A horror story about children can be especially disturbing—Something Wicked This Way Comes, IT, “The Specialist’s Hat.” Throwing adults into unnatural peril is one thing—they at least can grasp their options, draw on support, choose to make sacrifices. Children are at once incredibly vulnerable yet charged with potential, so we fear more for them and the immense possibility of their futures than we do for the intrepid polar explorer, the graying antiquary, or the other interchangeable narrators of so many weird and gothic tales. How cruel the author who chooses children as protagonists in a narrative of weirdness and monsters.

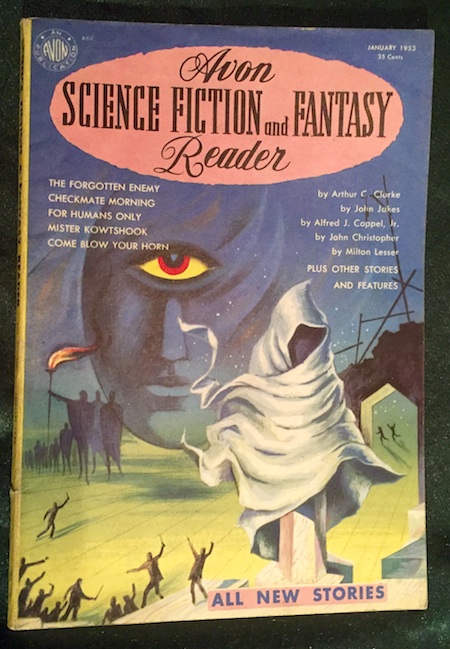

“The Shed” is Weird Horror done much like Charles Schulz’ Peanuts comics, with adults kept mostly off screen, their voices the sound of muted trumpets. Considering Peanuts debuted on 2.Oct.1950, fewer than three years before “The Shed” first appeared in print (in the Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader of January 1953), this might even be more than a coincidence, unlikely as it is that we ever shall know.

Though Evans came to writing with enthusiasm, he came to it late in life, and his entire literary career spanned a mere five years. His work is comparable to Bradbury’s in both style and content, and they actually collaborated on at least one story. “The Shed” was probably Evans’ most successful tale, managing at least half a dozen reprints before slipping into oblivion after 1974 along with the rest of his oeuvre.

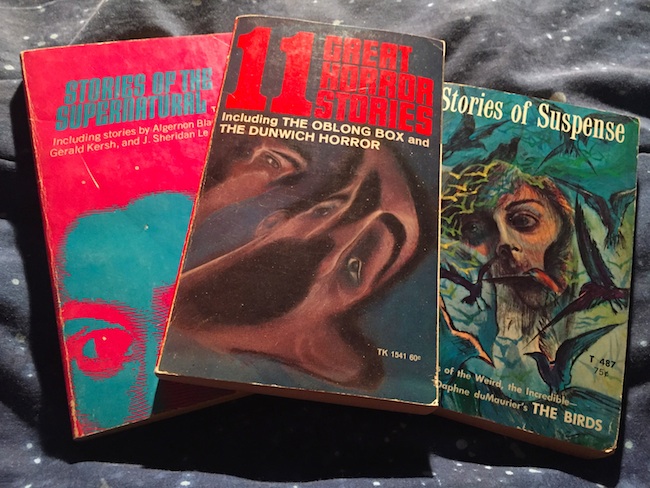

I first encountered this story back in 1970, in a little Scholastic paperback titled 11 Great Horror Tales, the same book in which I first encountered Lovecraft. It was one of a series of similar Scholastic anthologies edited by the inimitable Betty M. Owen. I expect mine was not the only young mind warped by these volumes, which featured stories by du Maurier, Blackwood, and Gerald Kersh as well as Lovecraft and Evans.

Good ol’ Betty M. Owen knew her audience, I have to give her that. Imagine young Scooter Nicolay reading this tale, seven years old and having just discovered the Hardy Boys, the Hulk, and “The Dunwich Horror.” Here I am paying tribute to her editorial skills forty-five years later.

Thus we come to the opening of “The Shed,” by E. Everett Evans: “The three boys stood in the dim, dust-moted corner of The Shed, gazing curiously at that mysterious Shadow.” What chance can “three boys” stand against the “Shadow,” an entity so puissant it has already achieved a status demanding capitalization before the curtains are drawn? This tells us right off the monster is unique, and therefore an unknown, a creature without prior referents, like Zontar, Ghidrah, or Kong.

“The Shed” is set nearly a century ago, and appears to draw heavily on the author’s own memories of childhood, a time when working class children like Cuddy, Hutch, and Stub might play freely around railroad yards and slaughterhouses. In this it has always evoked my late father’s tales of growing up in Jersey City, or Jean Shepherd’s narratives of youthful shenanigans in the pre-WWII steel mill Midwest with Schwartz, Flick, and Bruner (stories that later provided the basis for the perennial holiday film A Christmas Story). Shepherd was another of my 1970 discoveries, thanks to the transistor radio I got for Christmas. His show on WOR, though no longer the late night Benzedrine Beat Era madness immortalized at the end of Kerouac’s On the Road, was still airing late enough to be well past my bedtime. Fortunately with the aid of a plastic earpiece screwed deep into my waxy little ear I could enjoy it surreptitiously, huddled under the covers. All I know of storytelling is rooted in those stolen hours.

My own childhood was free range enough. We rode our bikes along the train tracks to other towns, played on an abandoned sewage treatment plant, rowed down oily streams in rusted iron bins or on huge chunks of Styrofoam, played around industrial waste. The playground behind my family’s church was built over radioactive landfill from the Manhattan Project, which came from a Marine base on the edge of town. We saw strange things. My friends and cousins and I probably would have been at home in The Shed, though how we might have dealt with the Shadow, I do not know. [From here on there be spoilers. I am sorry my friends, I take pains to avoid them, but this time I have no choice.] Cuddy, Hutch, and Stub know how to deal with it though. They belong to an even hardier era of American youth, when young boys thought nothing of borrowing a diseased cow from a slaughterhouse.

At the end of “The Shed” the boys have defeated the Shadow, though not all of them survive. Beloved pets do not fare so well either. And once the Shadow has dissolved in its final technicolor paroxysm…the boys return to their acrobatics in The Shed:

“Slowly he [Hutch] straightened. His eyes seemed to refocus sanely. Then he grinned.

“Dibs on the high trap!” He raced toward the center of The Shed.”

“Dibs on the long rope!” Cuddy was only momentarily behind him.”

The boys continue their play as if nothing happened. PTSD lasts an eyeblink. I confess this ending never bothered me when I read it as a kid, nor the many times I reread this story over the years since, at least not until these last few years after I had begun to write fiction in earnest and maybe read just that much deeper. What does that say about the story? What does it say about America? What does it say about young Scooter? What does it say about me now?

A horror story about children can be especially disturbing.

Go now to Michael Bukowski’s blog, yogblogsoth, where you can see his half of this week’s Stories From the Borderland: the child-devouring “Shadow” itself. And be sure to visit both our blogs again on Dec. 16, when our topic will be a perfect little masterpiece by a master of the short story, but one that never seems to be recognized as weird–perhaps because it won one of science fiction’s major awards, and has thus remained hidden in plain sight through this odd sort of mimicry.