I was lucky enough to grow up only a few blocks from my hometown’s public library. By the time I was eight or nine and allowed to cross Middlebrook’s busy main street on my own, I became as frequent a visitor there as my father. My family was so familiar to the regular librarians that they never had to look up our number when we checked out books. By the Sixth Grade I had graduated to the adult sections, and I became a habitué of that one aisle just past the entrance on the right, where all the books on one side were marked with blue cloth tags depicting a pipe-smoking mustachioed sleuth, while those opposite bore white squares emblazoned with a red rocketship at the nucleus of a lithium atom.

I was lucky enough to grow up only a few blocks from my hometown’s public library. By the time I was eight or nine and allowed to cross Middlebrook’s busy main street on my own, I became as frequent a visitor there as my father. My family was so familiar to the regular librarians that they never had to look up our number when we checked out books. By the Sixth Grade I had graduated to the adult sections, and I became a habitué of that one aisle just past the entrance on the right, where all the books on one side were marked with blue cloth tags depicting a pipe-smoking mustachioed sleuth, while those opposite bore white squares emblazoned with a red rocketship at the nucleus of a lithium atom.

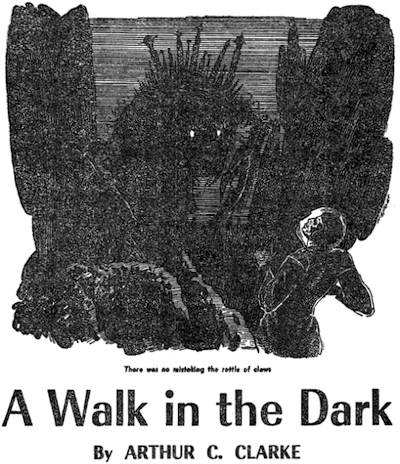

I plundered both sides of that aisle, never forgetting the blue flags sometimes concealed genuine horror amidst the drawing room mysteries (Hitch—or more properly, Robert Arthur, Jr.—you were a good and true friend), but the volumes flying the flag of the rocket were my focus. I sometimes spent as much as an hour making my selections, and once an author found my favor, I would mine her/his oeuvre as far as the collection permitted. For a period in junior high I dedicated myself to Arthur C. Clarke, reading several novels and at least four entire collections. Oddly, the only one of Clarke’s short stories I can recall with any clarity—other than “The Sentinel,” which I have since taught—is “A Walk in the Dark” (audio version here).

Given my tastes, this is perhaps not so odd. And approaching Clarke through this one tale provides an interesting alternative to the usual biographical emphasis on his penchant for orbital calculations and similar trappings of the hard science school of science fiction. Although Clarke wrote little horror per se, many of his major works blurred the line between sensawunda and cosmic horror, especially “The Sentinel,” 2001, and Rendezvous With Rama.

This consideration has led me to an interesting conjecture. I have written elsewhere about how The Weird possesses a history equal to or greater than most of the established genres, yet it has only recently begun to differentiate itself. For decades much of the best Weird Fiction buried itself in science fiction, fantasy, and conventional horror. The Weird only really began to emerge as a discrete phenomenon around the turn of the last century. My conversations with Michael Kelly and others who take a big picture view of The Weird have emphasized its essential indefinability, despite its considerable longevity. Could it be the postwar division of genre fiction in the Anglophone world actually stifled or delayed the emergence of The Weird, that The Weird had thus to await the Small Press Boom that coincided more or less with the fin de siècle? This is far too large a topic to tackle here, but my wheels are spinning, and “A Walk in the Dark” seems an excellent example of the way many great Weird Tales from much of the last century are hidden within other genres, an idea that has become an ongoing theme of this series.

This consideration has led me to an interesting conjecture. I have written elsewhere about how The Weird possesses a history equal to or greater than most of the established genres, yet it has only recently begun to differentiate itself. For decades much of the best Weird Fiction buried itself in science fiction, fantasy, and conventional horror. The Weird only really began to emerge as a discrete phenomenon around the turn of the last century. My conversations with Michael Kelly and others who take a big picture view of The Weird have emphasized its essential indefinability, despite its considerable longevity. Could it be the postwar division of genre fiction in the Anglophone world actually stifled or delayed the emergence of The Weird, that The Weird had thus to await the Small Press Boom that coincided more or less with the fin de siècle? This is far too large a topic to tackle here, but my wheels are spinning, and “A Walk in the Dark” seems an excellent example of the way many great Weird Tales from much of the last century are hidden within other genres, an idea that has become an ongoing theme of this series.

Though Clarke hailed from the U.K., I see hints in his tale of two classic American short stories, Jack London’s “To Build a Fire” and Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” I have repeatedly mentioned the former as one of the finest examples of cosmic horror without any supernatural element, and the latter is pocket master class in establishing dread.

As simple as these stories are however, Clarke’s tale is simpler yet. On a planet at the edge of the galaxy, Armstrong must travel four miles in almost absolute dark. His vehicle has quit on him, his flashlight has also failed, the planet is at the galaxy’s edge so its sky is short on stars. Armstrong decides he can make it safely though. The planet is uninhabited, barren. It supports no known life forms to harass him. The road is distinct beneath his boots. All he needs to do is follow it without a major fall in order to reach his destination and his departing flight. A simplified version of the hard science scenario: reason overcomes the atavistic fear of the dark.

Clarke is essentially telling a campfire tale, and its motifs are likely as old as the most ancient conjunction of campfires and tales. I am sure if I knew my Stith Thompson better I could identify the precise motifs and explore their other known occurrences. Haunted forests. Mountain passes. All this has happened before, right here on Earth, but none of it means a wit to Armstrong. He has crisscrossed the galaxy multiple times…and seen strange and terrifying things. And his struggle is his alone. No space dog accompanies him, no love triangle distracts him. He desires only to reach the spaceport before the Canopus departs so he can leave this dismal world forever

Clarke is essentially telling a campfire tale, and its motifs are likely as old as the most ancient conjunction of campfires and tales. I am sure if I knew my Stith Thompson better I could identify the precise motifs and explore their other known occurrences. Haunted forests. Mountain passes. All this has happened before, right here on Earth, but none of it means a wit to Armstrong. He has crisscrossed the galaxy multiple times…and seen strange and terrifying things. And his struggle is his alone. No space dog accompanies him, no love triangle distracts him. He desires only to reach the spaceport before the Canopus departs so he can leave this dismal world forever

Port Sanderson, the name of his destination, is almost certainly an Easter egg, a reference to Ivan T. Sanderson, the early New Jersey cryptologist and exotic animal wrangler who provides a bridge between Charles Fort and Loren Coleman. By the time Clarke wrote “A Walk in the Dark,” Sanderson had already achieved some degree of fame–or infamy–thanks to his claimed encounter with a kongamato in Africa. The kongamato is reputed to be a large bat-like creature, a sort of Congolese Jersey Devil (Sanderson’s account of the kongamato attack also bears an interesting resemblance to the H.G. Wells story “In the Avu Observatory,” one of our earliest weird cryptozoological tales). If Clarke was name-checking Sanderson, as seems likely, he is hinting this may be a cryptid story. Of course, “Cryptid” is a more recent coinage—terms like “unknown creature” and “hidden animal” had more currency in 1950—and they fit the story even better.

This possibility is quickly validated via Armstrong’s flashback to an old clerk’s story of the time something followed him from Carver’s Pass in the darkness, keeping always just beyond the beam of his flashlight, its presence distinguished only by the “chitinous” clicking sounds it made. This passage recalls the flashback in “To Build a Fire,” wherein the old-timer on Sulphur Creek offers advice to the story’s unnamed chechaquo protagonist. Like the chechaquo, Armstrong scoffed at the old-timer’s tale. Only that tale doesn’t seem so funny now, alone in the dark with four miles to go, and Carver’s Pass still between him and Port Sanderson.

This possibility is quickly validated via Armstrong’s flashback to an old clerk’s story of the time something followed him from Carver’s Pass in the darkness, keeping always just beyond the beam of his flashlight, its presence distinguished only by the “chitinous” clicking sounds it made. This passage recalls the flashback in “To Build a Fire,” wherein the old-timer on Sulphur Creek offers advice to the story’s unnamed chechaquo protagonist. Like the chechaquo, Armstrong scoffed at the old-timer’s tale. Only that tale doesn’t seem so funny now, alone in the dark with four miles to go, and Carver’s Pass still between him and Port Sanderson.

Armstrong quickly shoves the old clerk’s campfire tale out of his mind. The planet is lifeless, his only enemies in the darkness are time and irrational fear. Except…the plant-beings of Xantil Major…except the life forms of Trantor Beta…except the massive rock out beyond Carver’s Pass, that massive rock near the entrance to a mysterious tunnel, larger than all the rest, that massive rock worn down as if “used as an enormous whetstone.” Except he doesn’t have a working flashlight like the old clerk.

Armstrong skirts the pass without incident. From there on all his dread becomes focused behind. He expects each moment to hear the chitinous clicks of giant claws at his back. But the sound never comes. What a relief the lights of Port Sanderson provide when poor Armstrong at last rounds the final bend and sees them a mere few hundred yards ahead. What a relief they provide…don’t they?

Don’t they?

I will never forget finishing this tale forty years ago, and having to remind myself it was daytime, and that I was still on Earth.

Now hurry on over to Michael Bukowski’s blog [link: https://yog-blogsoth.blogspot.com/2016/04/the-thing-in-dark.html] to see just what might be following you around on your next walk in the dark.

Stories From the Borderland returns on April 13, when we reach out to bring you one of the weirdest amusement park stories of all time. Keep your hands and feet inside the vehicle at all times—the management is not responsible for any accidents!