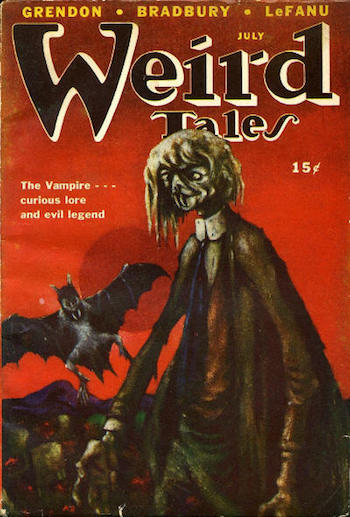

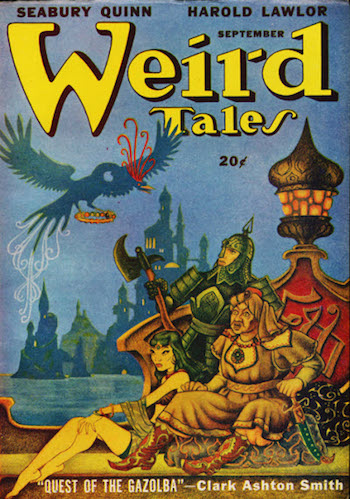

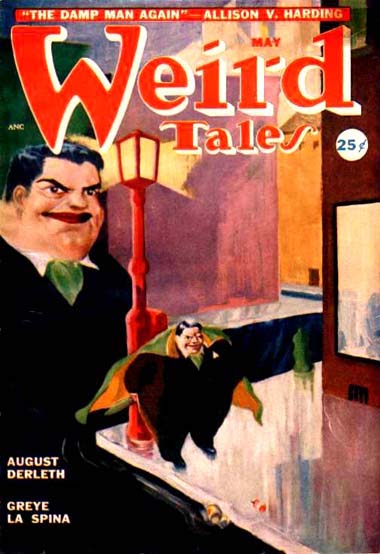

To the extent that Harding is remembered today, it is primarily for a single story, “The Damp Man,” and its titular antagonist. First published in the July 1947 issue of Weird Tales, “The Damp Man” proved popular enough to spawn two sequels: “The Damp Man Returns” in September 1947—just three months after the original—and “The Damp Man Again” in May 1949 [please take a moment to appreciate the subtlety of those titles]. The final installment made the cover, with a creepy depiction of the spongy antagonist himself by artist John Giunta.

“The Damp Man” is essentially the story of a woman terrorized by a stalker in 1940s Manhattan…and about how there was legally nothing she could do about it. Beneath the surface of this pulp tale lurks a disturbing statement about the lives of American women. Stalking laws—even the term “stalker” itself in its current connotation—did not enter common parlance until the late twentieth century. Linda Mallory, the Damp Man’s young victim, quickly discovers that society has stacked the deck in favor of her stalker.

“The Damp Man” is essentially the story of a woman terrorized by a stalker in 1940s Manhattan…and about how there was legally nothing she could do about it. Beneath the surface of this pulp tale lurks a disturbing statement about the lives of American women. Stalking laws—even the term “stalker” itself in its current connotation—did not enter common parlance until the late twentieth century. Linda Mallory, the Damp Man’s young victim, quickly discovers that society has stacked the deck in favor of her stalker.

Although Mallory is the story’s focal character, a male voice overlays her tale. The opening paragraphs introduce us first to Gazette reporter George Pelgrim, also young but already jaded, and chafing at being assigned to cover a women’s swimming championship, which he considers a “comedown” from his editor. Despite his smoldering resentment, Pelgrim makes a halfhearted effort to fulfill his professional responsibilities and arranges a brief interview with Miss Mallory, the winner of the competition. This is where things begin to get weird. Here as well begin SPOILERS for those who have not read the story—or played the Call of Cthulhu RPG “Damp Man: Swim Meet of Doom.”

Circumstances throw Linda and George together and a mutual affection inevitably develops. For a time they manage to evade the ambling moist monstrosity whose real name is revealed to be Lother Remsdorf, Jr…but only for a time. Eventually the Damp Man simply kidnaps Ms. Mallory. In an interesting twist for a story of that era, she escapes unaided. Women in the pulps typically required rescue by men. The overall amount of detail devoted to Linda Mallory’s character, and the degree of agency ascribed to her in the story—despite her partial reliance on Pelgrim—are unusual for both the medium and the time, and despite the choice of a male narrator, these aspects speak strongly of female authorship. This is important, as new questions have arisen regarding Harding’s identity.

Circumstances throw Linda and George together and a mutual affection inevitably develops. For a time they manage to evade the ambling moist monstrosity whose real name is revealed to be Lother Remsdorf, Jr…but only for a time. Eventually the Damp Man simply kidnaps Ms. Mallory. In an interesting twist for a story of that era, she escapes unaided. Women in the pulps typically required rescue by men. The overall amount of detail devoted to Linda Mallory’s character, and the degree of agency ascribed to her in the story—despite her partial reliance on Pelgrim—are unusual for both the medium and the time, and despite the choice of a male narrator, these aspects speak strongly of female authorship. This is important, as new questions have arisen regarding Harding’s identity.

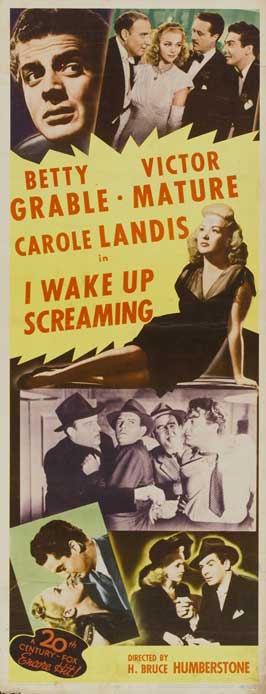

Artist/writer Terence E. Hanley has explored the enigma of Allison V. Harding further than anyone else. His research is impressive, and his conclusions are insightful, as when he suggests her signature story shows the influence of the classic 1941 film noir I Wake Up Screaming, with the character of the Damp Man himself drawing somewhat on the film’s sinister, obsessive, and heavyset detective Ed Cornell, portrayed by Laird Cregar. IWUS is one of the first dozen films of the original noir era, so if Hanley is correct, “The Damp Man” represents one of the earliest hybrids of The Weird and Noir, though ultimately this is true regardless of any cinematic influence. With its combination of an urban setting, a cynical investigator, an expressionistically grotesque and unnatural nemesis, and its bleak depiction of society, “The Damp Man” incorporates many key elements of noir. Hanley’s primary thesis, however, is that the author we know as Allison V. Harding may not be a woman at all.

Exactly who was Allison V. Harding, and what do we know about her? If not for Sam Moskowitz we might know nothing beyond her bibliography, as he was one of the last to examine the magazine’s payment records before their alleged destruction, and he later revealed [to Robert Weinberg?] that the cashed checks for Allison V. Harding’s stories were made out to one Jean Milligan. Because the checks were sent to a prominent New York City law firm, Moskowitz identified Milligan—incorrectly, it seems—as an attorney during Harding’s publishing years (she was more likely a legal clerk or secretary or perhaps just a client of the firm). The clincher seems to be that Milligan’s future husband, author [Charles] Lamont Buchanan, served from September 1942 until September 1949 as the associate editor and art director of Weird Tales under Dorothy McIlwraith, the final editor of the magazine’s original incarnation. Buchanan is perhaps best remembered today for recruiting artist Lee Brown Coye into the Weird Tales stable.

Exactly who was Allison V. Harding, and what do we know about her? If not for Sam Moskowitz we might know nothing beyond her bibliography, as he was one of the last to examine the magazine’s payment records before their alleged destruction, and he later revealed [to Robert Weinberg?] that the cashed checks for Allison V. Harding’s stories were made out to one Jean Milligan. Because the checks were sent to a prominent New York City law firm, Moskowitz identified Milligan—incorrectly, it seems—as an attorney during Harding’s publishing years (she was more likely a legal clerk or secretary or perhaps just a client of the firm). The clincher seems to be that Milligan’s future husband, author [Charles] Lamont Buchanan, served from September 1942 until September 1949 as the associate editor and art director of Weird Tales under Dorothy McIlwraith, the final editor of the magazine’s original incarnation. Buchanan is perhaps best remembered today for recruiting artist Lee Brown Coye into the Weird Tales stable.

Based on this connection, Hanley concludes that “Allison V. Harding” was actually Lamont Buchanan, not Jean Milligan. Jean did not take the Buchanan surname until they married in 1952, at least a year after the last of the Harding stories saw print).

Hanley’s conclusion is plausible. While Buchanan was a known author credited with the texts of sixteen illustrated books on sports and historical topics, Jean Milligan is practically a cipher, with much more information available about her parents and sisters than her. If she wrote outside the Harding nom de plume no one has ever found the evidence (other than a one time use of the name Alice B. Harcraft for the story “Ride the El to Doom,” which reappeared later under the Harding byline). Lamont Buchanan himself ceased publishing in 1956, perhaps because the sort of illustrated books in which he specialized declined in popularity, and after a lone reference to him in his father’s 1962 obituary, husband and wife both disappear permanently from public life in the way that only the very wealthy and the very poor can do.

Back at Tellers of Weird Tales things start to get weird on another level altogether, as Hanley goes on in later blog posts to suggest an alternative identity for the tenth most prolific contributor to Weird Tales: author J.D. Salinger. Hanley’s suggestion is based on two things. Firstly, though they may have met earlier, both Buchanan and Salinger attended Columbia University School of General Studies, its night course program, though Buchanan is listed in the directory for 1938 and Salinger attended in 1939. Considering Salinger’s fixation on F. Scott Fitzgerald, it seems natural that an old money student bearing the surname Buchanan would have engaged his interest. It is interesting to note that Jack Kerouac also enrolled in Columbia a year later but does not seem to have crossed paths with either Salinger or Buchanan—not surprising given that Kerouac was a working class football player on an athletic scholarship, while Buchanan and Salinger were older and came from higher socioeconomic strata. A decade later Salinger moved into an apartment less than two blocks from Lamont and Jean in Sutton Place, suggesting their friendship continued throughout the ‘40s, or at least that they moved in the same social circles.

Back at Tellers of Weird Tales things start to get weird on another level altogether, as Hanley goes on in later blog posts to suggest an alternative identity for the tenth most prolific contributor to Weird Tales: author J.D. Salinger. Hanley’s suggestion is based on two things. Firstly, though they may have met earlier, both Buchanan and Salinger attended Columbia University School of General Studies, its night course program, though Buchanan is listed in the directory for 1938 and Salinger attended in 1939. Considering Salinger’s fixation on F. Scott Fitzgerald, it seems natural that an old money student bearing the surname Buchanan would have engaged his interest. It is interesting to note that Jack Kerouac also enrolled in Columbia a year later but does not seem to have crossed paths with either Salinger or Buchanan—not surprising given that Kerouac was a working class football player on an athletic scholarship, while Buchanan and Salinger were older and came from higher socioeconomic strata. A decade later Salinger moved into an apartment less than two blocks from Lamont and Jean in Sutton Place, suggesting their friendship continued throughout the ‘40s, or at least that they moved in the same social circles.

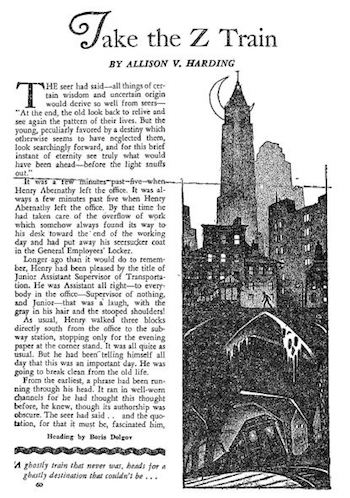

The second factor is the pronounced similarity in language and tone between the Allison V. Harding’s penultimate story, “Take the Z Train” from the May 1950 issue of Weird Tales, and The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger’s famous novel debuted on July 16, 1951, barely six months after “Scope,” the final tale to bear the Harding byline. If Salinger did indeed maintain his friendship with his friend and neighbor Buchanan by that time, it is likely that Jean and Lamont may have seen galleys of Catcher.

The second factor is the pronounced similarity in language and tone between the Allison V. Harding’s penultimate story, “Take the Z Train” from the May 1950 issue of Weird Tales, and The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger’s famous novel debuted on July 16, 1951, barely six months after “Scope,” the final tale to bear the Harding byline. If Salinger did indeed maintain his friendship with his friend and neighbor Buchanan by that time, it is likely that Jean and Lamont may have seen galleys of Catcher.

Although Hanley quickly retracts this assertion, he deserves credit for making the connection between Salinger and Allison V. Harding, a connection I do not believe has been noted elsewhere. Neither Lamont nor Jean are mentioned in any of the major Salinger biographies however. Hanley’s sole source for the Buchanan-Salinger collection is a 2012 article by veteran journalist Noel Young:

Young’s topic is a recently rediscovered 1941 interview with Salinger conducted by Shirley Ardman, who was a freshman at Columbia that year, also studying journalism. According to Young, who interviewed Ardman prior to her own demise, it was Lamont Buchanan who introduced her to Salinger. Though Young makes no mention of Buchanan’s Weird Tales tenure, he casually drops this bombshell: “Later, Shirley was to suggest that Lamont was at least in part the model for Holden Caulfield, the central figure in The Catcher in the Rye.” Only Hanley seems to have made the connection between Salinger’s Buchanan and the obscure author and pulp magazine editor.

Young’s topic is a recently rediscovered 1941 interview with Salinger conducted by Shirley Ardman, who was a freshman at Columbia that year, also studying journalism. According to Young, who interviewed Ardman prior to her own demise, it was Lamont Buchanan who introduced her to Salinger. Though Young makes no mention of Buchanan’s Weird Tales tenure, he casually drops this bombshell: “Later, Shirley was to suggest that Lamont was at least in part the model for Holden Caulfield, the central figure in The Catcher in the Rye.” Only Hanley seems to have made the connection between Salinger’s Buchanan and the obscure author and pulp magazine editor.

This surprising connection suggests some interesting connections. Let us take as our starting point the revelation that Lamont Buchanan = Holden Caulfield. Maybe, maybe only partially, but if Ardman was correct, then one of the most famous protagonists in Twentieth Century American fiction inherited the literary DNA of a man who served as associate editor of Weird Tales throughout most of its last full decade.

Remember that Hanley has made the case that Lamont Buchanan was actually Allison V. Harding. Although Harding relied on male protagonists and points of view, in “The Damp Man” at least she presented a genuine female perspective along with specific insights into midcentury women’s lives, such as the experience of living in an all-women’s rooming house, of which there were nearly sixty in Manhattan during that era, the most famous of which was the legendary Barbizon, located only a few blocks from Jean and Lamont’s homes on the Upper East Side. I will posit instead that “Allison V. Harding” was the shared pseudonym of a husband and wife writing team, an early multiple-use name or collective pseudonym such as Alan Smithee or Luther Blissett, employed in much the same way that Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore were already collaborating under such pen names as Lewis Padgett and Lawrence O’Donnell. Which of them wrote what, and how much, is beyond telling now. It may be that Lamont developed the stories around Jean’s ideas, or vice versa, or that one or the other of them was responsible for more of Harding’s output in later years.

The suggestion that Buchanan alone assumed the Harding name to create filler for Weird Tales begs several questions: first of all, if he alone wrote as Harding, why would he deceive his own boss? Alternatively, if Dorothy McIlwraith was in on such a secret, why would she send the checks to Jean care of a third party? This makes much more sense if Harding was either Jean by herself or a collaboration. The necessity of avoiding the impression of nepotism would itself have demanded a pseudonym. Moreover, both Jean and Lamont came from wealthy families. However Lamont’s family felt about his employment with the pulps, Jean’s family might have been even less accepting.

The suggestion that Buchanan alone assumed the Harding name to create filler for Weird Tales begs several questions: first of all, if he alone wrote as Harding, why would he deceive his own boss? Alternatively, if Dorothy McIlwraith was in on such a secret, why would she send the checks to Jean care of a third party? This makes much more sense if Harding was either Jean by herself or a collaboration. The necessity of avoiding the impression of nepotism would itself have demanded a pseudonym. Moreover, both Jean and Lamont came from wealthy families. However Lamont’s family felt about his employment with the pulps, Jean’s family might have been even less accepting.

Although none of the Harding stories I have read come anywhere close to passing the Bechdel Test, if the name concealed a collaboration, “The Damp Man,” with its particularly feminine elements, is the smoking gun. We don’t know [yet] if Jean was a competitive swimmer or lived in an all women’s rooming house, but we do know Lamont studied journalism, which means the character of George Pelgrim incorporates some of his personality as well. If Lamont Buchanan = George Pelgrim AND Lamont Buchanan = Holden Caulfield, then George Pelgrim = Holden Caulfield, n’est-ce pas? Really not so fanciful a conclusion when one remembers Holden’s fanciful career goal, so central to the very title of The Catcher in the Rye, of serving as a sort of protector or guardian of the innocent. A wild idea perhaps…but stick with me here—things at Stories From the Borderland are about to get even wilder. I have discussed here before the unexpected connections that arise when pulp stories receive a deep reading, but this story drizzles into territory I never foresaw.

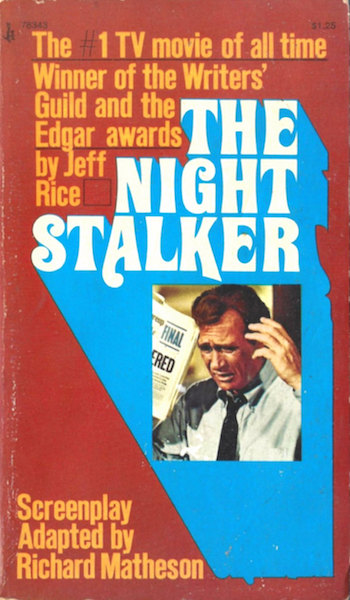

Reading “The Damp Man” for this project quickly called to mind Eugene Tooms, the recurring elastic liver-eater from The X-Files, and from Tooms my thoughts leapt at once to The Night Stalker, the primary inspiration for The X-Files. While Scully and Mulder work for the FBI, Carl Kolchak, The Night Stalker’s protagonist is a reporter like George Pelgrim.

Reading “The Damp Man” for this project quickly called to mind Eugene Tooms, the recurring elastic liver-eater from The X-Files, and from Tooms my thoughts leapt at once to The Night Stalker, the primary inspiration for The X-Files. While Scully and Mulder work for the FBI, Carl Kolchak, The Night Stalker’s protagonist is a reporter like George Pelgrim.

Harding’s story reminded me specifically of The Night Stalker’s second television pilot, The Night Strangler (1973). The latter featured as its antagonist one Dr. Richard Malcolm, a Civil War era surgeon still alive and lurking in Seattle’s underground city, emerging every 21 years to murder young women and extract their still warm pituitary glands in order to concoct his elixir of immortality. The character of Tooms most likely owes a great deal to Dr. Malcolm. Could either or both owe some debt to “The Damp Man”?

Richard Matheson wrote the scripts for both pilots. Had Matheson read “The Damp Man”? He began publishing in 1950, just three years after the original Damp Man story appeared in Weird Tales, and almost exactly one year after “The Damp Man Again.” Within three years Matheson was publishing in Weird Tales itself, so he was clearly familiar with the magazine. Did a bit of George Pelgrim creep into Carl Kolchak as Matheson reimagined Jeff Rice’s character for television? If so, then Kolchak is not only partly Pelgrim, but part Lamont Buchanan as well.

And if Kolchak is partly George Pelgrim is partly Lamont Buchanan…then Fox Mulder is as well.

Consider this then: Lamont Buchanan may have been [in part] the model for Holden Caulfield. He was almost certainly the model [in part] for George Pelgrim. If George Pelgrim influenced Richard Matheson [or Jeff Rice?] in his development of Carl Kolchak, and The Night Stalker series inspired The X-Files, then could Fox Mulder be…the Catcher in the Rye? The idea makes a surprising amount of sense. It is really quite easy to envision poor broken yet brilliant Agent Mulder, tortured by his sister’s childhood abduction, as an adult version of Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. Which gives us then: Lamont Buchanan = Holden Caulfield/George Pelgrim = Carl Kolchak = Fox Mulder = the Catcher in the Rye?

Consider this then: Lamont Buchanan may have been [in part] the model for Holden Caulfield. He was almost certainly the model [in part] for George Pelgrim. If George Pelgrim influenced Richard Matheson [or Jeff Rice?] in his development of Carl Kolchak, and The Night Stalker series inspired The X-Files, then could Fox Mulder be…the Catcher in the Rye? The idea makes a surprising amount of sense. It is really quite easy to envision poor broken yet brilliant Agent Mulder, tortured by his sister’s childhood abduction, as an adult version of Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. Which gives us then: Lamont Buchanan = Holden Caulfield/George Pelgrim = Carl Kolchak = Fox Mulder = the Catcher in the Rye?

A final connection deserves mention, though I am certain this one is pure coincidence: The X-Files was shot primarily in and around Vancouver, British Columbia, and “The Damp Man” features the only antagonist I can recall who is killed by Canada. Well, perhaps not killed, not if he returns.

Jean Milligan attended the Connecticut College for Women for two years from fall 1936 to spring 1938 before dropping out, perhaps to help her father after her mother’s sudden death in 1938. Is she one of the young women in this photo of the freshmen class from the 1937 yearbook? Unfortunately the names are not listed, but this may be the first known photo of Allison V. Harding.

The search for Allison V. Harding took this episode of Stories From the Borderland down an unexpected and seemingly bottomless research k-hole. I am especially grateful to Anya Martin, who dove deep and returned with many new and crucial elements details from the story. We ended up logging quite a few hours during our investigation of the strange case of Allison V. Harding, and we are far from finished, so expect further announcements.

In the meantime, please follow this link to Michael Bukowski’s blog, where you can view his illustration of Lother Remsdorf, Jr., the Damp Man himself. Be warned that Michael draws all creatures and characters other than deities naked, so Lother appears unclothed there. This is appropriately creepy really, given the Damp Man’s ultimate designs on Linda Mallory. Be glad Lother never chose you for a mate.

Two more bloggers take on the mystery of Allison V. Harding:

Lesser Known Writers: Allison V. Harding

Silvia Moreno-Garcia: “Summer of Unknown Writers: Dorothy Quick and Allison V. Harding

Leave a Reply